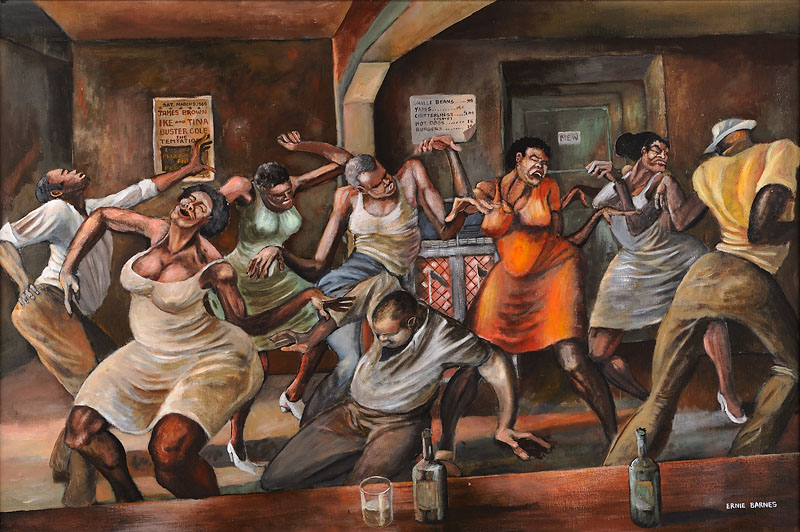

Ernie Barnes (1938-2009)

Ernest Eugene Barnes, Jr. (July 15, 1938 – April 27, 2009) was an African-American painter, well known for his unique style of elongation and movement. He was also a professional football player, actor and author.

Ernest Barnes, Jr. was born during Jim Crow in "the bottom" community of Durham, North Carolina, near the Hayti District of the city. His father, Ernest E. Barnes, Sr. (1899–1966) worked as a shipping clerk for Liggett Myers Tobacco Company in Durham. His mother, Fannie Mae Geer (1905–2004) oversaw the household staff for prominent Durham attorney and local Board of Education member Frank L. Fuller, Jr.

On days when Fannie allowed "June" (Barnes' nickname to family and childhood friends) to accompany her to the Fuller home, Barnes had the opportunity to peruse the art books and listen to classical music. The young Ernest was intrigued and captivated by the works of master artists. By the time Barnes entered the first grade, he was familiar with the works of such masters as Toulouse-Lautrec, Delacroix, Velasquez, Rubens, and Michelangelo. When he entered junior high, he could appreciate, as well as decode, many of the cherished masterpieces within the walls of mainstream museums – although it would be a half dozen more years before he was allowed entrance because of his race.[1]

A self-described chubby and unathletic child, Barnes was taunted and bullied by classmates. He continually sought refuge in his sketchbooks, hiding in the less-traveled parts of campus away from other students. One day in a quiet area, Ernest was found drawing in a notebook by the masonry teacher, Tommy Tucker, who was also the weightlifting coach and a former athlete. Tucker was intrigued with Barnes' drawings so he asked the aspiring artist about his grades and goals. Tucker shared his own experience of how bodybuilding improved his strength and outlook on life. That one encounter would begin Barnes' discipline and dedication that would permeate his life. In his senior year at Hillside High School, Barnes became the captain of the football team and state champion in the shot put.[2]

In 1956 Barnes graduated from Hillside High School with 26 athletic scholarship offers. Segregation prevented him from attending nearby Duke or the University of North Carolina. His mother promised him a car if he lived at home, so he chose North Carolina College at Durham (formerly North Carolina College for Negroes, now North Carolina Central University). He majored in art on a full athletic scholarship. His college track coach was the famed Dr. Leroy T. Walker.[1] Barnes played the football positions of tackle and center at NCC at Durham.

At age 18, on a college art class field trip to the newly desegregated North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, Barnes inquired where he could find "paintings by Negro artists." The docent responded, "Your people don't express themselves that way."[3] Poetic justice prevailed 23 years later in 1979 when Barnes returned to the museum for a solo exhibition, hosted by North Carolina Governor James Hunt.

In 1990 Barnes was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts by North Carolina Central University.

In 1993 Barnes was selected to the "Black College Football 100th Year All-Time Team" by the Sheridan Broadcasting Network.[4]

In 1999 Barnes was bestowed "The University Award", the highest honor by The University of North Carolina Board of Governors.[5]

In December 1959 Barnes was drafted in the 10th round by the then-World Champion Baltimore Colts. He was originally selected in the 8th-round by the Washington Redskins,[6] who renounced the pick minutes after discovering he was a Negro.

Shortly after his 22nd birthday, while at the Colts training camp, Barnes was interviewed by N.P. Clark, sportswriter for the Baltimore News-Post newspaper. Until then Barnes was always known by his birth name, Ernest Barnes. But when Clark's article appeared on July 20, 1960, it referred to him as "Ernie Barnes," which changed his name and life forever.[7]

Barnes credits his college art instructor Ed Wilson for laying the foundation for his development as an artist. Wilson was a sculptor who instructed Barnes to paint from his own life experiences. "He made me conscious of the fact that the artist who is useful to America is one who studies his own life and records it through the medium of art, manners and customs of his own experiences."[18]

All his life, Barnes was ambivalent about his football experience. In interviews and in personal appearances, Barnes said he hated the violence and the physical torment of the sport. However, his years as an athlete gave him unique, in-depth observations. "(Wilson) told me to pay attention to what my body felt like in movement. Within that elongation, there's a feeling. And attitude and expression. I hate to think had I not played sports what my work would look like."[19]

Barnes' first painting sale was in 1959 for $90 to Boston Celtic Sam Jones for a painting called Slow Dance.[1] It was subsequently lost in a fire at Jones' home.

Critics have defined Barnes' work as neo-mannerist.[20] Based on his signature use of serpentine lines, elongation of the human figure, clarity of line, unusual spatial relationships, painted frames, and distinctive color palettes, art critic Frank Getlein credited Barnes as the founder of the neo-Mannerism movement - because of the similarity of technique and composition prevalent during the 16th century, as practiced by such masters as Michelangelo and Raphael.[21]

Numerous artists have been influenced by Barnes' art and unique style. Accordingly, several copyright infringement lawsuits have been settled and are currently pending.

Ernie Barnes framed his paintings with distressed wood in homage to his father. In his 1995 autobiography, artist Ernie Barnes wrote of his father: “... with so little education, he had worked so hard for us. His legacy to me was his effort, and that was plenty. He knew absolutely nothing about art.”[1]

Weeks before Ernie Barnes’ first solo art exhibition in 1966, he was at the family home in Durham, North Carolina as his father lay in the hospital after suffering a stroke. He noticed the usually well-maintained white picketed fence had gone untended since his father’s illness. Days later, Ernest E. Barnes, Sr. died. “I placed a painting against the fence and stood away and had a look. I was startled at the marriage between the old wood fence and the painting. It was perfect. In tribute, Daddy’s fence would hug all my paintings in a prestigious New York gallery. That would have made him smile.”[1]

A consistent and distinct feature in Barnes' work is the closed eyes of his subjects. "It was in 1971 when I conceived the idea of The Beauty of the Ghetto as an exhibition. And I exposed it to some people who were black to get a reaction. And from one (person) it was very negative. And when I began to express my points of view (to this) professional man, he resisted the notion. And as a result of his comments and his attitude I began to see, observe, how blind we are to one another's humanity. Blinded by a lot of things that have, perhaps, initiated feelings in that light. We don't see into the depths of our interconnection. The gifts, the strength and potential within other human beings. We stop at color quite often. So one of the things we have to be aware of is who we are in order to have the capacity to like others. But when you cannot visualize the offerings of another human being you're obviously not looking at the human being with open eyes."[22] "We look upon each other and decide immediately: This person is black, so he must be... This person lives in poverty, so he must be..."[13]

Barnes died on April 27, 2009 at Cedars Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, California from blood cancer.[46] He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in Durham, North Carolina near the site of where his family home once stood, and at the beach in Carmel, California, one of his favorite cities.

Link to the full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernie_Barnes

Dance Hall

Oil on board

24x36 inches

1969

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Slam Dunk

Acrylic on canvas

60x27 inches

c.1970

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio