John Abduljaami (1941-2017)

John Abduljaami, (born 1941, Shawnee, OK) renowned self-taught Oakland California wood sculptor; carves found wood, sculpting with axe, chisel, and saw. He polychromes these with house-paint. His sculptures are powerful and spirited works, mostly depicting animals and portraits, generally larger than life. He quit high school to join the navy; as a jet mechanic he was stationed in Japan for two years, and afterwards moved to San Francisco with his family. John served four years for robbery in the late 1960's, during which he changed his name and joined the nation of Islam. He is now non-denominational, and believes God will take of everything in the end. John received a certificate of valor for his heroic rescue of victims in the Loma Prieta earthquake, pulling survivors from the still crumbling Cypress freeway, using his ladders to reach them. He lost his house which was next to the collapsed structure, which had previously been documented and designated as an art historical site for preservation, by The Smithsonian Institution.

The Dancers

Oil on Canvas

19x22x15 inches

1984

Not signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Charles Alston (1907–1977)

Charles Alston was born in Charlotte, North Carolina in 1907 to the Reverend Primus Priss Alston and Anna Elizabeth Miller Alston. Alston’s father, who nicknamed him Spinky, died when Alston was three. His mother subsequently married Harry Bearden, uncle of Romare Bearden. In 1915, the family moved to Harlem, but Alston continued to spend summers in North Carolina until he was fifteen. As a teenager, Alston painted and sculpted from life, mastering an academic-realist style, and in 1925, he was offered a scholarship to the Yale School of Fine Arts but decided to attend Columbia University instead. Alston received his BA with a concentration in fine arts in 1929 and continued on for a master’s degree at Columbia University Teachers College, where he became increasingly interested in African art and aesthetics. While in graduate school, Alston taught at the Utopia Children’s House, where he became mentor to a young Jacob Lawrence. He received his MA in 1931.

Having finished graduate school in the midst of the Great Depression, Alston remained in Harlem, one of the city’s hardest-hit communities. in 1934, he co-founded the Harlem Art Workshop. When the Workshop needed more space soon after, he found it at 306 West 141st Street. Aided by funding from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), “306” (as it was known) became a center for the most creative minds in Harlem. Regulars included Bearden, Lawrence, Augusta Savage, Richard Wright, Robert Blackburn, Countee Cullen, Ralph Ellison, and Gwendolyn Knight. In 1935, Alston became the first black supervisor in the Federal Art Project when he was assigned to direct the WPA’s Harlem Hospital murals. The paintings he designed—influenced by the work of Mexican muralists, jazz music, and the prevailing social realism of the 1930s—were approved by the Federal Art Project but rejected by the hospital’s administration for what they saw as an excess of subject matter relating to African Americans. After protests and extensive press coverage, the muralists were allowed to proceed. In 1936, two of the works were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). Two Rosenwald Fellowships at the end of the decade enabled Alston to travel throughout the south and to work with Hale Woodruff at Atlanta University. During World War II, Alston worked as an artist for the Office of War Information, served in the US Army, and was also a member of the board of directors for the National Mural Society. In 1944, he attended the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn for a year, and in 1949, he and Woodruff created murals for the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance building in Los Angeles. Entitled Negro in California History, the project comprised two works—Exploration and Colonization (1537-1850) by Alston and Settlement and Development (1850-1949) by Woodruff.

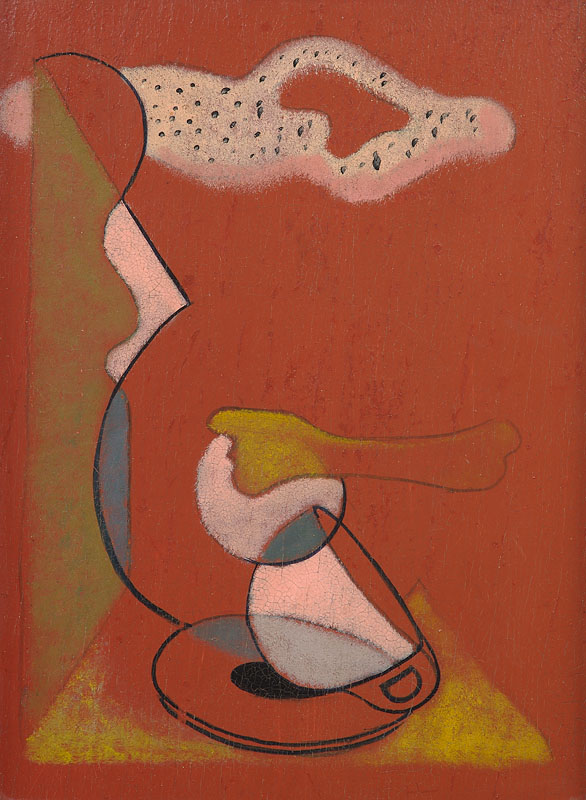

Alston began creating abstract paintings in the 1950s, but he never abandoned figural representation. Instead, he would shift between the two modes of painting, depending on what he believed was best for a given subject. In 1950, he entered one of his new, abstract works in the competitive exhibition American Painting Today at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It won the purchase prize, and the museum acquired it. Many of Alston’s abstract works from this decade were inspired by African art, but unlike several of his his abstract expressionist contemporaries whose passion for American Indian, Pacific, and African art was connected to a modernist search for an imagined “primitive” impulse, Alston’s paintings were created through an intimate knowledge of African aesthetics. In Alston’s work, the African influence is part of a dialogue between past and present, one that finds modernism in tradition and vice-versa.

From his early days at the Utopia Children’s House in 1930 until his death in 1977, Alston remained an influential teacher and a committed activist. He taught at the Art Students League, MoMA, and City College. In 1963, he co-founded the Spiral Group (along with Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, Hale Woodruff, and others), which sought to contribute to the Civil Rights movement through the visual arts in part by increasing gallery and museum representation for black artists. In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Alston as a trustee of the Kennedy Center, and in 1970, Alston became a member of the New York City Arts Commission. In 1975, Columbia University Teacher’s College, which once barred Alston from a required life-drawing course because the models were white, honored him with its first Distinguished Alumni Award.

Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Alston

Harlem at Midnight

Oil on canvas

28x36 inches

1948

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

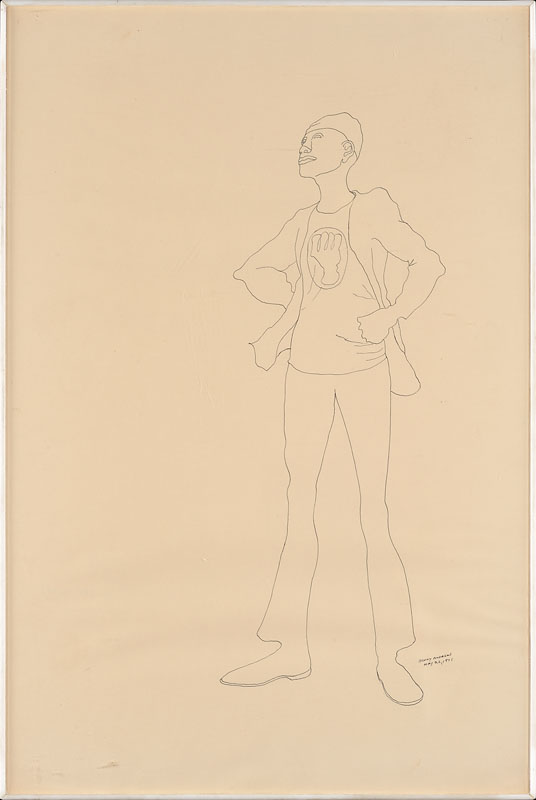

Benny Andrews (1930-2006)

Benny Andrews was born into a family of ten on November 13, 1930 in small community called Plainview, Georgia. His mother Viola was very strict on her beliefs, and constantly promoted education, religion and most importantly, freedom of expression. George, Andrew’s father, also taught the same beliefs to his children. George, internationally known as the "Dot Man," was a self-taught artist, and produced many illustrative drawings that influenced Andrews.

Although the importance of education was stressed, Andrews’s number of absences accumulated due to the days he was needed on the field. Andrews graduated in 1948,from Burney Street High School in Madison, making him the first in his family to graduate high school. Andrews attended Fort Valley College on a two-year scholarship. There was only one art program offered at the institution, due to poor grades and the end of his scholarship Andrews left and joined the U.S. Air force in 1950.

Afterwards, the G.I. Bill of Rights afforded him training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where he received his BFA. His first New York solo show was in 1962. From 1968 to 1997, Andrews taught at Queens College, City University of New York and created a prison arts program that became a model for the nation.

After graduating from the Art Institute of Chicago he received the John Hay Whitney Fellowship for 1965-1966 and a CAPS award from the New York State Council on the arts in 1971[1] the same the same year he created the painting No More Games, a noted work which is about the plight of black artists and an iconic reflection of his emerging social justice work in the art world.[2]

In 1969, Andrews co-founded the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) an organization that protested the 'Harlem on my Mind' exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. They protested the fact that no African-Americans were involved in organizing the show and it contained no art only photo reproductions and copies of newspaper articles about Harlem.. The BECC then persuaded the Whitney museum to launch a similar exhibition of African American Artists, but later boycotted that show as well for similar reasons.[3] In 2006, he traveled to the Gulf Coast to work on an art project with children displaced by Hurricane Katrina.[4]

He was the director of visual arts for the National Endowment for the Arts from 1982 to 1984.

Benny Andrews was a figural painter in the expressionist style who painted a diverse range of themes of suffering and injustice, including The Holocaust, Native American forced migrations, and most recently, Hurricane Katrina. He began his own style of painting in the 1960s that developed parallel to the flourishing collage moment.[1] Other influences on his work include Surrealism and Southern folk art. His work hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago, the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York City, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Reflecting his minimalist style, Andrews was known to say that he was not interested in how much he could paint but how little. He incorporated his sparing use of geometrical forms to convey broader messages about the people and places he depicted. Gabriel Tenabe describes his drawing as "delicate, subtle, and intimate... draw(ing) from his past private life in Georgia and his social life in New York." Christian imagery is juxtaposed with sensibilities of humanism calling out false religion, false democracy, sexism and militarism that have birthed a failed society.[1]

Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benny_Andrews

The Bird

Oil on board

26x19 inches

1964

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

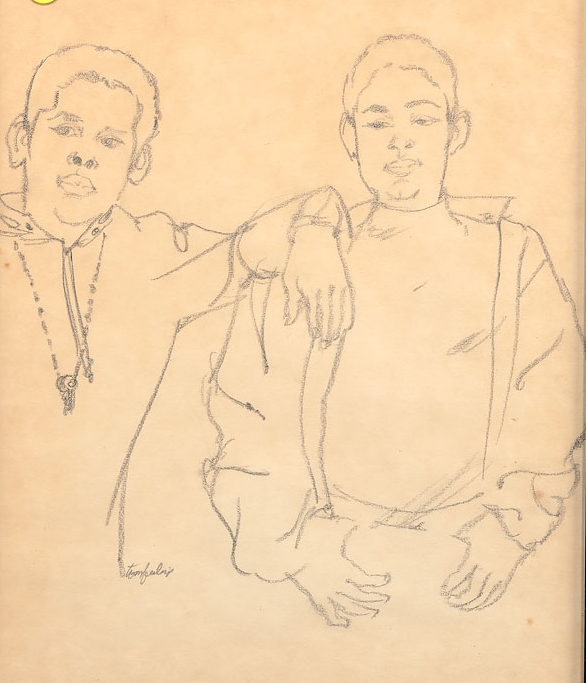

Black Power

Pencil on paper

18x12 inches

1971

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

William Artis (1917-1977)

William Ellisworth Artis (February 2, 1914 – April 3, 1977)[1][2] was an African-American sculptor.

Born in Washington, North Carolina, he moved to New York as a teen in 1927. He was a pupil of Augusta Savage and exhibited with the Harmon Foundation. He studied at the Art Students League of New York and Syracuse University, where he worked with Ivan Meštrović. From 1941–45, he served in the U.S. Army during World War II.[1]

He later taught at Nebraska Teachers College in Kearney (today Chadron State College[3]), where from 1956 to 1966 he was Professor of Ceramics, and at Mankato State College as Professor of Art until 1975.

Link to bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Artis

Classroom resources: http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artist/?id=27550

Head of a Boy

Terracotta

11 1/2 inches high

c. 1930

Not signed (plaque on bust says W. Artis)

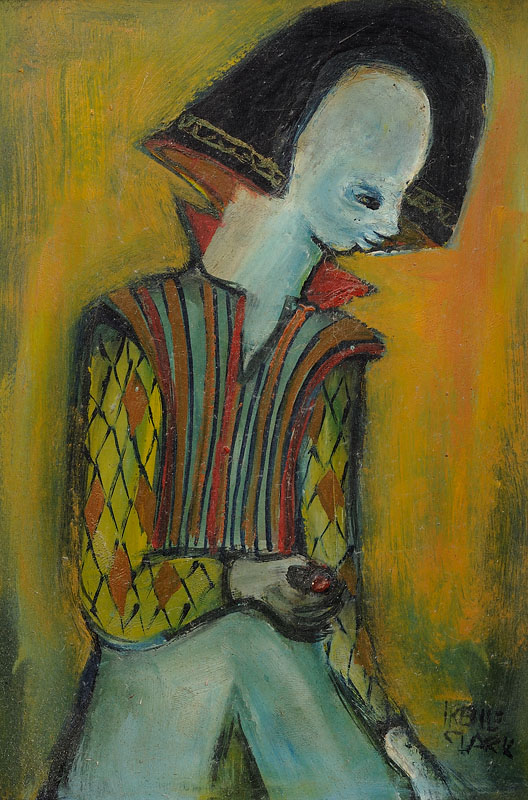

Roland Ayers (1932-1914)

Roland Ayers was born on July 2, 1932, the only child of Alice and Lorenzo Ayers, and grew up in the Germantown district of Philadelphia. Ayers served in the US Army (stationed in Germany) before studying at the Philadelphia College of Art (currently University of the Arts). He graduated with a BFA in Art Education, 1954. He traveled Europe 1966-67, spending time in Amsterdam and Greece in particular. During this period, he drifted away from painting to focus on linear figurative drawings of a surreal nature. His return home inaugurated the artist’s most prolific and inspired period (1968-1975). Shortly before his second major trip abroad in 1971-72 to West Africa, Ayers began to focus on African themes, and African American figures populated his work almost exclusively.

In spite of Ayers’ travel and exploration of the world, he gravitated back to his beloved Germantown, a place he endowed with mythological qualities in his work and literature. His auto-biographical writing focuses on the importance of place during his childhood. Ayers’ journals meticulously document the ethnic and cultural make-up of Germantown, and tell a compelling story of class marginalization that brought together poor families despite racial differences. The distinctive look and design of Germantown inform Ayers’ visual vocabulary. It is a setting with distinctive Gothic Revival architecture and haunting natural beauty. These characteristics are translated and recur in the artist’s imagery.

During his childhood, one of the only books in the Ayers household was an illustrated Bible. The images within had a profound effect on the themes and subjects that would appear in his adult work. Figures in an Ayers’ drawing often seem trapped in a narrative of loss and redemption. Powerful women loom large in the drawings: they suggest the female role models his journals record in early life. The drawings can sometimes convey a strong sense of conflict, and at other times, harmony. Nature and architecture seem to have an antagonistic relationship that is, ironically, symbiotic.

A critical turning point in the artist’s career came in 1971 when he was included in the extremely controversial Whitney Museum show, Contemporary Black Artists in America. The exhibition gave Ayers an international audience and served as a calling card for introductions he would soon make in Europe.

Ayers is a particularly compelling figure in a period when black artists struggled with the idea of authenticity. A questioned often asked was “Is your work too black, or not black enough?” Abstractionists were considered by some peers to be sell-outs, frauds or worse. Figurative* work was accused of being either sentimental or politically radical depending on the critical source. Ayers made the choice early on to be a figurative artist, but considered his work devoid of political content.

Organizations such as Chicago’ s Afri-Cobrain the late 1960‘s asserted that the only true black art of any relevance must depict the black man and woman. A martial agenda of this nature trivialized the work in Ayers’ view. A devotee of Eastern religions, Ayers sought to explore deeper subjects of a less topical nature, thereby stepping outside political discourse. This is not to suggest that he was a man who rejected the physical world. He was profoundly interested in awareness of our environment, and how it relates to self-awareness. He often spoke of universality and timelessness as qualities to strive for in his art.

Roland Ayers: In His Own Words

…A person who refuses or is unable to give into the general consensus of his or her society may retain the capacity to see the world in a vastly different way. That person, in addition to having his or her personal construct of the world — and we all have that — usually has also retained the capacity to be more aware of that unique way of seeing as well as to use it.

… (my work) oftentimes reveals my fragmented consciousness: full of dream states and visions concerning one-world-togetherness: bits and pieces of primal religiosity that point to Europe as much as it does Africa; Afro-American cultural imagery, all presented up-front with an optimistic facade. However, there is another side: part of the dream as nightmare, simmering terrors underneath or just around the corner, ominous dark skies, lonely figures, fragmentary, confused thoughts on being black in the dark, cavernous belly of America, curses and cries in the night. I cannot always decide which story the finished product illuminates: an upbeat optimist or a frustrated, lonely pessimist. Or both at once: Gemini-like, each facing his own way, one foot planted in the West, the other in the East.

The diverse range of American scenes and people are depicted in various media using a figurative style that reflects the dignity of the lives of those he portrayed while serving his commitment to social change.

Link to bio: http://www.terenchin.com/2012/09/11/roland-ayers-b-1932/

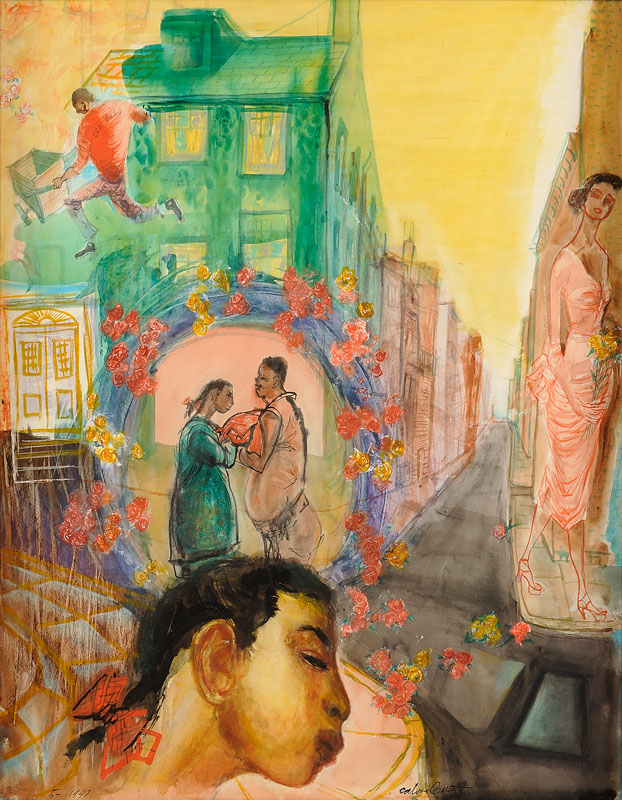

Persistent Rumors

Mixed media, colored pencil. pen and ink with wash

20-29 inches

1963

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Edward M. Bannister (1828-1901)

Edward Mitchell Bannister (ca. 1828 – January 9, 1901) was a Black Canadian-American Tonalist painter. Like other Tonalists, his style and predominantly pastoral subject matter were drawn from his admiration for Millet and the French Barbizon School.

Bannister was born in St. Andrews, New Brunswick and moved to New England in the late 1840s, where he remained for the rest of his life. While Bannister was well known in the artistic community of his adopted home of Providence, Rhode Island and admired within the wider East Coast art world (he won a bronze medal for his large oil "Under the Oaks" at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial), he was largely forgotten for almost a century for a complexity of reasons, principally connected with racial prejudice.

With the ascendency of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1970s, his work was again celebrated and collected. In 1978, Rhode Island College dedicated its Art Gallery in Bannister's name with the exhibition: "Four From Providence ~ Alston, Bannister, Jennings & Prophet". This event was attended and commented on by numerous notable political figures of the time, and supported by the Rhode Island Committee for Humanities and the Rhode Island Historical Society. Events like this, across the entire cultural landscape, have ensured that his artwork and life will not be again forgotten.

Although primarily known for his idealised landscapes and seascapes, Bannister also executed portraits, biblical and mythological scenes, and genre scenes. An intellectual autodidact, his tastes in literature were typical of an educated Victorianpainter, including Spenser, Virgil, Ruskin and Tennyson, from whose works much of his iconography can be traced.

Bannister died of a heart attack in 1901 while attending a prayer meeting at his church, Elmwood Avenue Free Baptist Church. He is buried in the North Burial Ground in Providence.

Link to full bio:

Untitled (Landscape with Girl and Cows)

Oil on board

4 1/4x8 1/2 inches

1881

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

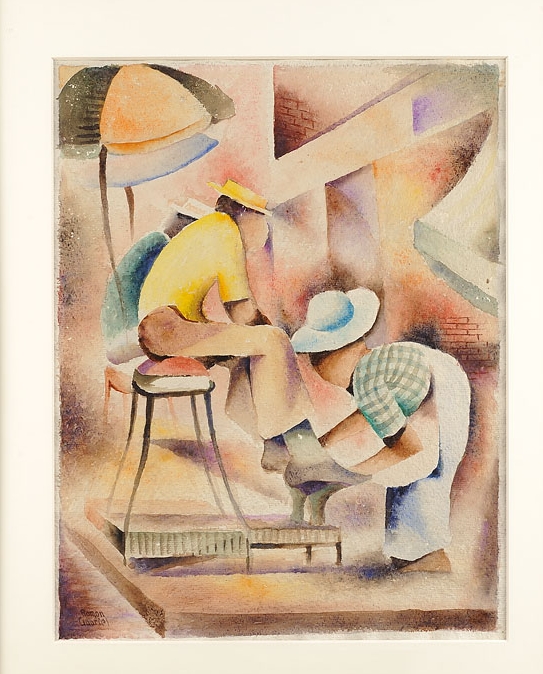

Henry Bannarn (1910-1955)

Henry Wilmer "Mike" Bannarn (July 17, 1910 – September 20, 1965) was an African-American artist, best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance period. He is known for his work in sculpture and as a character artist in the various paint mediums, Conté crayon, pastel, and free-form sketch.

He was born in Wetumka, Hughes County, Oklahoma, on July 17, 1910. When he was still a child, the family moved to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where he discovered his talent for art. He studied at the Minneapolis School of Arts (now known as the Minneapolis College of Art and Design).

He worked as a Works Progress Administration artist for the Federal Art Project and taught art at the Harlem Community Art Center in New York City, where he was a noted contemporary, friend and partner of another famous African-American artist, Charles Alston, with whom he ran the Alston-Bannarn Harlem Art Workshop in Harlem/NYC, NY. He was intimately associated with the "Harlem Renaissance" of the 1930s, being considered as one of the movement's preeminent contributors. [1] Although he is primarily known for his work in sculpture, he was equally skilled as a figurist and character artist in the various paint mediums, Conté crayon, pastel, free-form sketch, etc.

In 1941, he returned to Minnesota and entered a piece of sculpture in the Minnesota State Fair sculpture competition, where he was awarded the first prize. The much-honored artist had won a painting prize at the fair a decade earlier as well, representing one of the earliest achievements by an African-American artist in that state's history.

His works are represented in some of the most important collections in the US, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institution, Dartmouth College's Hood Museum of Art, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Minnesota Historical Society, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Howard University Gallery of Art, and Clark Atlanta University Art Galleries. Very few Bannarn works exist in private hands.

At the April 26, 2007 sale conducted by Shannon's Fine Art Auctioneers, Milford, Connecticut, a Bannarn original oil titled "Modernist Exhibition" sold for $24,000 USD, achieving a price nearly ten times its pre-auction estimate of $2500–$3500.[1]At a May 18, 2008, auction conducted by the Rose Hill Auction Gallery, Englewood, New Jersey, an oil on board painting by Bannarn entitled "Seagulls" sold for $5,750, almost twenty times its pre-auction estimate of $200–$300.[2]

He died on September 20, 1965, in Brooklyn, New York.

Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Bannarn

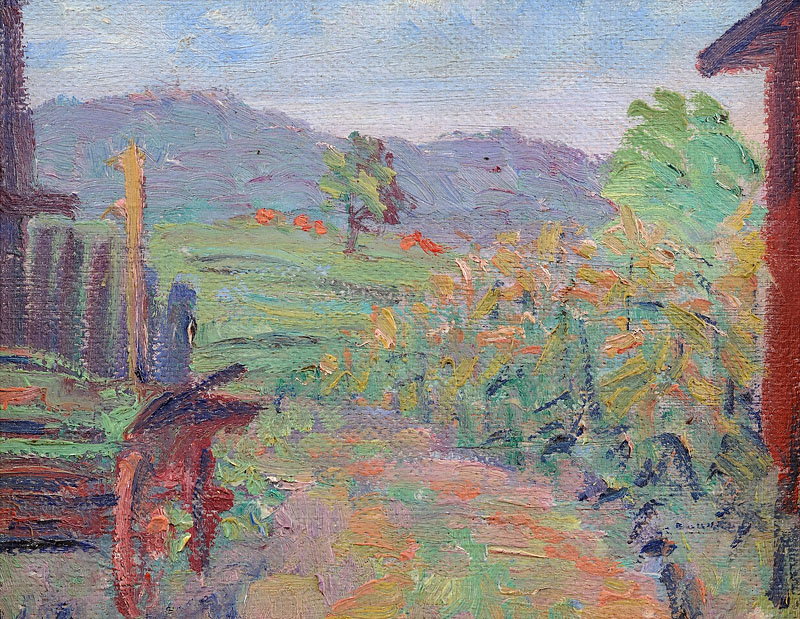

Country Road Missouri

Watercolor

9x12 inches

1941

Signed

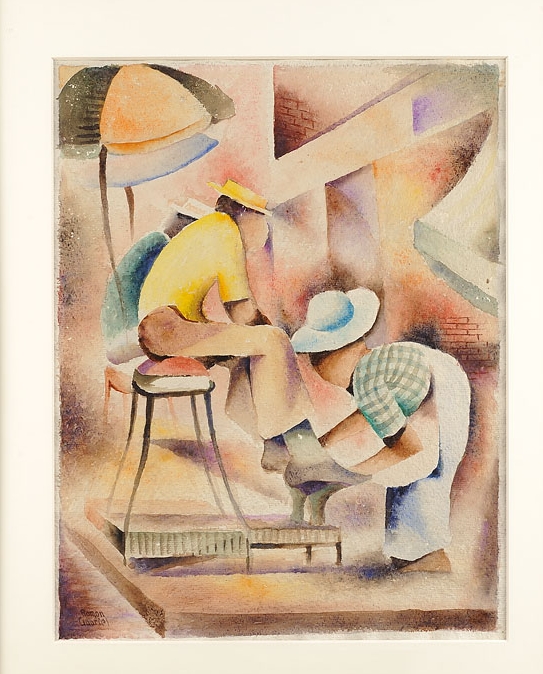

Tourist Car Passenger

Mixed media on paper

9 1/4x7 1/2 inches

1940

Not signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Ernie Barnes (1938-2009)

Ernest Eugene Barnes, Jr. (July 15, 1938 – April 27, 2009) was an African-American painter, well known for his unique style of elongation and movement. He was also a professional football player, actor and author.

Ernest Barnes, Jr. was born during Jim Crow in "the bottom" community of Durham, North Carolina, near the Hayti District of the city. His father, Ernest E. Barnes, Sr. (1899–1966) worked as a shipping clerk for Liggett Myers Tobacco Company in Durham. His mother, Fannie Mae Geer (1905–2004) oversaw the household staff for prominent Durham attorney and local Board of Education member Frank L. Fuller, Jr.

On days when Fannie allowed "June" (Barnes' nickname to family and childhood friends) to accompany her to the Fuller home, Barnes had the opportunity to peruse the art books and listen to classical music. The young Ernest was intrigued and captivated by the works of master artists. By the time Barnes entered the first grade, he was familiar with the works of such masters as Toulouse-Lautrec, Delacroix, Velasquez, Rubens, and Michelangelo. When he entered junior high, he could appreciate, as well as decode, many of the cherished masterpieces within the walls of mainstream museums – although it would be a half dozen more years before he was allowed entrance because of his race.[1]

A self-described chubby and unathletic child, Barnes was taunted and bullied by classmates. He continually sought refuge in his sketchbooks, hiding in the less-traveled parts of campus away from other students. One day in a quiet area, Ernest was found drawing in a notebook by the masonry teacher, Tommy Tucker, who was also the weightlifting coach and a former athlete. Tucker was intrigued with Barnes' drawings so he asked the aspiring artist about his grades and goals. Tucker shared his own experience of how bodybuilding improved his strength and outlook on life. That one encounter would begin Barnes' discipline and dedication that would permeate his life. In his senior year at Hillside High School, Barnes became the captain of the football team and state champion in the shot put.[2]

In 1956 Barnes graduated from Hillside High School with 26 athletic scholarship offers. Segregation prevented him from attending nearby Duke or the University of North Carolina. His mother promised him a car if he lived at home, so he chose North Carolina College at Durham (formerly North Carolina College for Negroes, now North Carolina Central University). He majored in art on a full athletic scholarship. His college track coach was the famed Dr. Leroy T. Walker.[1] Barnes played the football positions of tackle and center at NCC at Durham.

At age 18, on a college art class field trip to the newly desegregated North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, Barnes inquired where he could find "paintings by Negro artists." The docent responded, "Your people don't express themselves that way."[3] Poetic justice prevailed 23 years later in 1979 when Barnes returned to the museum for a solo exhibition, hosted by North Carolina Governor James Hunt.

In 1990 Barnes was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts by North Carolina Central University.

In 1993 Barnes was selected to the "Black College Football 100th Year All-Time Team" by the Sheridan Broadcasting Network.[4]

In 1999 Barnes was bestowed "The University Award", the highest honor by The University of North Carolina Board of Governors.[5]

In December 1959 Barnes was drafted in the 10th round by the then-World Champion Baltimore Colts. He was originally selected in the 8th-round by the Washington Redskins,[6] who renounced the pick minutes after discovering he was a Negro.

Shortly after his 22nd birthday, while at the Colts training camp, Barnes was interviewed by N.P. Clark, sportswriter for the Baltimore News-Post newspaper. Until then Barnes was always known by his birth name, Ernest Barnes. But when Clark's article appeared on July 20, 1960, it referred to him as "Ernie Barnes," which changed his name and life forever.[7]

Barnes credits his college art instructor Ed Wilson for laying the foundation for his development as an artist. Wilson was a sculptor who instructed Barnes to paint from his own life experiences. "He made me conscious of the fact that the artist who is useful to America is one who studies his own life and records it through the medium of art, manners and customs of his own experiences."[18]

All his life, Barnes was ambivalent about his football experience. In interviews and in personal appearances, Barnes said he hated the violence and the physical torment of the sport. However, his years as an athlete gave him unique, in-depth observations. "(Wilson) told me to pay attention to what my body felt like in movement. Within that elongation, there's a feeling. And attitude and expression. I hate to think had I not played sports what my work would look like."[19]

Barnes' first painting sale was in 1959 for $90 to Boston Celtic Sam Jones for a painting called Slow Dance.[1] It was subsequently lost in a fire at Jones' home.

Critics have defined Barnes' work as neo-mannerist.[20] Based on his signature use of serpentine lines, elongation of the human figure, clarity of line, unusual spatial relationships, painted frames, and distinctive color palettes, art critic Frank Getlein credited Barnes as the founder of the neo-Mannerism movement - because of the similarity of technique and composition prevalent during the 16th century, as practiced by such masters as Michelangelo and Raphael.[21]

Numerous artists have been influenced by Barnes' art and unique style. Accordingly, several copyright infringement lawsuits have been settled and are currently pending.

Ernie Barnes framed his paintings with distressed wood in homage to his father. In his 1995 autobiography, artist Ernie Barnes wrote of his father: “... with so little education, he had worked so hard for us. His legacy to me was his effort, and that was plenty. He knew absolutely nothing about art.”[1]

Weeks before Ernie Barnes’ first solo art exhibition in 1966, he was at the family home in Durham, North Carolina as his father lay in the hospital after suffering a stroke. He noticed the usually well-maintained white picketed fence had gone untended since his father’s illness. Days later, Ernest E. Barnes, Sr. died. “I placed a painting against the fence and stood away and had a look. I was startled at the marriage between the old wood fence and the painting. It was perfect. In tribute, Daddy’s fence would hug all my paintings in a prestigious New York gallery. That would have made him smile.”[1]

A consistent and distinct feature in Barnes' work is the closed eyes of his subjects. "It was in 1971 when I conceived the idea of The Beauty of the Ghetto as an exhibition. And I exposed it to some people who were black to get a reaction. And from one (person) it was very negative. And when I began to express my points of view (to this) professional man, he resisted the notion. And as a result of his comments and his attitude I began to see, observe, how blind we are to one another's humanity. Blinded by a lot of things that have, perhaps, initiated feelings in that light. We don't see into the depths of our interconnection. The gifts, the strength and potential within other human beings. We stop at color quite often. So one of the things we have to be aware of is who we are in order to have the capacity to like others. But when you cannot visualize the offerings of another human being you're obviously not looking at the human being with open eyes."[22] "We look upon each other and decide immediately: This person is black, so he must be... This person lives in poverty, so he must be..."[13]

Barnes died on April 27, 2009 at Cedars Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, California from blood cancer.[46] He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in Durham, North Carolina near the site of where his family home once stood, and at the beach in Carmel, California, one of his favorite cities.

Link to the full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernie_Barnes

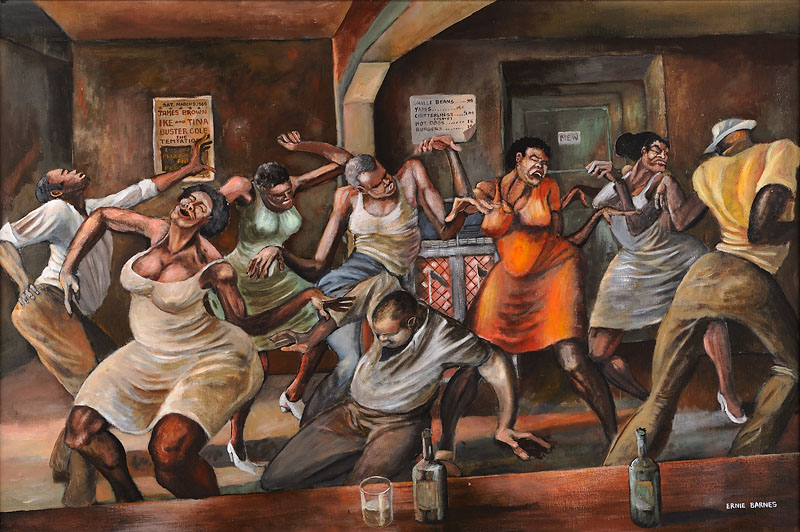

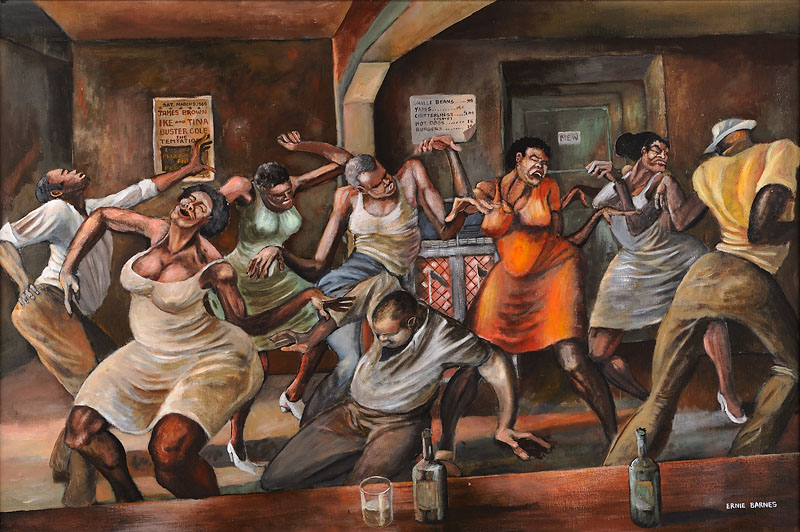

Dance Hall

Oil on board

24x36 inches

1969

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Slam Dunk

Acrylic on canvas

60x27 inches

c.1970

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

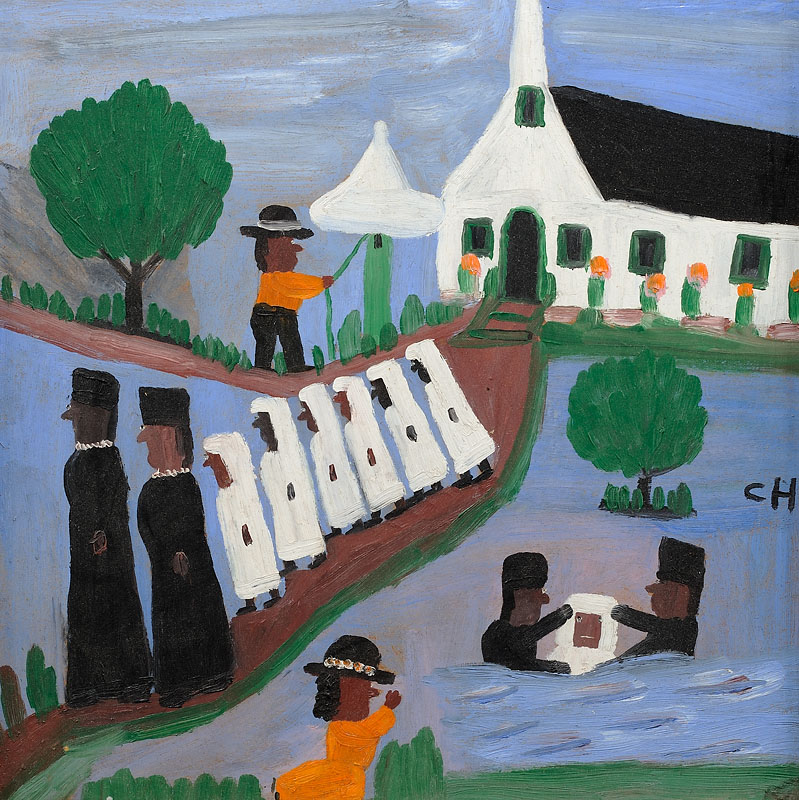

Romare Bearden (1911-1988)

Romare Bearden (September 2, 1911 – March 12, 1988) was an Afro-American artist. He worked with many types of media including cartoons, oils and collages. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, educated in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Bearden moved to New York City after high school and went on to graduate from NYU in 1935. He began his artistic career creating scenes of the American South. Later, he endeavored to express the humanity he felt was lacking in the world after his experience in the US Army during World War II on the European front. He later returned to Paris in 1950 and studied Art History and Philosophy at the Sorbonne in 1950.

Bearden's early work focused on unity and cooperation within the African-American community. After a period during the 1950s when he painted more abstractly, this theme reemerged in his collage works of the 1960s, when Bearden became a founding member of the Harlem-based art group known as The Spiral, formed to discuss the responsibility of the African-American artist in the struggle for civil rights.

Bearden was the author or coauthor of several books, and was a songwriter who co-wrote the jazz classic "Sea Breeze", which was recorded by Billy Eckstine, a former high school classmate at Peabody High School, and Dizzy Gillespie. His lifelong support of young, emerging artists led him and his wife to create the Bearden Foundation to support young or emerging artists and scholars. In 1987, Bearden was awarded the National Medal of Arts. His work in collage led the New York Times to describe Bearden as “the nation's foremost collagist”[1] in his 1988 obituary.

Bearden was born in Charlotte, North Carolina. Bearden's family moved him to New York City as a toddler, and their household soon became a meeting place for major figures of the Harlem Renaissance.[2] His mother, Bessye Bearden, played an active role with New York City's Board of Education, and also served as founder and president of the Colored Women's Democratic League. Bessye Bearden was also a New York correspondent for The Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper.[3] Young Romare Bearden traveled frequently, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and to visit family members in Charlotte, North Carolina.

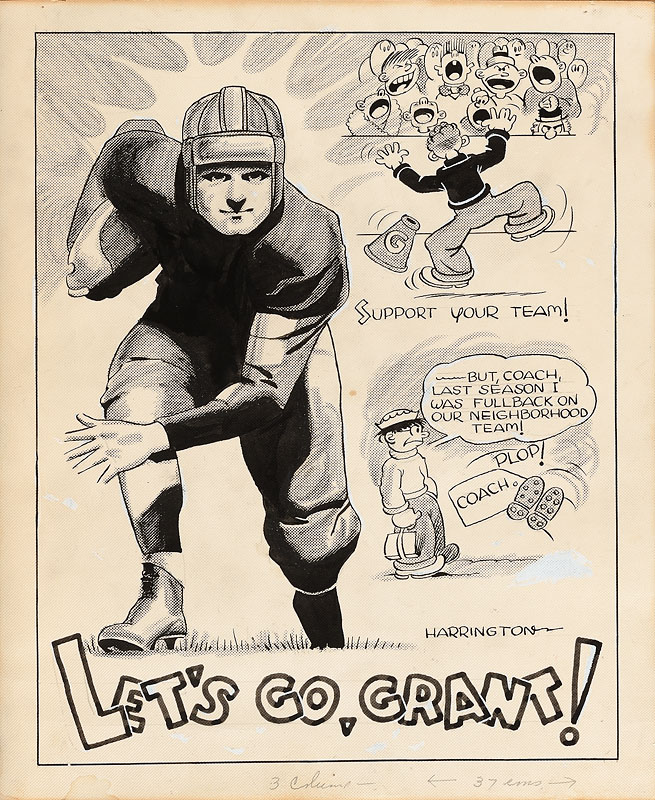

In 1929 he graduated from Peabody High School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He then enrolled in Lincoln University, the nation's first Historically Black College and University founded in 1854. He later transferred to Boston University where he served as art director for Beanpot, Boston University's student humor magazine.[4]Bearden continued his studies at New York University (NYU), where he started to focus more on his art and less on athletics, and became a lead cartoonist and art editor for the Eucleian Society's (a secretive student society at NYU) monthly journal, The Medley.[5] Bearden studied art, education, science and mathematics, graduating with a degree in science and education in 1935. He continued his artistic study under German artist George Grosz at the Art Students League in 1936 and 1937. During this period he supported himself as a political cartoonist for African-American newspapers, including the Baltimore Afro-American, where he did a weekly cartoon from 1935 until 1937.[6]

During his career, Bearden received the following honorary doctorates: Pratt Institute, New York, 1973; Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, 1975; Maryland Institute of Art, Baltimore, 1976; North Carolina Central College University, Durham, 1977; and Davidson College, North Carolina, 1978.[7]

Bearden grew as an artist not by learning how to create new techniques and mediums, but by his life experiences. His early paintings were often of scenes in the American South, and his style was strongly influenced by the Mexican muralists, especially Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. In 1935, Bearden became a case worker for the Harlem office of the New York City Department of Social Services.[3] Throughout his career as an artist, Bearden worked as a case worker off and on to supplement his income.[3] During World War II, Bearden joined the United States Army, serving from 1942 until 1945.[7] After serving in the army, Bearden joined the Samuel Kootz Gallery, an avant-garde commercial gallery in New York, where he produced paintings in "an expressionistic, linear, semi-abstract style."[3] He would return to Europe in 1950 to study philosophy with Gaston Bachelard and art history at the Sorbonne under the auspices of the GI Bill.[3][7] Bearden then traveled throughout Europe visiting Picasso and other artists.[3]

This completely changed his style of art as he started producing abstract representations of what he deemed as human; specifically scenes from the Passion of the Christ. He had evolved from what Edward Alden Jewell, a reviewer for the New York Times, called a "debilitating focus on Regionalist and ethnic concerns" to what became known as his stylistic approach which participated in the post-war aims of avant-garde American art.[8] His works were exhibited at the Samuel M. Kootz gallery until his work was deemed not abstract enough.

During his success in the gallery, however, he produced Golgotha, a painting from his series of the Passion of the Christ (see Figure 1). Golgotha is an abstract representation of the Crucifixion. The eye of the viewer is drawn to the middle of the image first, where Bearden has rendered Christ's body. The body parts are stylized into abstract geometric shapes, yet still too realistic to be concretely abstract; this work has a feel of early Cubism. The body is in a central position and yet darkly contrasting with the highlighted crowds. The crowds of people are on the left and right, and are encapsulated within large spheres of bright colors of purple and indigo. The background of the painting is depicted in lighter jewel tones dissected with linear black ink. Bearden used these colors and contrasts because of the abstract influence of the time, but also for their meanings.

Bearden intended to not focus on Christ but he wanted to emulate rather the emotions and actions of the crowds gathered around the Crucifixion. He worked hard to "depict myths in an attempt to convey universal human values and reactions".[9]According to Bearden himself, Christ's life, death, and resurrection are the greatest expressions of man's humanism, not because of Christ's actual existence but the idea of him that lived on through other men. This is why Bearden focuses on Christ's body first, to portray the idea of the myth, and then highlights the crowd, to show how the idea is passed on to men.

While it may seem as if Bearden was emphasizing the Biblical interpretations of Christ and the Crucifixion, he was actually focusing on the spiritual intent. He wanted to show ideas of humanism and thought that cannot be seen by the eye, but "must be digested by the mind".[10] This is in accordance with the time he produced this image, as other famous artists creating avant-garde abstract representations of historically significant events, such as Robert Motherwell’s commemoration of the Spanish Civil War, Jackson Pollock’s investigation of the Northwest Coast Indian art, Mark Rothko’s and Barnett Newman’s interpretations of Biblical stories, etc. Bearden used this form of art to depict humanity during a period of time when he didn’t see humanity in existence through the war.[5] However, Bearden stands out from these other artists as his works, including Golgotha, are a little too realistic for this time, and he was kicked out of Sam Kootz's gallery.

Bearden turned to music, co-writing the hit song Sea Breeze, which was recorded by Billy Eckstine and Dizzy Gillespie; it is still considered a jazz classic.[11] In 1954, at age 42, he married Nanette Bearden, a 27-year-old dancer who herself became an artist and critic. The couple eventually created the Bearden Foundation to assist young artists.

In the late 1950s, Bearden's work became more abstract, using layers of oil paint to produce muted, hidden effects. In 1956, Bearden began studying with a Chinese calligrapher, whom he credits with introducing him to new ideas about space and composition in painting. He also spent a lot of time studying famous European paintings he admired, particularly the work of the Dutch artists Johannes Vermeer, Pieter de Hooch, and Rembrandt. He began exhibiting again in 1960. About this time the couple established a second home in the Caribbean island of St. Maarten. In 1961, Bearden joined the Cordier and Ekstrom Gallery in New York City, which would represent him for the rest of his career.[3]

In the early 1960s in Harlem, Bearden was a founding member of the art group known as The Spiral formed "for the purpose of discussing the commitment of the Negro artist in the present struggle for civil liberties, and as a discussion group to consider common aesthetic problems."[12] The first meeting was held in Bearden's studio on July 5, 1963 and was attended by Bearden, Hale Woodruff, Charles Alston, Norman Lewis, and James Yeargans, Felrath Hines, Richard Mayhew, and William Pritchard. Woodruff was responsible for naming the group The Spiral suggesting the way in which the Archimedes spiral ascends upward as a symbol of progress. Over time the group expanded to include Merton Simpson, Emma Amos, Reginald Gammon Alvin Hollingsworth, Calvin Douglas, Perry Ferguson, William Majors and Earle Miller. Stylistically the group ranged from Abstract Expressionists to social protest painters.[12]

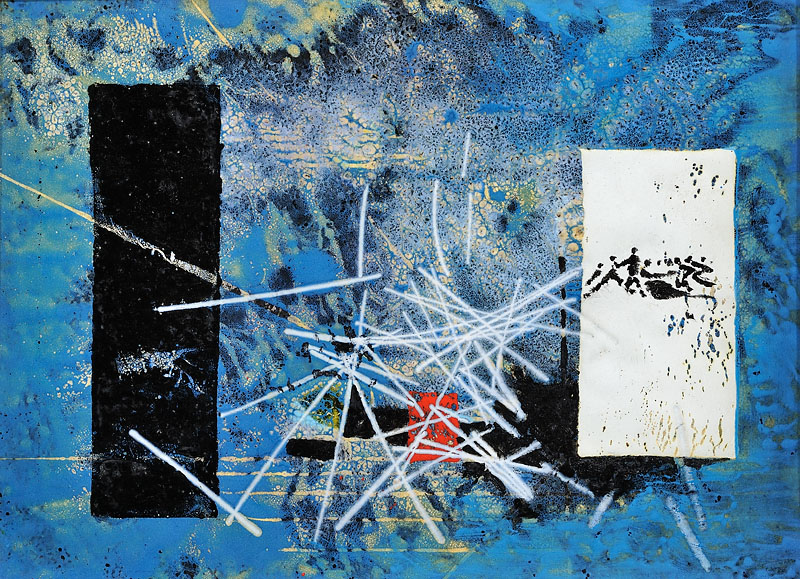

Bearden's collage work began in 1963 or 1964.[3] Bearden created his collages by first combining images cut from magazines and colored paper, which he would often with further alter with the use of sandpaper, bleach, graphite or paint.[3] Bearden would then enlarge these collages through the photostat process.[3] Building on the momentum from a successful exhibition of his photostat pieces at the Cordier and Ekstrom Gallery in 1964, Bearden was invited to do a solo exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which increased his public profile.[3] Bearden's collage techniques changed over the years and in later pieces, he would use blown-up photostat photographic images, silk-screened, colored paper, and billboard pieces to create large collages on canvas and fiberboard.[3]

In 1971, the Museum of Modern Art held a retrospective exhibition of Bearden's work.[3]

His early works suggest the importance of African Americans' unity and cooperation. For instance, The Visitation implies the importance of collaboration of black communities by depicting intimacy between two black women who are holding hands together. However, not only because of the message conveyed, but also Bearden's vernacular realism represented in the work makes The Visitation noteworthy; Bearden describes two figures in The Visitation somewhat realistically but does not fully follow the pure realism by distorting and exaggerating some parts of their body, to “convey an experiential feeling or subjective disposition.”[13] Bearden’s quotation also demonstrates his supportive view to vernacular realism: “the Negro artists [...] must not be content with merely recording a scene as a machine. He must enter wholeheartedly into the situation he wishes to convey.”[13]

In 1942, Bearden produced Factory Workers (gouache on casein on brown kraft paper mounted on board), which was commissioned by Forbes magazine to accompany an article titled The Negro's War.[14] The article "examined the social and financial costs of racial discrimination during wartime and advocated for full integration of the American workplace."[15] Factory Workers and its companion piece Folk Musicians serve as prime examples of the influence that Mexican muralists played in Bearden's early work.[14][15]

Bearden had struggled with two artistic sides of himself: his background as “a student of literature and of artistic traditions, and being a black human being involves very real experiences, figurative and concrete”,[16] which was at combat with the mid-twentieth century “exploration of abstraction”.[17] His frustration with abstraction won over, as he himself described his paintings’ focus as coming to a plateau. Bearden then turned to a completely different medium at a very important time for the country.

During the 1960s civil rights movement, Bearden started to experiment again, this time with forms of collage.[18] After helping to found an artists group in support of civil rights, Bearden's work became more representational and more overtly socially conscious. He used clippings from magazines, which in and of itself was a new medium as glossy magazines were fairly new. He used these glossy scraps to incorporate modernity in his works, trying to show how not only were African-American rights moving forward, but so was his socially conscious art. In 1964, he held an exhibition he called Projections, where he introduced his new collage style. These works were very well received, and these are generally considered to be his best work.[19]

There have been numerous museum shows of Bearden's work since then, including a 1971 show at the Museum of Modern Artentitled Prevalence of Ritual, an exhibition of his highly prized prints entitled A Graphic Odyssey showing the work of the last fifteen years of his life,[20] and the 2005 National Gallery of Art retrospective entitled The Art of Romare Bearden. In 2011, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery exhibited its second show of the artist's work, Romare Bearden (1911–1988): Collage, A Centennial Celebration, an intimate grouping of 21 collages produced between 1964 and 1983.[21]

One of his most famous series, Prevalence of Ritual, concentrated mostly on southern African-American life. He used these collages to show his rejection of the Harmon Foundation’s (a New York City arts organization) emphasis on the idea that African Americans must reproduce their culture in their art.[22] Bearden found this to be a burden on African artists, because he saw this idea creating an emphasis on reproducing something that already exists in the world. He used this new series to speak out against this limitation on Black artists, and to emphasize modern art.

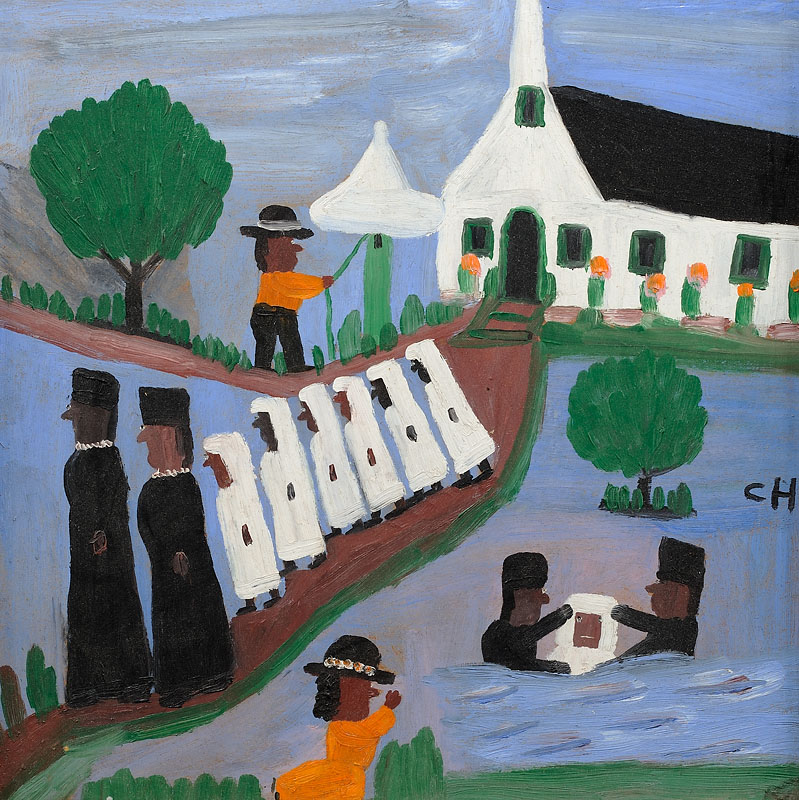

In this series, one of the pieces is entitled Baptism. Bearden was influenced by Francisco de Zurbarán, and based Baptism on Zurbarán’s painting The Virgin Protectress of the Carthusians. Bearden wanted to show how the water that is about to be poured on the subject being baptized is always moving, giving the whole collage a feel and sense of temporal flux. This is a direct connection with the fact that African Americans’ rights were always changing, and society itself was in a temporal flux at the time he created this image. Bearden wanted to show how nothing is fixed, and represented this idea throughout the image: not only is the subject being baptized about to have water poured from the top, but the subject is also about to be submerged in water. Every aspect of the collage is moving and will never be the same more than once, which was congruent with society at the time.

In "The Art of Romare Bearden", Ruth Fine describes his themes as "universal". "A well-read man whose friends were other artists, writers, poets and jazz musicians, Bearden mined their worlds as well as his own for topics to explore. He took his imagery from both the everyday rituals of African American rural life in the south and urban life in the north, melding those American experiences with his personal experiences and with the themes of classical literature, religion, myth, music and daily human ritual."

A mural by Romare Bearden in the Gateway Center subway station in Pittsburgh is worth $15 million, more than the cash-strapped transit agency expected, raising questions about how it should be cared for once it is removed before the station is demolished. "We did not expect it to be that much," Port Authority of Allegheny County spokeswoman Judi McNeil said. "We don't have the wherewithal to be a caretaker of such a valuable piece." It would cost the agency more than $100,000 a year to insure the 60-foot-by-13-foot tile mural, McNeil said. Bearden was paid $90,000 for the project, titled "Pittsburgh Recollections." It was installed in 1984.[23]

Before his death, Bearden claimed the collage fragments aided him in ushering the past into the present: "When I conjure these memories, they are of the present to me, because after all, the artist is a kind of enchanter in time."[24]

The Return of Odysseus, one of his collage works in the Art Institute of Chicago, exemplifies Bearden's effort to actively represent African-American rights in a form of collage. This collage describes one of the scenes in Homer's epic Odyssey, in which the hero Odysseus is returning home from his long journey. When one first sees the collage, the focal point that first captures one's eyes is the main figure, Odysseus, situated at the center of the work reaching his hand to his wife. However, if one takes a closer look at Odysseus, he or she would wonder why Odysseus and his wife, as well as all the other figures in the collage, are depicted as blacks, since according to the original story, Odysseus is a Greek king. This is one of the ways in which Bearden actively endeavours in his collage works to represent African-American rights; by replacing white characters with blacks, he attempts to defeat the rigidness of racial roles and stereotypes and open up the possibilities and potentials of blacks. In addition, the original epic depicts Odysseus as a strong character who has overcome numerous difficulties, and thus “Bearden may have seen Odysseus as a strong mental model for the African-American community, which had endured its own adversities and setbacks.”[25] Therefore, by describing Odysseus as black, Bearden maximizes the effect of potential black audiences empathizing to Odysseus.

One may wonder why Bearden chose the technique of collage to support the Civil Rights Movement and assert African-American rights. The reason he used this technique was because “he felt that art portraying the lives of African Americans did not give full value to the individual. [...] In doing so he was able to combine abstract art with real images so that people of different cultures could grasp the subject matter of the African American culture: The people. This is why his theme always exemplified people of color.”[26] In addition, collage’s technique of gathering several pieces together to create one assembled work “symbolizes the coming together of tradition and communities.”[25]

Romare Bearden died in New York City on March 12, 1988 due to complications from bone cancer. In their obituary for him, the New York Times called Bearden "one of America's pre-eminent artists" and "the nation's foremost collagist."[1]

Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romare_Bearden

Mecklenburg Morning

Mixed media collage on board

14x18 inches

1978

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Old Couple

Mixed media collage on board

6x9 inches

1978

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

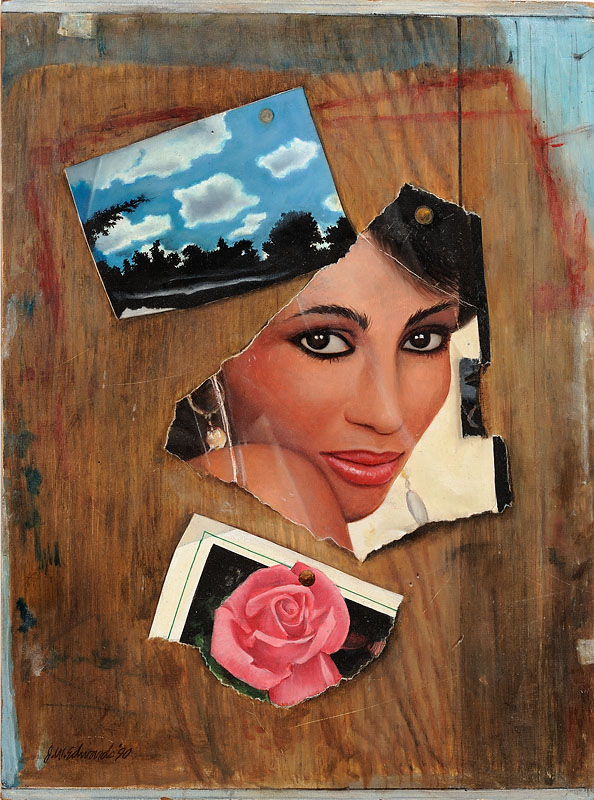

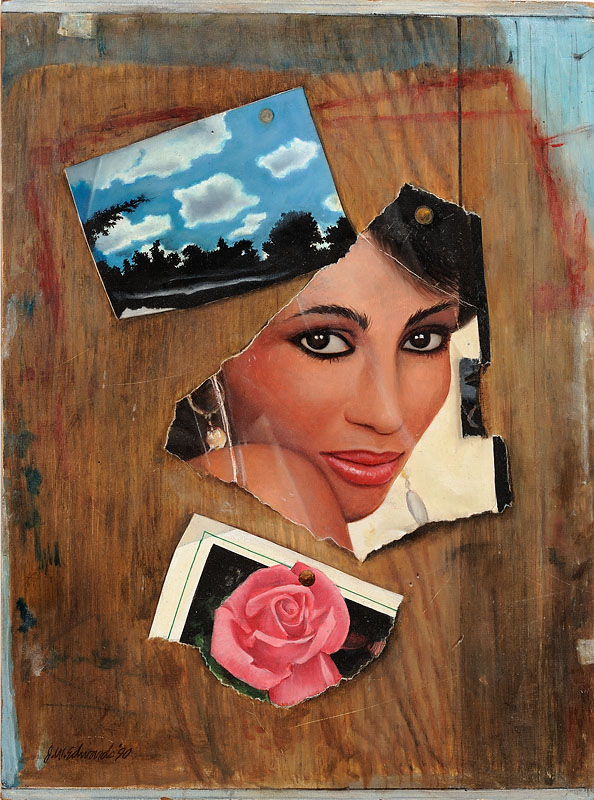

Cleveland Bellow (1951-2009)

Catch a Southern Beauty

Photo Transfer Collage

23 1/4x19 1/2 inches

Year unknown

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Robert Blackburn (1920-2003)

Robert Hamilton Blackburn (December 10, 1920 – April 21, 2003) was an African-American artist, teacher and printmaker. Blackburn was born in Summit, New Jersey, to parents who were from Jamaica, and he grew up in Harlem, where his family moved when he was seven years old.[1] He attended P.S. 139 and then Frederick Douglass Junior High School (1932–36), where his English teacher was Countee Cullen. Starting in 1936, he went to DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, where he worked on the literary magazine The Magpie as a writer and artist.[2] He graduated in 1940.

And at the age of 13, he began attending classes at the Harlem Arts Community Center operated by the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project, studying with Charles Alston and Augusta Savage, among others. He studied lithographyand other print-making techniques with Riva Helfond, and he frequented the Uptown Community Workshop, a gathering place for black artists and writers such as Langston Hughes, Richard Wright and Jacob Lawrence.

From early prints that portrayed cityscapes and figures on abstract backgrounds, he moved into more abstract work. From 1940 to 1943, a work scholarship to the Art Students League made it possible for him to study painting with Vaclav Vytlacil and lithography with Will Barnet, who became his friend. Between 1943 and 1948 he supported himself with difficulty with arts-related freelance work, producing maps, charts and other graphics.

In 1948, Barnet helped Blackburn establish the Printmaking Workshop, an 8,000-square-foot (740 m2) loft at 55 West 17th Street in New York City.[3] In the early 1950s, Blackburn and Barnet produced a suite of Barnet's lithographs that were a technical tour de force, requiring up to seventeen colors and multiple stones in the printing process.[4]

Blackburn was famously generous to other artists who came through the Workshop and fostered an atmosphere of openness to diversity. Among the many artists who have worked with Blackburn at the Printmaking Workshop are Leonora Carrington, Roy DeCarava, Faith Ringgold, Betye Saar, and Faith Wilding. His commitment to sponsoring minority and third-world students and developing community programs profoundly influenced younger printmakers, who seeded similar workshops around the United States and internationally.[5]

In 1956, when the Printmaking Workshop struggled financially and faced the threat of closing, fellow artist and printmaker Chaim Koppelman devised a means to save the studio by transforming it into a cooperative with annual dues. Blackburn credited Koppelman with saving the Workshop, and in 1992, Blackburn, Barnet, and Koppelman received a New York Artists Equity Award for their "dedicated service to the printmaking community."[6]

Blackburn's most productive period as an artist and printmaker was between the late 1950s and the early 1970s.[4] During this period he produced a large body of abstract still lifes and color compositions, mostly in lithography. In the 1970s, Blackburn turned away from lithography and began producing woodcuts, as well as some monotypes and intaglios.

Blackburn also served between 1957 and 1963 as the first master printer at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), where he produced editions for such artists as Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Larry Rivers.[4]

In 1971, Blackburn put in place a board of trustees to help run the Printmaking Workshop and incorporated it as a nonprofit. Over the years the Workshop had accumulated a large collection of artists' prints, and efforts to find a permanent home for them were led by Deborah Cullen, who was the collection's curator between 1993 and 1996. By 1997, over 2,500 of these works had been deposited with the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. Smaller selections of the Workshop's prints have been placed with the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and El Museo Del Barrio, New York.

Over the years, Blackburn taught at the New School for Social Research, Cooper Union, Pratt Institute, and Columbia University. In 1981, Blackburn was elected to the National Academy of Design as an Associate member, and he became a full member in 1994. In 1988, Blackburn and the nonprofit Printmaking Workshop received a Governor's Art Award from the New York State Council on the Arts. He also received a MacArthur fellowship in 1992. He died in New York City.[7]

On September 18, 2003, the Great Hall of Cooper Union in New York City held an exhibition and memorial to honor the work of this master printer, artist, and teacher. Blackburn's early work at DeWitt Clinton High School, where classmates included artists Burton Hasen, David Finn and Harold Altman, was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum in 2009.

Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Blackburn_(artist)

Yellow on Red

Serigraph

19x24 inches

1962

Signed and dated

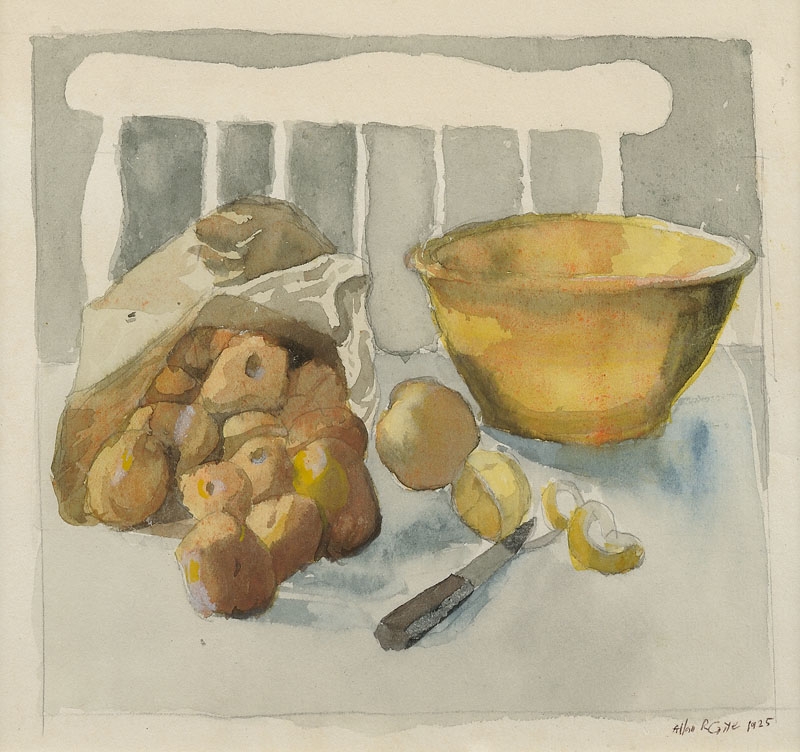

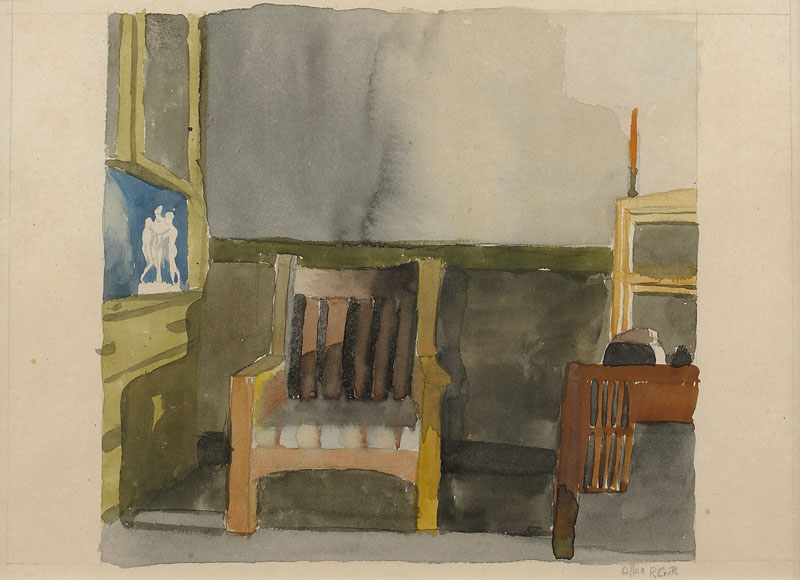

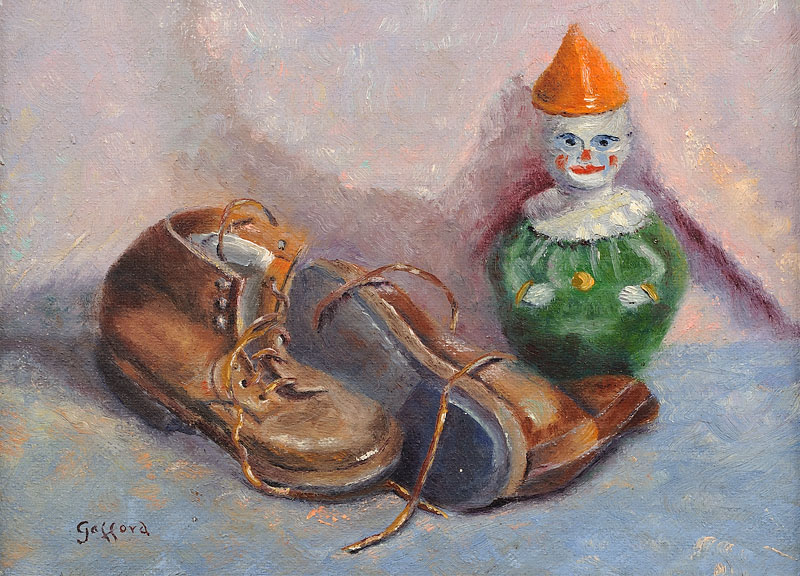

Charles Bohannah (1910-1985)

Charles Bohannah, a native New Yorker, was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1910. Bohannah began his career as an artist in high school, later enrolling in the Cooper Union School of Art. Around this time Bohannah also joined the prestigious Art Students League. While studying drawing and painting, he began doing "wash drawings" for use in magazines. Bohannah's first critical success was winning a scholarship, as a result of an exhibition at the Roak Art Museum in New York. This occurred around the beginning of World War II, when Charles chose to attend the Bell Signal Corp. School of radio to help the war effort.

During the war, Bohannah began to use photography as a means of self expression, working in both color and black and white. After the war, Bohannah resumed his artistic career working in oils, producing figurative, landscape as well as still life compositions. In 1976, Bohannah enjoyed success again with a solo exhibition at the Humanities Gallery of Long Island University as well as at the Community Gallery at the Brooklyn Museum. It was reported that in 1977, Nelson A. Rockefeller then Governor of New York State, began collecting Bohannahs work. For eleven years, Bohannah showed work at the Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibition, winning several awards.

Charles Bohannah died in New York , 1985.

Link to full bio: http://www.askart.com/artist_bio/Charles_F_Bohannah/10005355/Charles_F_Bohannah.aspx

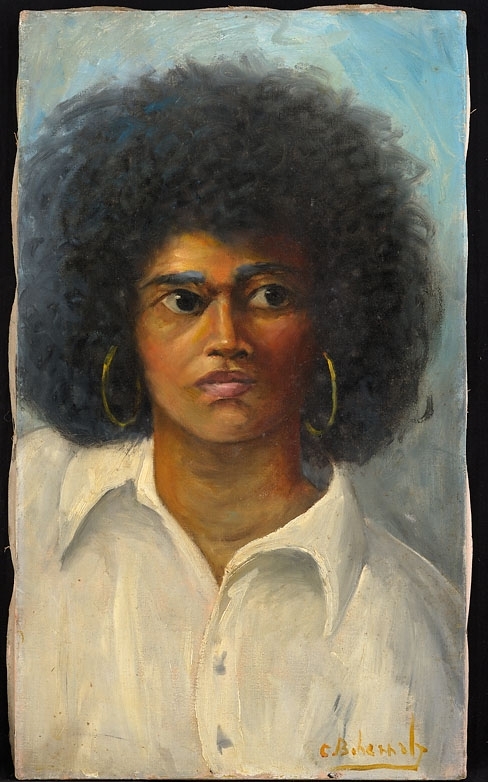

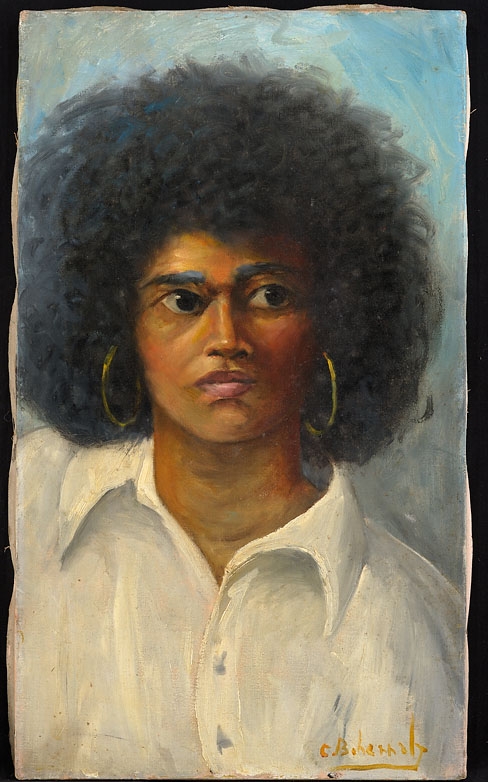

Portrait of a Woman

Oil on canvas

24x14 inches

c. 1950

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

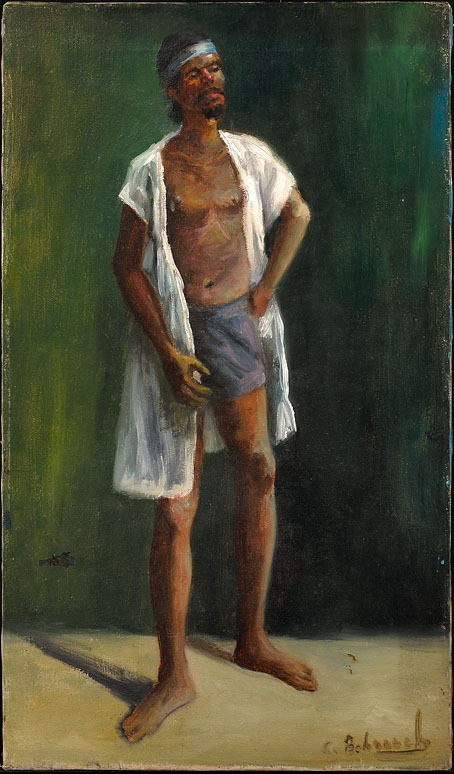

Standing Man

Oil on canvas

24x30 inches

c. 1950

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Seated Woman

Oil on canvas

24x14 inches

c. 1940

Signed and includes artist's business card on verso with Brooklyn, NY address

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

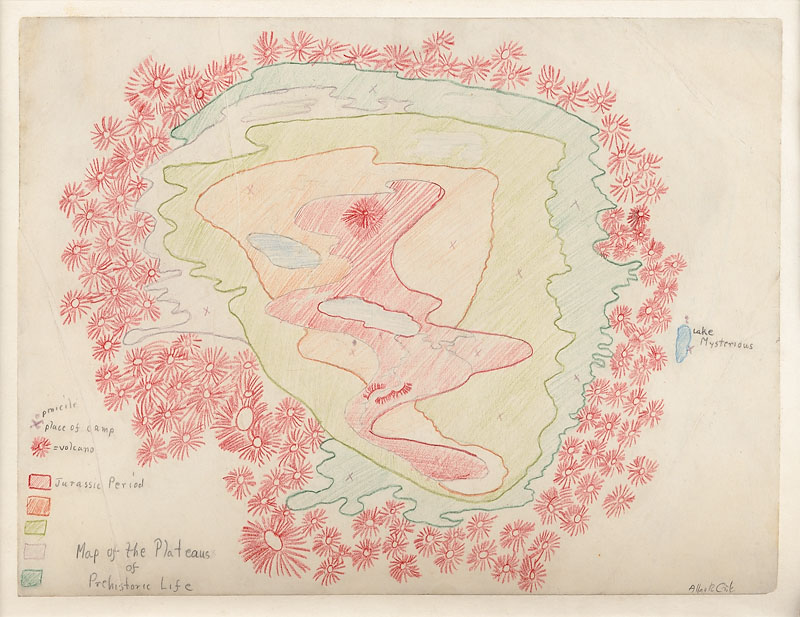

Benjamin Britt (b.1923)

Seven African Men Dancing

Oil on canvas

24x48

c. 1970

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Benjamin Britt, born in Windfall, North Carolina, attended Philadelphia's Museum College of Art, Hussian School of Art, and the Arts Student League in New York City. Britt's oil paintings and charcoal drawings, seen in some of the finest private collections in the country, range from strong symbolic African themes, charcoal drawings depicting neighborhood children, beautifully rendered portraits, to his widely acclaimed surrealist works. These works form a sense of balance, and space and present strong symbolic messages that cannot be ignored.

Bio found on: http://www.askart.com/artist/Benjamin_Britt/10006654/Benjamin_Britt.aspx

Grafton Tyler Brown (1841-1918)

Cascade Cliffs, Columbia River

Oil on canvas

17x32 inches

1885

The Golden Gate

Oil on canvas

30x20 inches

1887

Gold Stream Falls

Oil on canvas

21x12 1/2 inches

1883

Grand Canyon and Falls

Oil on canvas

30x20 inches

1887

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Grafton Tyler Brown was a cartographer, lithographer, and painter, widely considered the first professional African American artist in California. Born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1841, Brown learned lithography in Philadelphia and then became part of a cohort of African Americans who sought better economic and social opportunities in the West during the 1850s.

Brown migrated to San Francisco in the mid-1850s, where he found work as a lithographer at Kuchel and Dresel. He bought the business in 1867 and renamed it G.T. Brown & Co., continuing his efforts to document the gold rush towns and other Bay Area settlements. Brown sold his business in 1872 in order to devote his time to traveling and painting. In 1882, Brown settled in Victoria, British Columbia, where he opened a studio. During Brown’s travels throughout the Pacific Northwest, his work transformed from concentrating on commercial and expansionist aims, to focusing on the loss of open lands and the need to preserve them. In 1886 Brown moved to Portland, Oregon where he belonged to the Portland Art Society and opened up his own studio. He left Portland for Helena, Montana in 1890. While in Helena Brown continued his work and produced a map of Yellowstone Park which was published in 1894. By that point, however, Brown had moved on. He arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1892 to begin work as a draughtsman for the U.S. Army Engineer's Office. Brown spent the rest of his life in the Minnesota city and died there in 1918.

Brown's maps, prints, and paintings are housed in archives in Victoria, British Columbia, San Francisco, California, and Tacoma, Washington. Major exhibitions of his work in Los Angeles, Oakland, and Tacoma demonstrate Brown's significant contribution to the settlement of the West as well as reflecting the beauty and diversity of the Pacific Northwest.

Bio found on: http://www.blackpast.org/aaw/brown-grafton-tyler-1841-1918

Selma Burke (1900-1995)

Female Torso

Bronze

6 1/4x3x2 inches

1995

Untitled (Facial Sculpture)

Bronze

12x 1/4x7x4 inches

unknown

Monument to the Tuskegee Airmen

Bronze

9 1/4x6x6 inches

1942

Female Bust

Plaster

17x10x10 inches

1973

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Selma Hortense Burke (December 31, 1900 – August 29, 1995) was an American sculptor and a member of the Harlem Renaissance movement.[1] Burke is best known for her bas relief of President Franklin D. Roosevelt on the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C.[2] Her other work includes a bust of Duke Ellington, portraits of Mary McLeod Bethune and Booker T. Washington, and sculptures of John Brown (abolitionist) and President Calvin Coolidge.[3]

Selma Burke was born on December 31, 1900, in Mooresville, North Carolina, the seventh of 10 children of Neal and Mary Jackson Burke. Her father was an AME Church Minister.[4] As a child, she attended a one-room segregated schoolhouse.[3] Her interest in sculpting was ignited by her maternal grandmother, who was a painter, although her mother thought she should pursue a more marketable vocation.[5] Her father nurtured her interest in art by bringing home souvenirs and art objects from his international travels in Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean as an ocean liner chef.[5]

Burke attended Winston-Salem State University, and then graduated in 1924 from the St. Agnes Training School for Nurses in Raleigh. She moved to Harlem, where she found work as a private nurse.[4][6]

Burke became involved in the Harlem Renaissance during her marriage to Claude McKay. She worked for the Works Progress Administration and the Harlem Artists Guild, teaching art to children in Harlem. One of her WPA works, a bust of Booker T. Washington, was given to Frederick Douglass High School in Manhattan in 1936.[7]

In the late 1930s she traveled to Europe on a Rosenwald fellowship to study sculpture in Vienna and in Paris with Aristide Maillol. In 1940 she founded the Selma Burke School of Sculpture in New York City, finishing a Master of Fine Arts degree at Columbia University the following year.[4][8]

She was committed to teaching art; after teaching at her in New York City school, Burke opened the Selma Burke Art Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[2][9] Open from 1968 to 1981, the center "was an original art center that played an integral role in the Pittsburgh art community," offering courses ranging from studio workshops to puppetry classes.[10]

After competing in a national contest, Burke won a commission to sculpt a portrait honoring then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Four Freedoms. She created the sculpture based on sketches made during a 45-minute sitting with Roosevelt at the White House.[2] The 3.5-by-2.5-foot plaque was completed in 1944 and unveiled in September 1945 at the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C., where it still hangs today.[10] It is generally accepted, although not without some controversy, that John R. Sinnock's obverse design on the Roosevelt dime was based on Burke's plaque.[3][11][12][13] Sinnock later denied that Burke's portrait was an influence.[14][15]

Burke's other public sculpture pieces include a bust of Duke Ellington at the Performing Arts Center in Milwaukee, as well as works on display at the Hill House Center in Pittsburgh, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, Atlanta University, Spelman College, and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art.[16]

Selma Burke was among the artists featured at The National Urban League's inaugural exhibition at Gallery 62 in 1978.[17] Her last monumental work, created in 1980 when she was 80 years old, is a bronze statue of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Charlotte, N.C.[3]

Burke is an honorary member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority.[18] She received three honorary doctorate degrees during her lifetime, including one awarded by Livingston College in 1970.[3][4] Milton Shapp, then-governor of Pennsylvania, declared July 29, 1975, Selma Burke Day in recognition of the artist's contributions to art and education.[19]

Burke was a member of the first group of women – along with Louise Nevelson, Alice Neel, Georgia O'Keefe, and Isabel Bishop – to receive lifetime achievement awards from the Women's Caucus for Art, in 1979.[20] She received the award from President Jimmy Carter in a private ceremony in the Oval Office.[21][22] She received a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1983.[23]

Burke retired to New Hope, Pennsylvania, and died in 1995, at the age of 94.[3]

Bio found on: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selma_Burke

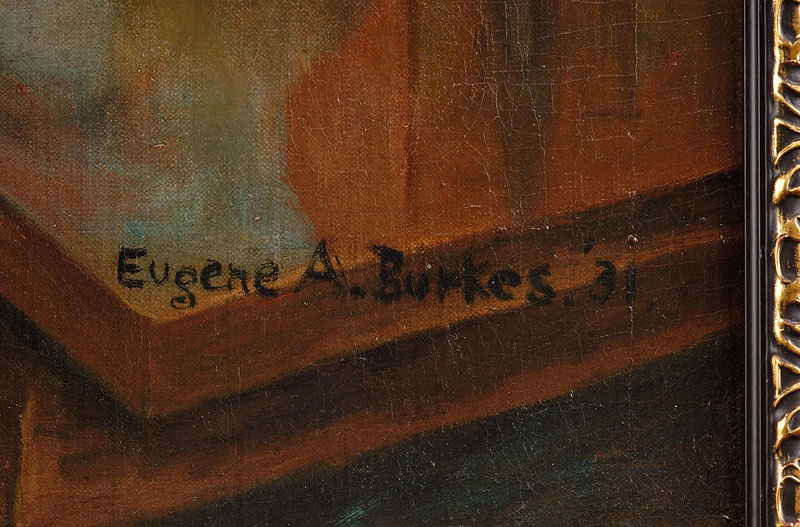

Eugene Alexander Burkes

Calvin Burnett (1921-2007)

Obituary By Bryan Marquard, Boston Globe Staff | October 12, 2007

As an artist and an art teacher, Calvin W. Burnett believed in knowing the rules and having the insight to break them.

"It's almost as though everything is right in relation to some aspect of whatever they happen to be doing," he said of his students in a 1980 oral history interview for the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art. "That is, any kind of line you draw with any kind of tool is right and good depending on what you are drawing. It's like there is no such thing as a good color or bad color or a correct color combination; it's only what you're trying to express with the color and what it's all about."

Proudly eclectic, he worked in many mediums, sometimes mixing one with another, and taught at the Massachusetts College of Art for 33 years. Mr. Burnett died Monday in Medway Country Manor nursing home of complications of Alzheimer's disease. He was 86 and had lived in Medway for three decades.

Writing in the Globe about a 1972 exhibition, Robert Taylor said Mr. Burnett's best pieces presented "the visual equivalent of the sound of Billie Holiday or Bessie Smith - a dark, indelible sorrow like the weight of an endless gloomy Sunday and, despite its burden, a determination to survive."

Mr. Burnett, Taylor wrote, "is essentially an artist who realizes his concepts graphically. Black, white, and half-tones of gray lend his angular, swooping line a mood of introversion."

From sketches to paintings, woodcuts, collage, and photographic elements, Mr. Burnett followed his muse down any avenue and felt a kinship with each approach. In the Smithsonian oral history, he called the interviewer's attention to the disparate styles of his work in the room where they were speaking.

"Just look around the room here," he said. "You see those things up there, and you see those things over there. They are very different from each other, and yet I love them both. I got a big bang out of doing them both, and I will continue to do them. And I do all sorts of things. And I think that's me. I wish what is me was something a good deal simpler, but it isn't, so tough!"

Torrey Burnett said her husband "enjoyed changing his style."

"The critics like to pigeonhole artists, but Cal wasn't like that," she said. "One year he'd be doing one thing,; the next he would be doing something completely different."

Born in Cambridge, Mr. Burnett was one of four children and grew up during the Great Depression, when his father's work as a physician afforded the family little financial security. Some patients were so poor that they paid his father with chickens or beans, Mr. Burnett told the Smithsonian.

"That may have been one of the reasons that none of the boys - there were three of us - wanted to follow in his footsteps," he said.

Not fond of school, Mr. Burnett found he had a talent for drawing, beginning with copying comic strips from the newspaper. He graduated from Cambridge High and Latin School and went to the Massachusetts College of Art.

"We were the young turks; we were the people who were going to change the world, you know," he said in the oral history of his college friends. "We wanted the latest in everything, you see. We'd read James Joyce, and . . . movies were important because they were the latest thing out. Jazz, of course, was terribly important at that time."

During World War II, Mr. Burnett worked in a shipyard because his eyesight was so poor he could not serve in the military. Afterward, he returned to the Massachusetts College of Art to train as a teacher. The experience, he said, illuminated the roles of the artist and the teacher and how one person sometimes could not be both.

"It's a big difference between the person who can teach somebody and the person who can do it," he said in the interview. "And there's no correlation between the person who can do it being able to tell another person how to do it. And I find that over at the art college all the time. There are people who are excellent artists who are terrible teachers."

Mr. Burnett also went to Boston University, where he received a master's in fine arts.

A few years after the war ended, he met Torrey Milligan. She had attended the Rhode Island School of Design and graduated from the Massachusetts College of Art. After knowing each other for about a decade, they married in 1960.

Romance between blacks and whites was less common at the time, "and they were predicting that because we were interracial our marriage wouldn't last," she said. "Well guess what? The others folded up, and ours lasted."

After they married, she became an art historian at the Massachusetts College of Art, where Mr. Burnett began teaching in the early 1950s.

Along with being part of private collections, Mr. Burnett's work is included in collections at the Smithsonian, and in Boston at the Museum of Fine Arts and the Museum of African-American History, his family said. He also published a book, "Objective Drawing Techniques."

As a teacher, Mr. Burnett emphasized to students what he called "discovery learning."

"You can't really make a mistake," he told the Smithsonian. "If an engineer builds a bridge wrong or a building, the thing will fall down and kill somebody. Or if a doctor makes a mistake, then of course somebody gets hurt. But if you are an artist trying to see how a pen works or a brush, all you have to do is take it and dip it in the ink and do it a million different ways."

In addition to his wife, Mr. Burnett leaves a daughter, Tobey of Leven, a village in East Yorkshire, England.

A memorial service will be held at 10 a.m. today in Community Church of West Medway.

© Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company.

Click here to listen to a 5 minute oral interview with Mr. Burnett

https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-calvin-burnett-11452

Father and Daughter

Collage and paint on board

14 1/4x20 inches

1976

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

A Girls Dream

Oil on board

22x26 inches

1947

Signed

Boy with Balloons

Oil on canvas

30x22 inches

Year unknown

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Edna

Linocut

6x3 1/3 inches

c. 1970

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

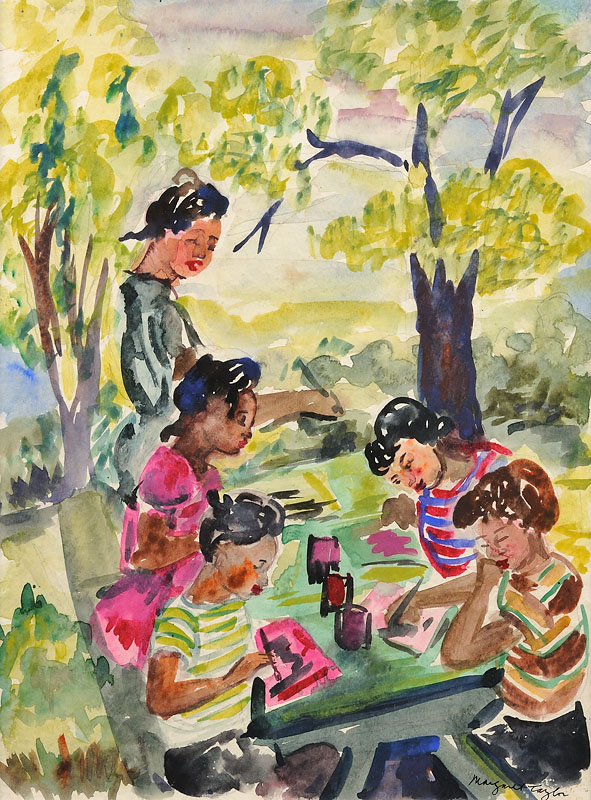

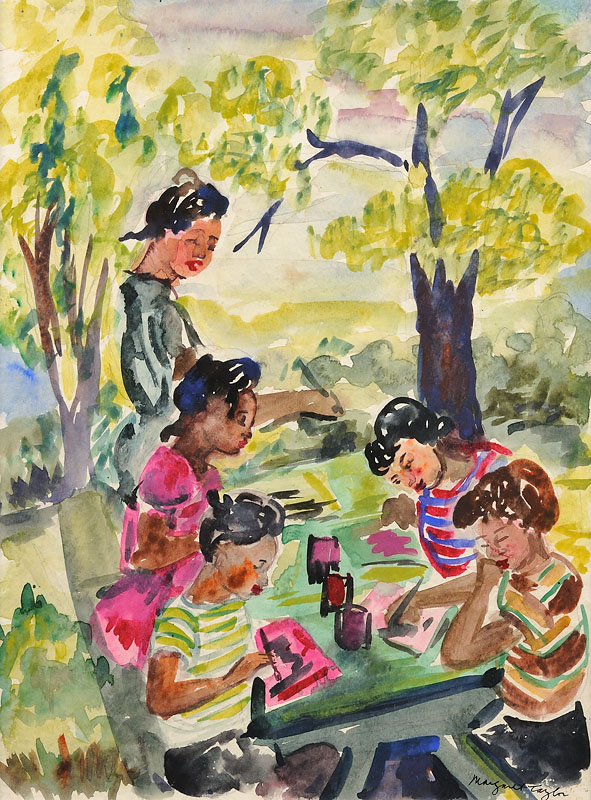

Margaret Burroughs (1917-2010)

Margaret Taylor-Burroughs (November 1, 1915[1][2] – November 21, 2010), was an American visual artist, writer, poet, educator, and arts organizer. She co-founded the Ebony Museum of Chicago, now the DuSable Museum of African American History. An active member of the African-American community, she also helped to establish the South Side Community Art Center, whose opening on May 1, 1941 [3] was dedicated by the First Lady of the United States Eleanor Roosevelt.[4]There at the age of 23 Burroughs served as the youngest member of its board of directors. She was a prolific writer, with her efforts directed toward the exploration of the Black experience and to children, especially to their appreciation of their cultural identity and to their introduction and growing awareness of art. She is also credited with the founding of Chicago's Lake Meadows Art Fair in the early 1950s.

Burroughs was born Victoria Margaret Taylor in St. Rose, Louisiana, where her father worked as a farmer and laborer at a railroad warehouse and her mother as a domestic. The family moved to Chicago in 1920 when she was five years old.[5]There she attended Englewood High School along with Gwendolyn Brooks, who in 1985-1986 served as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (now United States Poet Laureate). As classmates, the two joined the NAACP Youth Council. She earned teacher's certificates from Chicago Teachers College in 1937. She helped found the South Side Community Arts Center in 1939 to serve as a social center, gallery, and studio to showcase African American artists. In 1946, Taylor-Burroughs earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in art education from the School of the Art Institute of Chicagowhere she also earned her Master of Arts degree in art education, in 1948. Taylor-Burroughs married the artist Bernard Goss (1913–1966), in 1939, and they divorced in 1947. In 1949, she married Charles Gordon Burroughs and they remained married for 45 years until his death in 1994.[6]

Taylor-Burroughs taught at DuSable High School on Chicago's South side from 1946 to 1969, and from 1969 to 1979 was a professor of humanities at Kennedy-King College, a community college in Chicago. She also taught African American Art and Culture at Elmhurst College in 1968. She was named Chicago Park District Commissioner by Harold Washingtonin 1985, a position she held until 2010.

In one of Burroughs' linocuts, Birthday Party, both black and white children are seen celebrating. The black and white children are not isolated from each other; instead they are intermixed and mingling around the table together waiting for birthday cake.[12] An article published by The Art Institute of Chicago described Burroughs' Birthday Party and said, "Through her career, as both a visual artist and a writer, she has often chosen themes concerning family, community, and history. 'Art is communication,' she has said. 'I wish my art to speak not only for my people - but for all humanity.' This aim is achieved in Birthday Party, in which both black and white children dance, while mothers cut cake in a quintessential image of neighbors and family enjoying a special day together".[13] The painting puts in visual form Burroughs' philosophy that "the color of skin is a minor difference among men which has been stretched beyond its importance".[14]

Burroughs was impacted by Harriet Tubman, Gerard L. Lew, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and W.E.B. Du Bois. In Eugene Feldman’s The Birth and Building of the DuSable Museum Feldman writes about the influence Du Bois had on Burroughs’ life. He believes that Burroughs greatly admired Du Bois and writes that she campaigned to bring him to Chicago to lecture to audiences. Feldman wrote, “If we read about ‘cannabalistic and primitive Africa,’…It is a deliberate effort to put down a whole people and Dr. Du Bois fought this… Dr. Burroughs saw Dr. Du Bois and what he stood for and how he suffered himself to attain exposure of his views. She identified entirely with this important effort." Therefore, Burroughs clearly believed in Dr. Du Bois and the power of his message.[15]

In many of Burroughs' pieces, she depicts people with half black and half white faces. In The Faces of My People Burroughs carved five people staring at the viewer. One of the women is all black, three of the people are half black and half white and one is mostly white. While Burroughs is attempting to blend together the black and white communities, she also shows the barriers that stop the communities from uniting. None of the people in The Faces of My People are looking at each other, and this implies a sense of disconnect among them.[12] On another level, The Faces of My People deals with diversity. An article from the Collector magazine website describes Burroughs' attempts to unify in the picture. The article says, "Burroughs sees her art as a catalyst for bringing people together. This tableau of diverse individuals illustrates her commitment to mutual respect and understanding".[16]

Burroughs once again depicts faces that are half black and half white in My People. Even though the title is similar to the previously referenced piece, the woodcut has some differences. In this scene, there are four different faces – each of which is half white and half black. The head on the far left is tilted to the side and close to the head next to it. It seems as both heads are coming out of the same body – taking the idea of split personalities to the extreme. The women are all very close together, suggesting that they relate to each other. In The Faces of My People there were others pictured with different skin tones, but in My People all of the people have the same half black and half white split. Therefore, My People focuses on a common conflict that all the women in the picture face.

Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Taylor-Burroughs

Manchild

Lithograph

14x9 3/4 inches

1986

Signed and dated

Numbered (8/18)

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Mexican Girl

Linocut

18 3/4x 16 inches

1953

Signed and dated

Numbered (5/5)

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

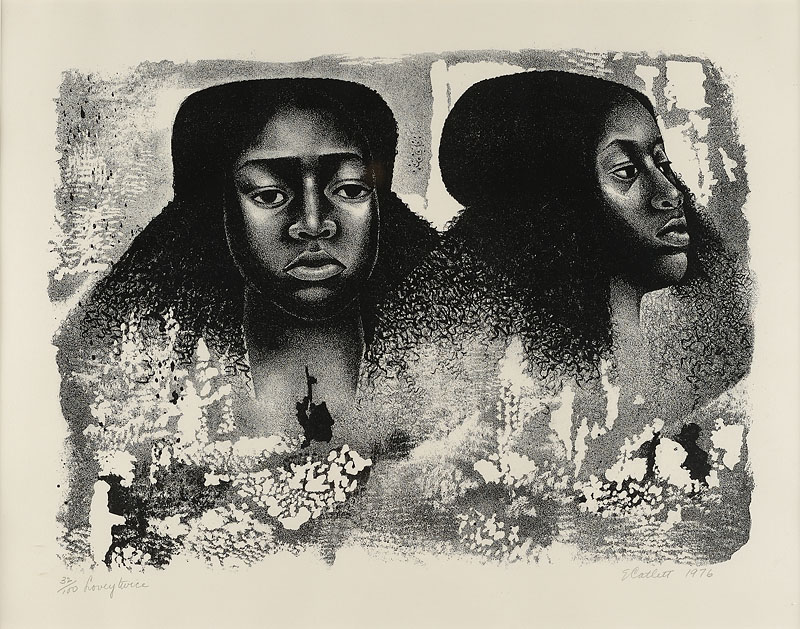

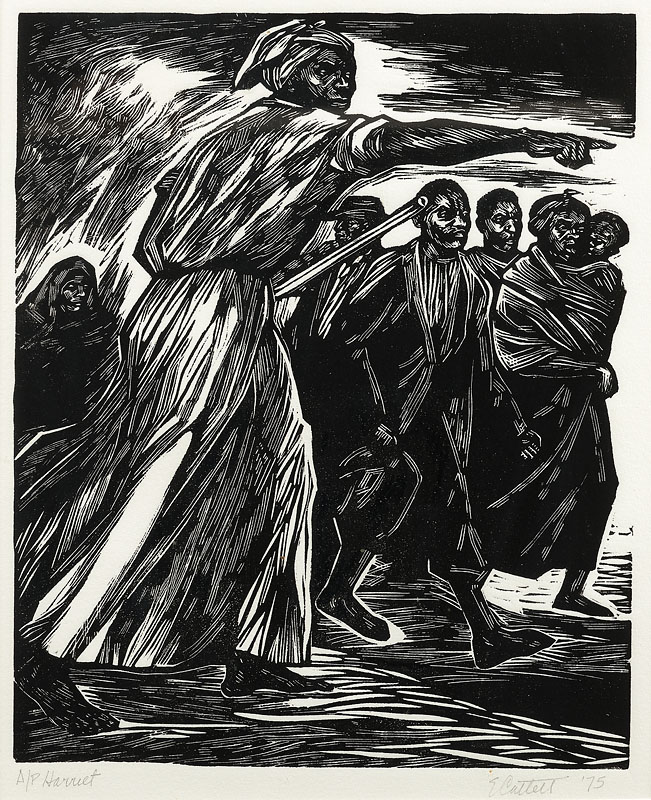

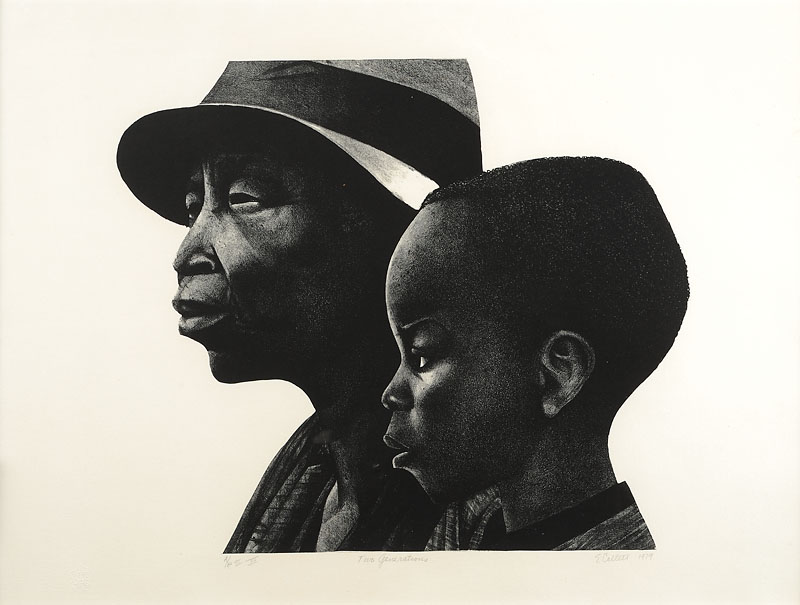

Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012)

Elizabeth Catlett (April 15, 1915[2] – April 2, 2012)[3] was an African-American graphic artist and sculptor best known for her depictions of the African-American experience in the 20th century, which often had the female experience as their focus. She was born and raised in Washington, D.C. to parents working in education, and was the grandchild of freed slaves. It was difficult for a black woman in this time to pursue a career as a working artist. Catlett devoted much of her career to teaching. However, a fellowship, awarded to her in 1946, allowed her to travel to Mexico City, where she would work with the Taller de Gráfica Popular for twenty years and become the head of the sculpture department for the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas. In the 1950s, her main means of artistic expression shifted from print to sculpture, though she would never give up the former.

Her work is a mixture of abstract and figurative in the Modernist tradition, with influence from African and Mexican arttraditions. According to the artist, the main purpose of her work is to convey social messages rather than pure aesthetics. While not very well known to the general public, her work is heavily studied by art students looking to depict race, gender and class issues. During her lifetime, Catlett received many awards and recognitions including membership in the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana, the Art Institute of Chicago Legends and Legacy Award, honorary doctorates from Pace University and Carnegie Mellon and the International Sculpture Center's Lifetime Achievement Award in contemporary sculpture.

Catlett was born and raised in Washington, DC.[3][4] Both her mother and her father were the children of freed slaves, and her grandmother told her stories about the capture of blacks in Africa and the hardships of plantation life.[4][5][6] She was the youngest of three children. Both parents worked in education. Her mother was a truant officer and her father taught at Tuskegee University then at the DC public school system.[2] Her father died before she was born, leaving her mother to hold several jobs to support the household.[2][4][6]

Her interest in art began early. As a child she became fascinated by a wood carving of a bird that her father made. In high school, she studied art with a descendant of Frederick Douglass.[5]