Calvin Burnett (1921-2007)

Obituary By Bryan Marquard, Boston Globe Staff | October 12, 2007

As an artist and an art teacher, Calvin W. Burnett believed in knowing the rules and having the insight to break them.

"It's almost as though everything is right in relation to some aspect of whatever they happen to be doing," he said of his students in a 1980 oral history interview for the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art. "That is, any kind of line you draw with any kind of tool is right and good depending on what you are drawing. It's like there is no such thing as a good color or bad color or a correct color combination; it's only what you're trying to express with the color and what it's all about."

Proudly eclectic, he worked in many mediums, sometimes mixing one with another, and taught at the Massachusetts College of Art for 33 years. Mr. Burnett died Monday in Medway Country Manor nursing home of complications of Alzheimer's disease. He was 86 and had lived in Medway for three decades.

Writing in the Globe about a 1972 exhibition, Robert Taylor said Mr. Burnett's best pieces presented "the visual equivalent of the sound of Billie Holiday or Bessie Smith - a dark, indelible sorrow like the weight of an endless gloomy Sunday and, despite its burden, a determination to survive."

Mr. Burnett, Taylor wrote, "is essentially an artist who realizes his concepts graphically. Black, white, and half-tones of gray lend his angular, swooping line a mood of introversion."

From sketches to paintings, woodcuts, collage, and photographic elements, Mr. Burnett followed his muse down any avenue and felt a kinship with each approach. In the Smithsonian oral history, he called the interviewer's attention to the disparate styles of his work in the room where they were speaking.

"Just look around the room here," he said. "You see those things up there, and you see those things over there. They are very different from each other, and yet I love them both. I got a big bang out of doing them both, and I will continue to do them. And I do all sorts of things. And I think that's me. I wish what is me was something a good deal simpler, but it isn't, so tough!"

Torrey Burnett said her husband "enjoyed changing his style."

"The critics like to pigeonhole artists, but Cal wasn't like that," she said. "One year he'd be doing one thing,; the next he would be doing something completely different."

Born in Cambridge, Mr. Burnett was one of four children and grew up during the Great Depression, when his father's work as a physician afforded the family little financial security. Some patients were so poor that they paid his father with chickens or beans, Mr. Burnett told the Smithsonian.

"That may have been one of the reasons that none of the boys - there were three of us - wanted to follow in his footsteps," he said.

Not fond of school, Mr. Burnett found he had a talent for drawing, beginning with copying comic strips from the newspaper. He graduated from Cambridge High and Latin School and went to the Massachusetts College of Art.

"We were the young turks; we were the people who were going to change the world, you know," he said in the oral history of his college friends. "We wanted the latest in everything, you see. We'd read James Joyce, and . . . movies were important because they were the latest thing out. Jazz, of course, was terribly important at that time."

During World War II, Mr. Burnett worked in a shipyard because his eyesight was so poor he could not serve in the military. Afterward, he returned to the Massachusetts College of Art to train as a teacher. The experience, he said, illuminated the roles of the artist and the teacher and how one person sometimes could not be both.

"It's a big difference between the person who can teach somebody and the person who can do it," he said in the interview. "And there's no correlation between the person who can do it being able to tell another person how to do it. And I find that over at the art college all the time. There are people who are excellent artists who are terrible teachers."

Mr. Burnett also went to Boston University, where he received a master's in fine arts.

A few years after the war ended, he met Torrey Milligan. She had attended the Rhode Island School of Design and graduated from the Massachusetts College of Art. After knowing each other for about a decade, they married in 1960.

Romance between blacks and whites was less common at the time, "and they were predicting that because we were interracial our marriage wouldn't last," she said. "Well guess what? The others folded up, and ours lasted."

After they married, she became an art historian at the Massachusetts College of Art, where Mr. Burnett began teaching in the early 1950s.

Along with being part of private collections, Mr. Burnett's work is included in collections at the Smithsonian, and in Boston at the Museum of Fine Arts and the Museum of African-American History, his family said. He also published a book, "Objective Drawing Techniques."

As a teacher, Mr. Burnett emphasized to students what he called "discovery learning."

"You can't really make a mistake," he told the Smithsonian. "If an engineer builds a bridge wrong or a building, the thing will fall down and kill somebody. Or if a doctor makes a mistake, then of course somebody gets hurt. But if you are an artist trying to see how a pen works or a brush, all you have to do is take it and dip it in the ink and do it a million different ways."

In addition to his wife, Mr. Burnett leaves a daughter, Tobey of Leven, a village in East Yorkshire, England.

A memorial service will be held at 10 a.m. today in Community Church of West Medway.

© Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company.

Click here to listen to a 5 minute oral interview with Mr. Burnett

https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-calvin-burnett-11452

Father and Daughter

Collage and paint on board

14 1/4x20 inches

1976

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

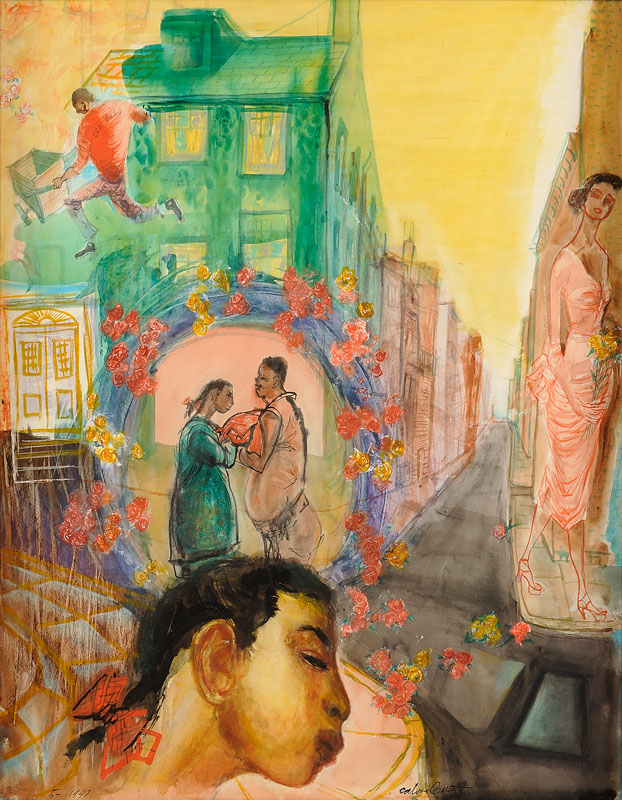

A Girls Dream

Oil on board

22x26 inches

1947

Signed

Boy with Balloons

Oil on canvas

30x22 inches

Year unknown

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Edna

Linocut

6x3 1/3 inches

c. 1970

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio