Oliver Wendell Harrington (1912-1995)

Oliver Wendell "Ollie" Harrington (February 14, 1912 – November 2, 1995) was an American cartoonist and an outspoken advocate against racism and for civil rights in the United States. Of multi-ethnic descent, Langston Hughescalled him "America's greatest African-American cartoonist".[1] Harrington requested political asylum in East Germany in 1961; he lived in Berlin for the last three decades of his life.

Born to Herbert and Euzsenie Turat Harrington in Valhalla, New York, Harrington was the oldest of five children. He began cartooning to vent his frustrations about a viciously racist sixth grade teacher and graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School in 1929. Immersing himself in the Harlem Renaissance, Harrington found employment when Ted Poston, city editor for the Amsterdam News became aware of Harrington's already considerable skills as a cartoonist and political satirist.

In 1935, Harrington created Dark Laughter, a regular single panel cartoon, for that publication. The strip was later retitled Bootsie, after its most famous character, an ordinary African American dealing with racism in the U.S. Harrington described him as "a jolly, rather well-fed but soulful character." During this period, Harrington enrolled in Fine Arts at Yale University to complete his degree, but could not finish because of the United States entry into World War II.

On October 18, 1941, he started publication of Jive Gray (1941–1951), a weekly adventure comic strip about an eponymous African-American aviator; the strip went on until Harrington moved to Paris.

During World War II, the Pittsburgh Courier sent Harrington as a correspondent to Europe and North Africa. In Italy, he met Walter White, executive secretary of the NAACP. After the war, White hired Harrington to develop the organization's public relations department, where he became a visible and outspoken advocate for civil rights.

In that capacity, Harrington published "Terror in Tennessee," a controversial expose of increased lynching violence in the post-W.W. II South. Given the publicity garnered by his sensational critique, Harrington was invited to debate with U.S. Attorney General Tom C. Clark on the topic of "The Struggle for Justice as a World Force." He confronted Clark for the U.S. government's failure to curb lynching and other racially motivated violence.

In 1947 Harrington left the NAACP and returned to cartooning. In the postwar period his prominence and social activism brought him scrutiny from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the House Un-American Activities Committee. Hoping to avoid further government scrutiny, Harrington moved to Paris in 1951. In Paris, Harrington joined a thriving community of African-American expatriate writers and artists, including James Baldwin, Chester Himes, and Richard Wright, who became a close friend.

Harrington was shaken by Wright's death in 1960, suspecting that he was assassinated. He thought that the American embassy had a deliberate campaign of harassment directed toward the expatriates. In 1961 he requested political asylum in East Germany.[2] He spent the rest of his life in East Berlin, finding plentiful work and a cult following. He illustrated and contributed to publications such as Eulenspiegel, Das Magazine, and the Daily Worker.

Bio courtesy of Wikipidia. Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ollie_Harrington

Statue of "Liberty"

Pencil and crayon on paper

13x19 1/2 inches

1942

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

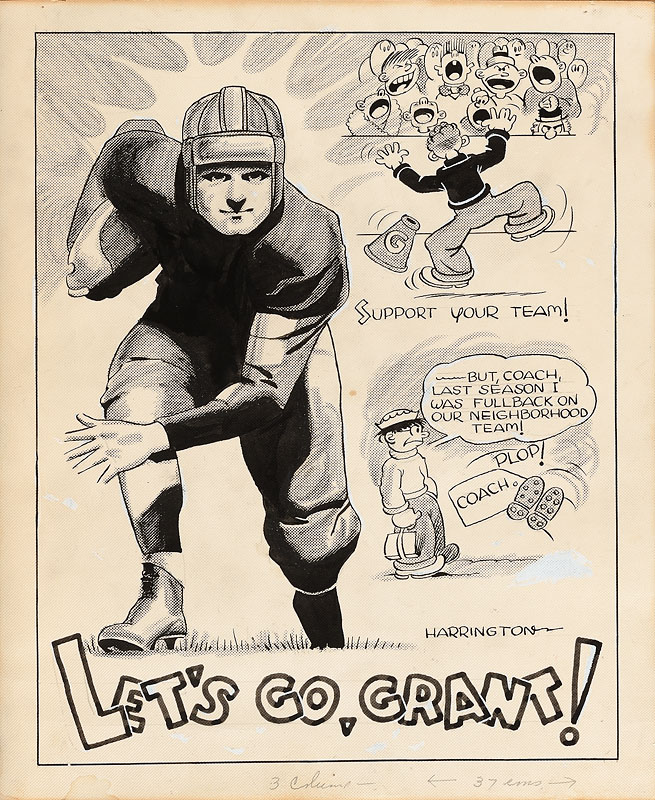

Lets Go Giant

Reproduction technique with hand retouching

15x3/4x12 1/4 inches

c. 1940

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio