Alan Randall Freelon (1895-1960)

Allan Randall Freelon, Sr. (September 2, 1895 – August 6, 1960),[1] a native of Philadelphia, US, was an African American artist, educator and civil rights activist. He is best known as an African American Impressionist-style painter during the time of the Harlem Renaissance and as the first African American to be appointed art supervisor of the Philadelphia School District.

Born in Philadelphia on September 2, 1895, to Douglas Freelon and Laura E. (Goodwin) Freelon,[2] a "middle-class family of notable academic achievement",[3] Freelon was the oldest of three children. On September 4, 1918, he married Marie J. Cuyjet,[4] and they had one child, Allan Randall Freelon, Jr. At some point Freelon and Cuyjet divorced; Freelon was married to Mary Kouzmanoff at the time of his death, August 6, 1960. He died while at his art studio in Telford, Pennsylvania.[5] Architect Philip Freelon is his grandson.[6]

Freelon attended the South Philadelphia High School for Boys, followed by a four-year scholarship (1912–1916) to the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art,[6] from which he graduated in 1916 with a diploma in normal art instruction (what would be called art education today). From there he attended the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy,[7] an upper division of Central High School created to prepare men for teaching careers. Following a stint in the Army from 1917 to 1919, where he served as a second lieutenant,[2] he attended the University of Pennsylvania and graduated in February 1924 with a BS in education. Further studies ensued at the Barnes Foundation (1927 through 1929),[8] followed by private studies with Emile Gruppe, modernist Earl Horter (1881–1940), neo-Impressionist Hugh Breckenridge (1870–1937), and printmaker Dox Thrash (1892–1965),[2] and the earning of an MFA in 1943[9] from Tyler School of Art of Temple University.

One of Freelon's earliest documented exhibitions also happened to be the first exhibition of African-American art in Harlem, at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library,[10] now part of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. He later exhibited from 1928 to 1932 and in 1934 with the William E. Harmon Foundation,[2] whose exhibitions traveled widely in the United States. Other exhibition venues included the Albright-Knox Gallery (Buffalo, NY), the National Gallery of Art(Washington, DC), Howard University Gallery of Art (Washington, DC), New Jersey State Museum (Trenton, NJ), Arthur U. Newton Gallery (New York, NY), Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY), Lincoln University,[11] and Lehigh Art Alliance (Lehigh, PA).[2]

Freelon was one of seven African-American artists who participated in the exhibition Art Commentary on Lynching, organized by the NAACP in response to deaths such as that of Claude Neal. The exhibition was held February 15 to March 2, 1935, in New York. Freelon's work, Barbecue – American Style, portrays a naked man, tortured and in flames, encircled by the feet of spectators.[12][13] He wrote:

I have not attempted to portray any particular lynching, but merely to record the horror of what has come to be a major sports event...[13]

Freelon was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, Philadelphia Art Teachers Association, Philadelphia Art Week Association,[8] Artists' Equity, Tra Club, Pyramid Club,[10] Society of New Jersey Artists,[14] North Shore Art Association of Gloucester, MA, American Federation of Arts,[8] and was the first person of color elected to the Print Club of Philadelphia.[15]

Formed in 1937, the Pyramid Club provided prominent African Americans, who were excluded from most clubs, with opportunities to meet and network.[16][17] From March 2–16, 1941, the Pyramid Club sponsored the first of its annual invitational art exhibits, 20th Century Negro Contemporary Artists and Memorial Paintings of Henry O. Tanner.[18][19] Freelon was asked to speak at the inaugural event, and discussed the role of the Black artist and his influence in current events.[10]

Coming of artistic age during the time of the "New Negro", Freelon found himself in aesthetic disagreement with fellow Philadelphian Alain LeRoy Locke, who urged African American artists to take up African themes as the source for their art in The New Negro (NY: Boni, 1925). Freelon "vigorously defended the artist's right to freedom of expression",[2] writing in a 1944 review[20] of James A. Porter's book, Modern Negro Art:

In his chapter on the "New Negro" movement, Mr. Porter analyzes that most interesting and fecund period of the late twenties, when opposite schools of thought were attempting to direct the Negro artist into this "African background," or insisting that he be accorded the same freedom of choice as that granted any other artist as regards subject matter and means of expression. The author dispassionately evaluates both theories and his conclusions are valid and sound. He brands the "African background" theory for what it was: propaganda.

Following his 1919 graduation from the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy,[2] Freelon became an art teacher in the Philadelphia public school system. In 1921 he was appointed as assistant director of art education, the first African American to be appointed to the district's Department of Superintendence.[8] In July 1939 he was named "special assistant to Theodore M. Dilliway [sic: Dillaway], director of art in the Philadelphia public schools, and will supervise art work in vocational and junior high schools. He has been supervising art projects in the elementary schools for a number of years, and his promotion follows competitive examination for the new post, held recently by Board of Education."[21] He placed first in that examination[22] and held that position until his death. Deeply interested in printmaking, Freelon taught etching and lithography at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from 1940 to 1946.[14]

Bio courtesy of Wikipidia. Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allan_Randall_Freelon

Untitled (Harbor)

Oil on board

8x10 inches

c. 1940

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

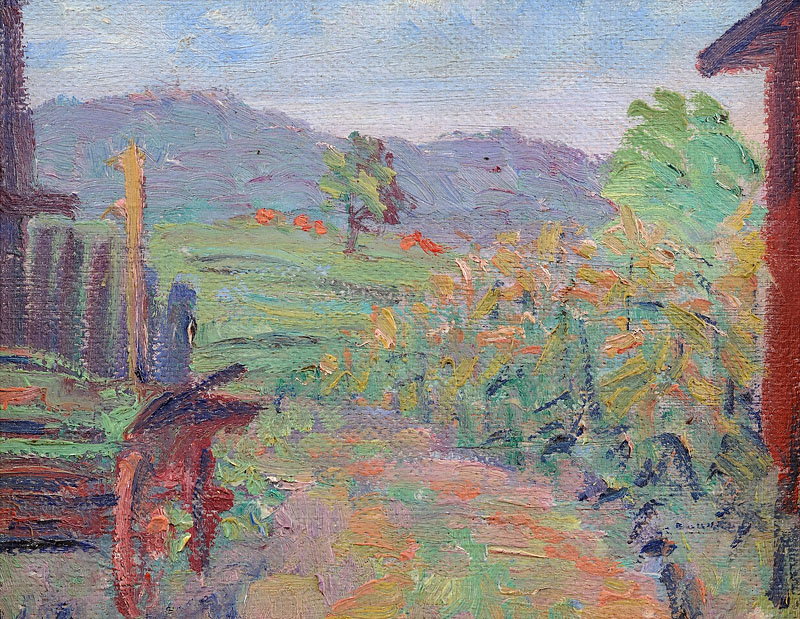

Untitled (Landscape)

Oil on board

7 1/2x9 1/2 inches

Year unknown

Not signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Untitled (Sheep Grazing)

Oil on board

7 1/2x9 1/2 inches

Year unknown

Not signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio