Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012)

Elizabeth Catlett (April 15, 1915[2] – April 2, 2012)[3] was an African-American graphic artist and sculptor best known for her depictions of the African-American experience in the 20th century, which often had the female experience as their focus. She was born and raised in Washington, D.C. to parents working in education, and was the grandchild of freed slaves. It was difficult for a black woman in this time to pursue a career as a working artist. Catlett devoted much of her career to teaching. However, a fellowship, awarded to her in 1946, allowed her to travel to Mexico City, where she would work with the Taller de Gráfica Popular for twenty years and become the head of the sculpture department for the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas. In the 1950s, her main means of artistic expression shifted from print to sculpture, though she would never give up the former.

Her work is a mixture of abstract and figurative in the Modernist tradition, with influence from African and Mexican arttraditions. According to the artist, the main purpose of her work is to convey social messages rather than pure aesthetics. While not very well known to the general public, her work is heavily studied by art students looking to depict race, gender and class issues. During her lifetime, Catlett received many awards and recognitions including membership in the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana, the Art Institute of Chicago Legends and Legacy Award, honorary doctorates from Pace University and Carnegie Mellon and the International Sculpture Center's Lifetime Achievement Award in contemporary sculpture.

Catlett was born and raised in Washington, DC.[3][4] Both her mother and her father were the children of freed slaves, and her grandmother told her stories about the capture of blacks in Africa and the hardships of plantation life.[4][5][6] She was the youngest of three children. Both parents worked in education. Her mother was a truant officer and her father taught at Tuskegee University then at the DC public school system.[2] Her father died before she was born, leaving her mother to hold several jobs to support the household.[2][4][6]

Her interest in art began early. As a child she became fascinated by a wood carving of a bird that her father made. In high school, she studied art with a descendant of Frederick Douglass.[5]

Catlett did her undergraduate studies at Howard University, graduating cum laude, although it was not her first choice.[2][7] She was also admitted into the Carnegie Institute of Technology but was refused admission when the school discovered she was black.[2][4] But in 2007, as Cathy Shannon of E&S Gallery was giving a talk to a youth group at the August Wilson Center for African American Culture in Pittsburgh, PA, she recounted Catlett's tie to Pittsburgh because of this injustice. An administrator with Carnegie Mellon University was in the audience and heard the story for the first time. She immediately told the story to the school's president, Jared Leigh Cohon, who was unaware of it as well and deeply appalled that such a thing had happened. In 2008, President Cohon presented Catlett with an honorary Doctorate degree and a one-woman show of her art was presented by E&S Gallery at The Regina Gouger Miller Gallery on the campus of Carnegie Mellon University.[8]

While at Howard University, Catlett's professors included artist Lois Mailou Jones and philosopher Alain Locke.[4] She also came to know artists James Herring, James Wells, and future art historian James A. Porter.[5][9] Her tuition was paid for by her mother's savings and scholarships that the artist earned, and she graduated with honors in 1937.[1][2][3][4] At the time, the idea of a career as an artist for blacks was far-fetched, so she did her undergraduate studies with the aim of being a teacher.[5] After graduation, she moved to her mother's hometown of Durham, NC to teach high school.[2][5]

Because Catlett became interested in the work of landscape artist Grant Wood, she entered the graduate program of the University of Iowa.[2] There, she studied drawing and painting with Wood, as well as sculpture with Henry Stinson.[10] Wood advised her to depict images of what she knew best, so Catlett began sculpting images of African-American women and children.[2][11][12] However, despite being accepted to the school, she was not permitted to stay in the dormitories, requiring her to rent a room off-campus.[10] One of her roommates was future novelist and poet Margaret Walker.[5] Catlett graduated in 1940, one of three to earn the first masters in fine arts from the university, and the first African-American woman to receive the degree.[1][3][10] Later in life, Catlett donated money to the university to fund the Elizabeth Catlett Mora Scholarship Fund, which supports African-American and Latino students studying printmaking.[10]

After Iowa, Catlett moved to New Orleans to work at Dillard University, spending the summer breaks in Chicago. During her summers, she studied ceramics at the Art Institute of Chicago and lithography at the South Side Community Art Center.[3][9][12] In Chicago, she also met her first husband, artist Charles Wilbert White. The couple married in 1941.[3][5][13] In 1942, the couple moved to New York, where Catlett taught adult education classes at the George Washington Carver School in Harlem. She also studied lithography at the Art Students League of New York, and received private instruction from Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine,[3][9][12] who urged her to add abstract elements to her figurative work.[2] During her time in New York, she met intellectuals and artists such as Gwendolyn Bennet, W.E.B. Dubois, Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglass, and Paul Robeson.[5][6]

In 1946, Catlett received a Rosenwald Fund Fellowship to travel with her husband to Mexico and study.[4][12] She accepted the grant in part because at the time American art was trending toward the abstract while she was interested in art related to social themes.[5] Shortly after moving to Mexico that same year, Catlett divorced White.[13] In 1947, she entered the Taller de Gráfica Popular, a workshop dedicated to graphic promoting leftist social causes and education. There she met printmaker and muralist Francisco Mora, whom she married in the same year.[3][9][13] The couple had three children, all of whom developed careers in the arts: Francisco in jazz music, Juan in filmmaking and David in the visual arts. The last worked as his mother's assistant doing the heavy aspects of sculpting when she no longer could.[5][6][14]In 1948, she entered the Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado "La Esmeralda" to study wood sculpture with José L. Ruíz and ceramic sculpture with Francisco Zúñiga.[3][12] During this time in Mexico, she became more serious about her art and more dedicated to the work it demanded.[9] She also met Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and David Alfaro Siqueiros .[6]

She worked with the Taller until 1966. However, the fact that a number of its members were Communist Party members, along with her political activism, which had led to an arrest in 1949 while protesting during a railroad strike in Mexico City, Catlett came under surveillance by the US embassy.[2][13][15] Eventually, she was barred from entering the United States and declared an "undesirable alien," and was unable to return home to visit her ill mother before her parent died.[5] In 1962, she renounced her American citizenship and became a Mexican citizen.[2][3][9]

In 1971, after a letter-writing campaign to the State Department by colleagues and friends, she was issued a special permit to attend an exhibition of her work at the Studio Museum in Harlem.[2][5]

After retiring from her teaching position at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, she moved to the city of Cuernavaca, Morelos in 1975.[2] In 1983, she and Mora bought an apartment in Battery Park City, NY, where from then until Mora's death in 2002, the couple spent part of the year.[2][6][13] Catlett regained her American citizenship in 2002.[6][9]

Catlett is recognized primarily for sculpting and print work.[3] Her sculptures are known for being provocative but her prints are more widely recognized, mostly because of her work with the Taller de Gráfica Popular.[3][5] Although she never left printmaking, starting in the 1950s, she shifted primarily to sculpture.[13] Her printwork was mostly woodcuts and linocuts with sculptures made of a variety of materials such as clay, cedar, mahogany, eucalyptus, marble, limestone, onyx, bronze, and Mexican stone (cantera).[2][9] She often recreated the same piece in several different media.[14] Sculptures range in size and scope from small wood figures inches high to others several feet tall to monumental works for public squares and gardens. This latter category includes a 10.5-foot sculpture of Louis Armstrong in New Orleans and a 7.5-foot work depicting Sojourner Truth in Sacramento.[5]

Much of her work is realistic and highly stylized two- or three-dimensional figures,[4] applying the Modernist principles (such as organic abstraction to create a simplified iconography to display human emotions) of Henry Moore, Constantin Brancusi and Ossip Zadkine to popular and easily recognized imagery. Other major influences include African and pre-Hispanic Mexican art traditions. Her works do not explore individual personalities – not even those of historical figures. Instead, they convey abstracted and generalized ideas and feelings.[13] Her imagery arises from a scrupulously honest dialogue with herself on her life and perceptions, and between herself and "the other", that is, contemporary society's beliefs and practices of racism, classism and sexism.[21] Many young artists study her work as a model for themes relating to gender, race and class, but she is relatively unknown to the general public.[15]

Her work revolved around themes such as social injustice, the human condition, historical figures, women and the relationship between mother and child.[13] These themes were specifically related to the African-American experience in the 20th century with some influence from Mexican reality.[1][2][9] This focus began while she was at the University of Iowa, where she was encouraged to depict what she knew best. Her thesis was the sculpture Mother and Child (1939), which won first prize at the American Negro Exposition in Chicago in 1940.[11][12]

Her subjects range from sensitive maternal images to confrontational symbols of Black Power, and portraits of Martin Luther King, Jr., Harriet Tubman and writer Phyllis Wheatley,[4][14] as she believed that art can play a role the construction of transnational and ethnic identity.[12] Her best-known works depict black women as strong and maternal.[2][15] The women are voluptuous, with broad hips and shoulders, in positions of power and confidence, often with torsos thrust forward to show attitude. Faces tend to be mask-like, generally upturned.[5] Mother and Child (1939) shows a young woman with very short hair and features similar to that of a Gabon mask. A late work Bather (2009) has a similar subject flexing her triceps.[2] Her linocut series The Black Woman Speaks, is among the first graphic series in Western art to depict the image of the American black woman as a heroic and complex human being.[21]:46 Her work was influenced by the Harlem Renaissance movement[3] and the Chicago Black Renaissance in the 1940s and reinforced in the 1960s and 1970s with the influence of the Black Power, Black Arts Movement and feminism.[12][13] With artists like Lois Jones, she helped to create what critic Freida High Tesfagiorgis called an "Afrofemcentrist" analytic.[18]

The Taller de Gráfica Popular pushed her to adapt her work to reach the broadest possible audience, which generally meant balancing abstraction with figurative images. She stated of her time at the TGP, "I learned how you use your art for the service of people, struggling people, to whom only realism is meaningful."[2]

Catlett also acknowledged her artistic contributions as influencing younger black women. She relayed that being a black woman sculptor "before was unthinkable ... There were very few black women sculptors – maybe five or six – and they all have very tough circumstances to overcome. You can be black, a woman, a sculptor, a print-maker, a teacher, a mother, a grandmother, and keep a house. It takes a lot of doing, but you can do it. All you have to do is decide to do it."[5]

No other field is closed to those who are not white and male as is the visual arts. After I decided to be an artist, the first thing I had to believe was that I, a black woman, could penetrate the art scene, and that, further, I could do so without sacrificing one iota of my blackness or my femaleness or my humanity.

— Elizabeth Catlett[22]

Catlett remained an active artist until her death.[4][15] The artist died peacefully in her sleep at her studio/home in Cuernavaca on April 2, 2012, at the age of 96.[1][3]She was survived by her three sons, ten grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.[2]

Abbreviated biography courtesy of Wikipidia. Link to full bio:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Catlett

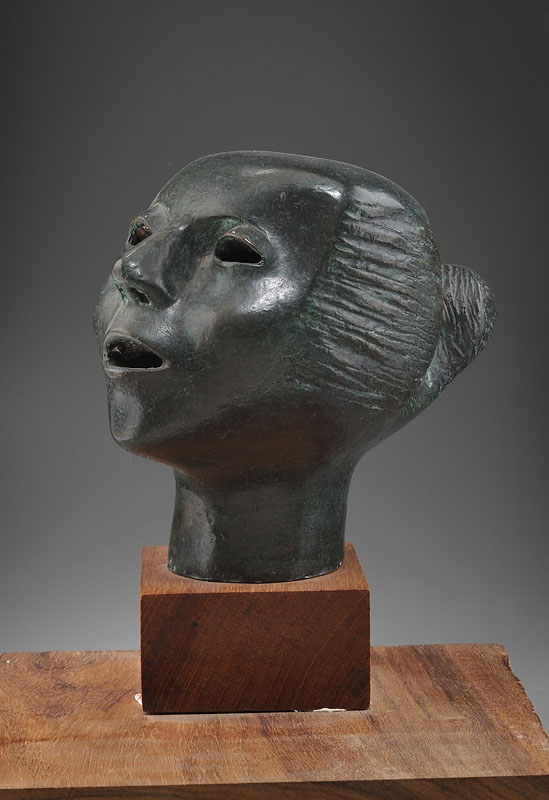

Cabeza Contando

Bronze

9 3/4 inches high

1960

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

El Baile

Color Lithograph

16x28 1/2 inches

1970

Signed and dated

Numbered 26/30

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

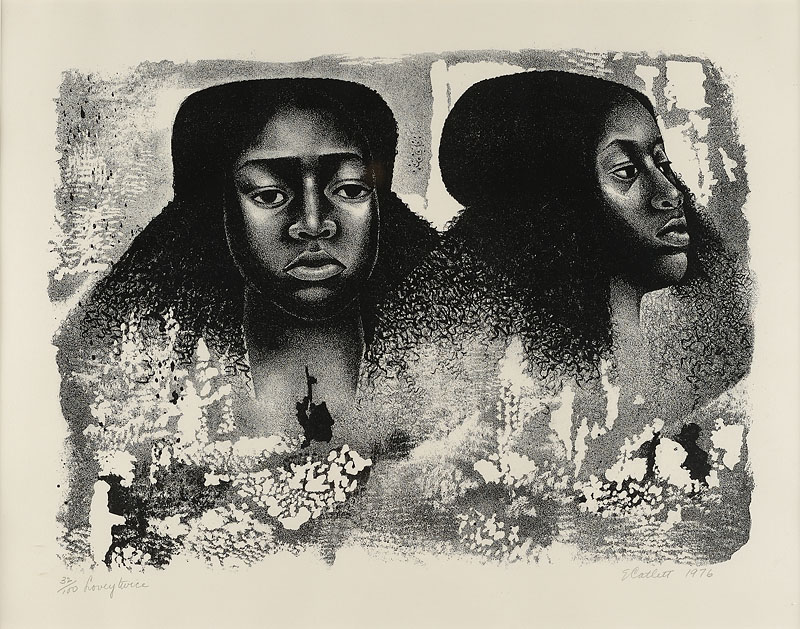

Lovey Twice

Lithograph

21x15 1/2 inches

1976

Signed and dated

Numbered 32/100

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

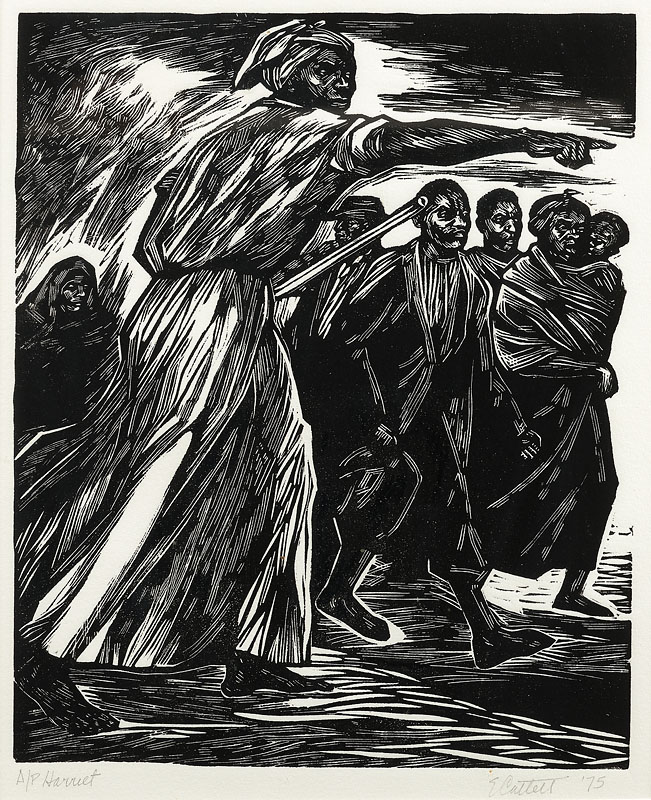

Harriet

Linocut

12 1/2x10 inches

1975

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

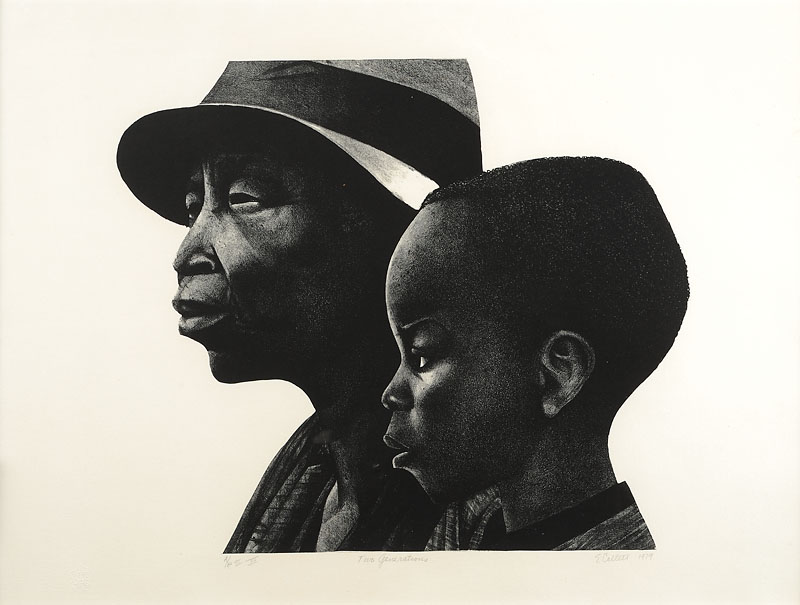

Two Generations

Lithograph

28x21 inches

1979

Signed and dated

(Annotation: Artist proof III/XX)

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio