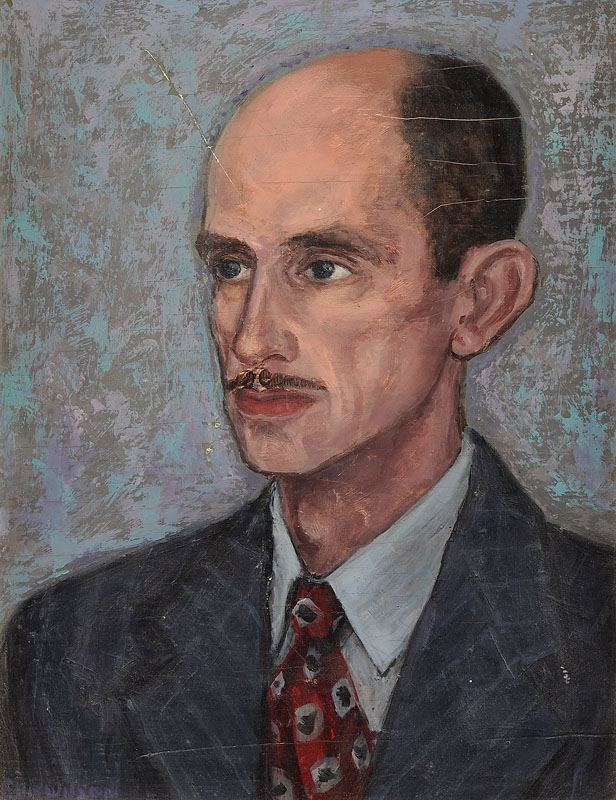

Joseph Kersey (1909-1983)

Joseph Kersey (1909-1983)

Bronzeville artist known mainly for sculpture. Joseph Kersey was a member of George Neal's Art Crafts Guild and a founding member of the South Side Community Art Center. His work was featured at the informal opening of the art center gallery. Kersey also received an Honorable Mention for his sculpture entitled “Anna” at the American Negro Exposition in 1940.

Bio courtesy of www.tylerfineart.com. Link to full bio: http://tfa-exhibits.com/new-page-1/

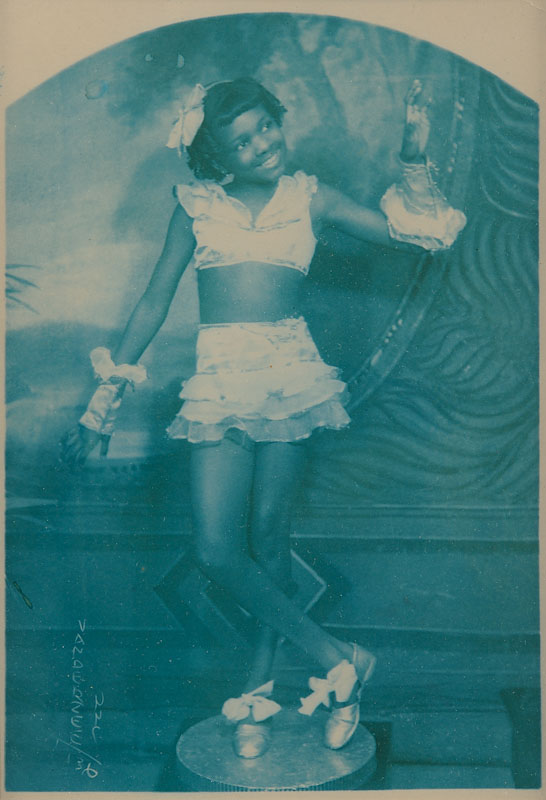

Ellen Jane

Plaster

9 3/8x7x7 inches

c. 1930

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

The Spirited Singer (Marion Anderson)

Plaster

10 3/4x7 3/4x6 3/4 inches

c. 1950

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Columbus Knox (1923-1999)

Like many artists, Columbus Knox began drawing early in childhood. "Even at an early age, art was a source of enjoyment to me and I was fortunate because my brother drew and I could look over his shoulder and watch him draw and make illustrations, which influenced me extensively."

Knox was born in Philadelphia, where he attended a number of schools, and where he received support and encouragement from his teachers. After graduation from high school, he was awarded a four-year scholarship to the Museum School of Industrial Arts in Philadelphia. Later, Knox completed a tour of duty during World War II in which he participated in five campaigns, including landing on Omaha Beach. After his discharge from the Army, Knox returned to the Museum School of Industrial Arts in Philadelphia and resumed his studies. After his graduation, he began a career as a professional artist, teaching and painting commissioned works, as well as painting his own art work. One of his works, Charging Warriors, is listed in Who’s Who in Black Art.

Bio courtesy of www.givmg.com. Link to full bio: http://www.qivmg.com/gibbes/html/knox/knoxf.htm

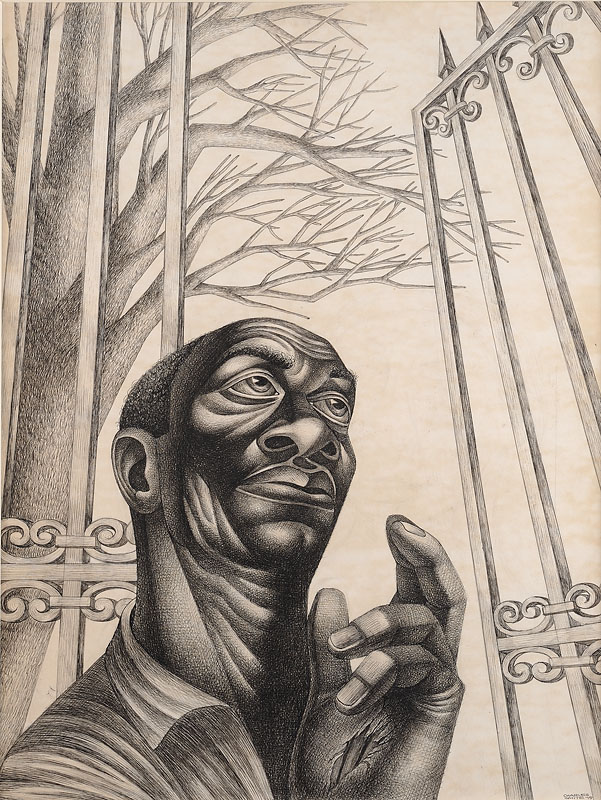

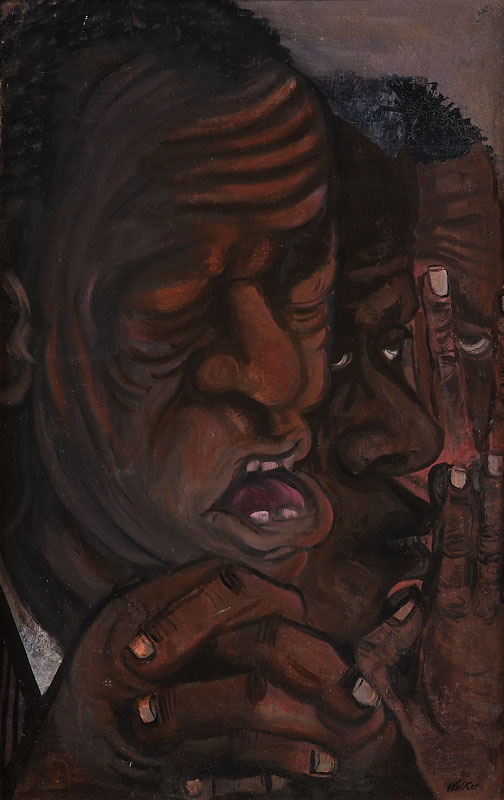

Praying Worker

Acrylic on canvas

24x36 inches

c. 1990

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Richard Mayhew (b. 1924)

Richard Mayhew was born in Massapequa, New York to Native American and African American parents. Considered one of Americaºs greatest living landscape painters, Mayhew has had over thirty solo exhibitions.

His work is in the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum, The Whitney Museum of American Art and The Brooklyn Museum in New York; The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois; The Smithsonian and The National Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C. among numerous others.

Throughout his career his work has been described as Abstract, Impressionist, Realist and Romantic. He has uniquely synthesized his experiences, his heritage and the influences of his various teachers, Rubin Tam, Edwin Dickinson, Max Beckmann and Hans Hofmann. The power of Mayhew's paintings derives from his intimacy and absorption with nature.

After his first one-person exhibition in 1957, Mayhew received a grant to study in Europe. Upon his return, in 1963, Mayhew along with other artists and writers founded "Spiral," a contingent of black intellectuals who were united in their dedication for civil rights in the art world. As one of the few living members of this historic group, Mayhew has achieved what the group set out to accomplish.

His work, acclaimed for the depth of beauty and serenity, has universal appeal. His large scale oils and his small, intimate watercolors, create moody, atmospheric landscapes which evoke the work of George Inness and Henry Tanner.

"Mayhew represents a bridge between the older black artists who developed through the WPA in the 1930s and those who, after World War II, attended art schools and matured during the turbulent civil rights movement of the 1960s and the rise of Abstract Expressionism." -Romare Bearden

Bio courtesy of www.blouinartinfo.com. Link to full bio:

http://www.blouinartinfo.com/artists/richard-mayhew-3530

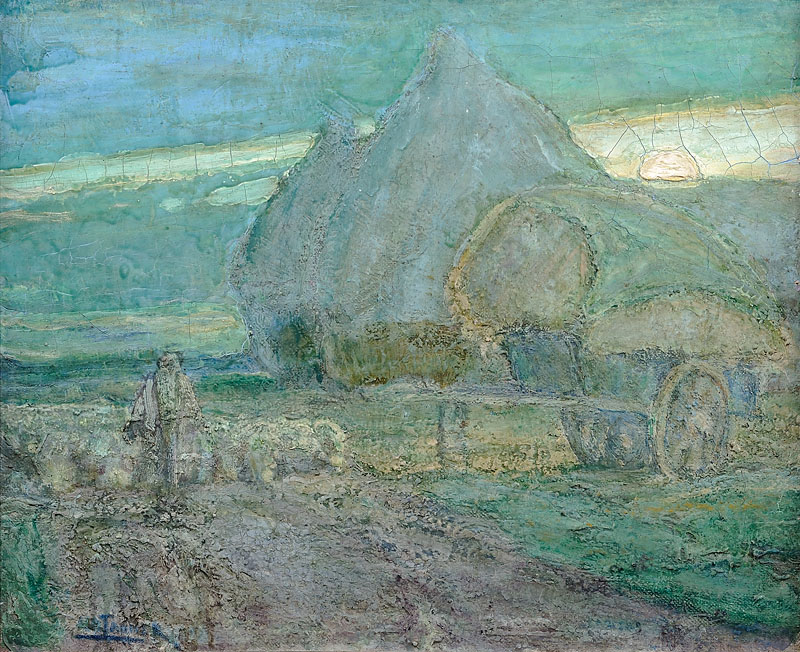

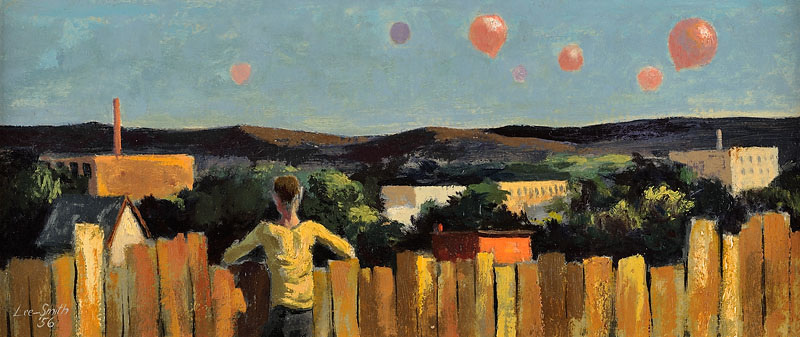

West Wind

Oil on canvas

54x74 inches

1954

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Yvonne Cole Meo (b. 1929)

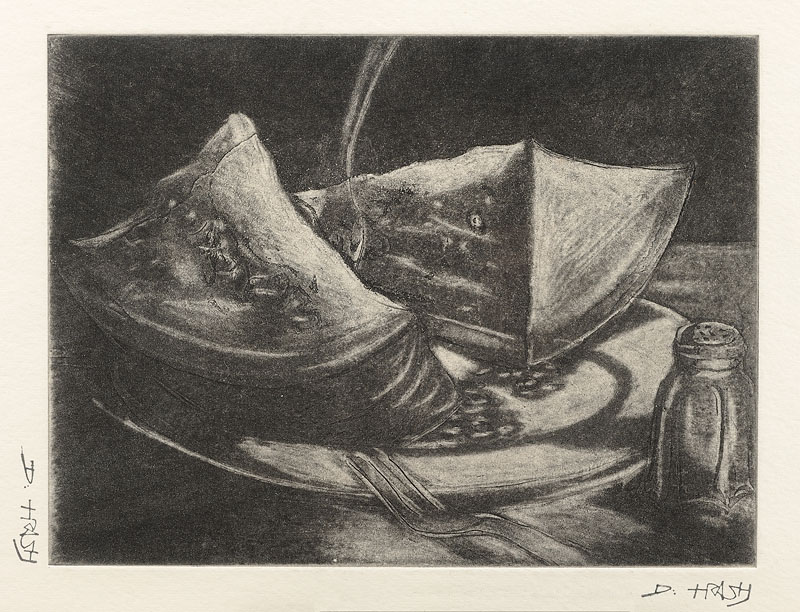

Cotton Pickers

Lithograph

10 3/4x 7 3/4 inches

c. 1950

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Gus Nall (1919-1995)

Gus Nall (1919 – 1995) was an African American painter during the mid-20th century in Chicago, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan. Born in Illinois, Nall’s most known work is his painting "Lincoln Speaks to Freedmen on the Steps of the Capital at Richmond" (1963),[1][2][3] which was commissioned by the state of Illinois in honor of the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.[4][5]

He studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and as well as in Paris. During his life, he was featured in Art Gallery Magazine (1968, "The Afro-American Issue”)[6] as well as Carol Myers' Black Power in the Arts.[3]

Nall’s work consisted of elongated human figures influenced by Cubist and Expressionist styles of painting, and African art.[7] His art most often portrays representations of African Americans. He was influenced by Archibald Motley and Eldzier Cortor, who were fellow artists from Chicago. Nall’s work allowed him to become a role model to fellow painters as well as those interested in his life as an artist. Nall had an inspiring effect on the life of fellow artist and writer Clarence Majorwho looked up to him.[7] His painting "Lincoln Speaks to Freedmen on the Steps of the Capital at Richmond" (1963) is on permanent exhibit in the DuSable Museum of African American History.[4]

Bio courtesy of Wikipedia. Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gus_Nall

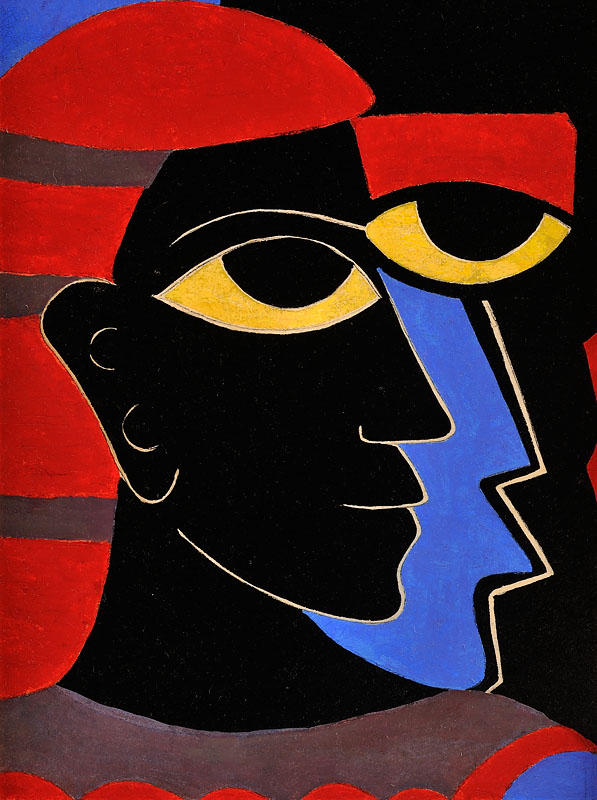

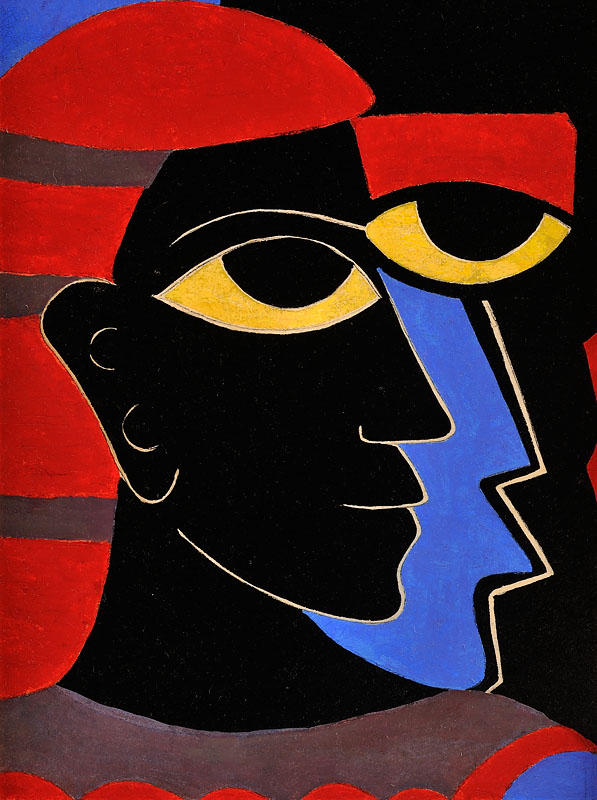

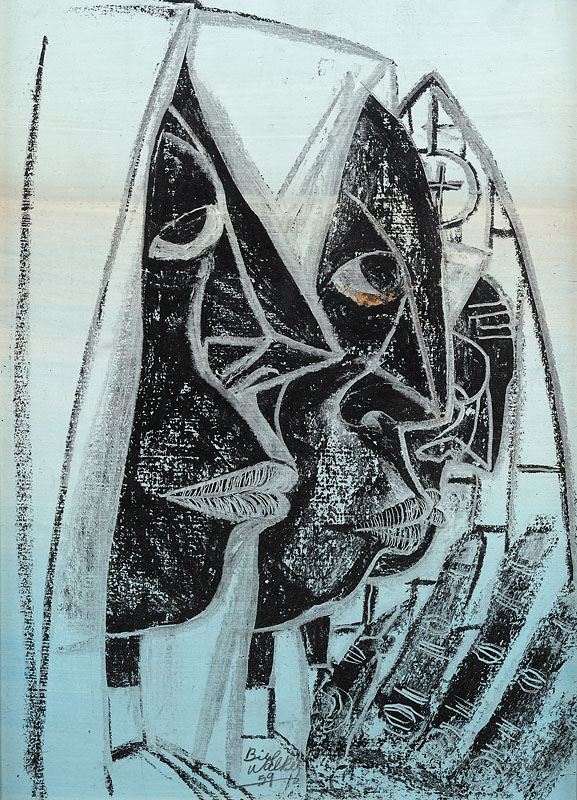

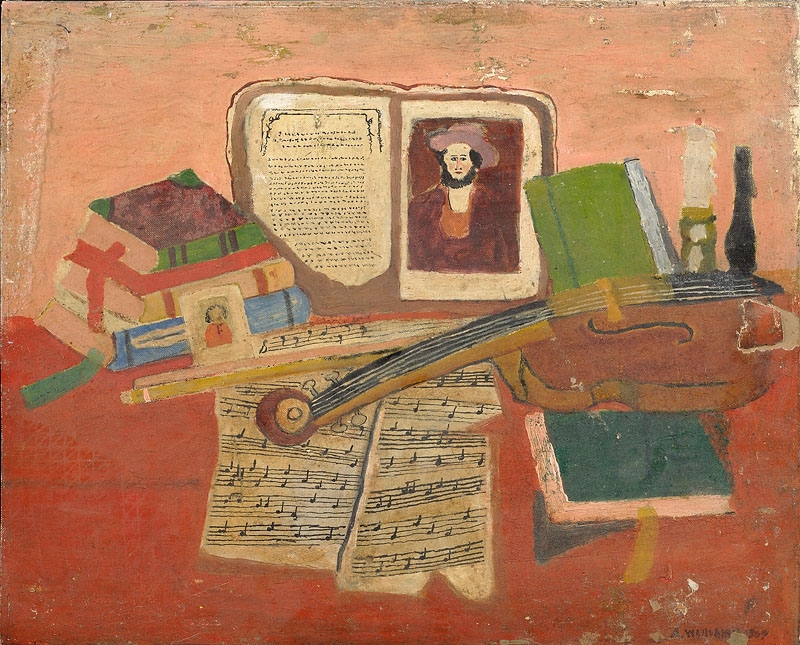

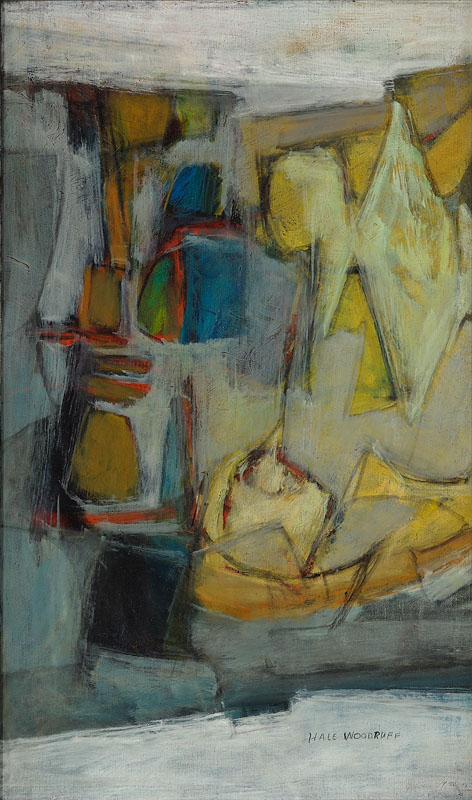

Abstract

Oil on board

55 1/2x30 inches

c. 1960

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

H Narbutt (1899-1989)

Couple Dancing

Oil on canvas

24x18 inches

c. 1940

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

George Neal (1906-1938)

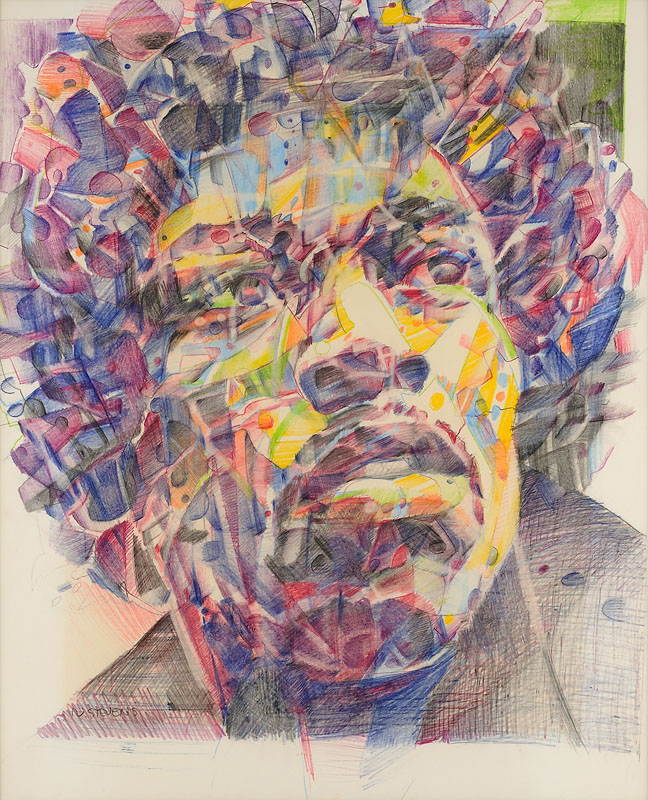

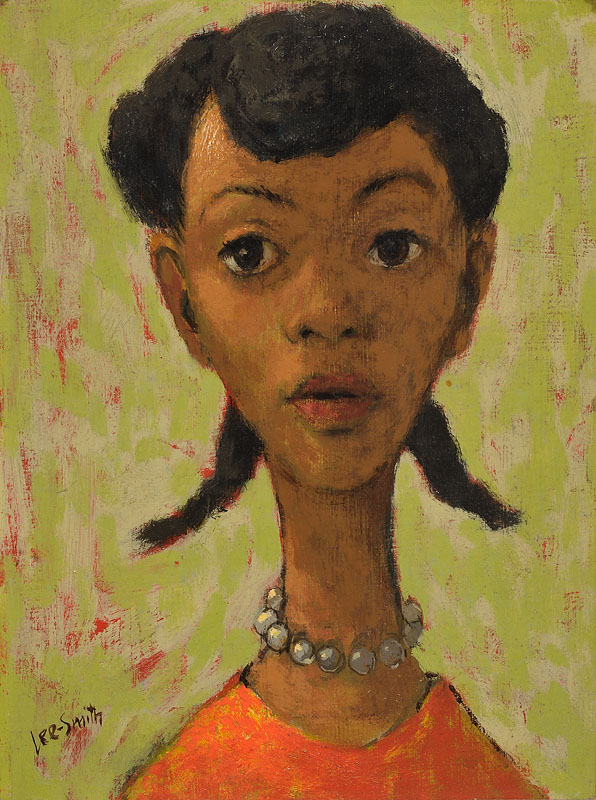

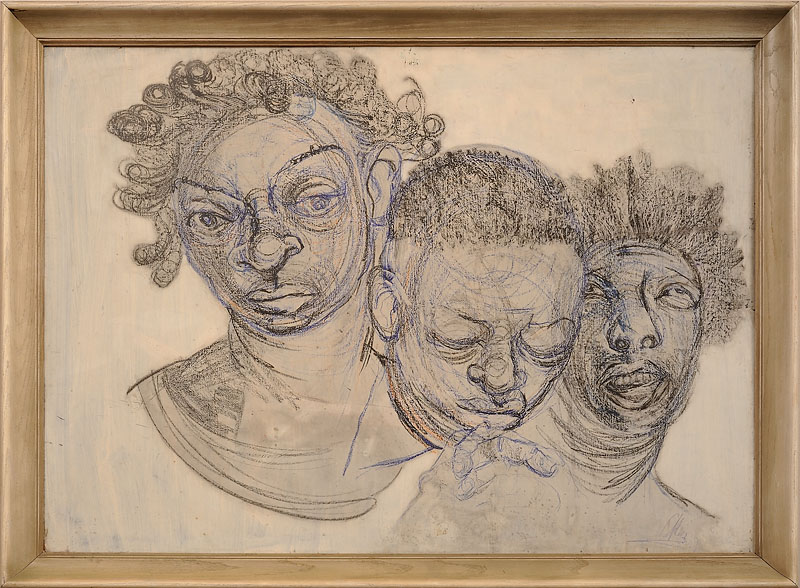

Portrait of a Girl

Mixed media on paper

9x7 1/2 inches

1936

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Hayward Oubre (1916-2006)

Born to a family of African and French descent, Oubre’s youthful artistic talent was encouraged in the New Orleans parochial schools he attended. Following high school, he enrolled at Dillard University, where he was a standout member of the football and track teams, an illustrator for the college newspaper, and the institution’s first art major. Upon his graduation in 1939, Oubre continued his studies at Atlanta University, thriving under the tutelage of painter and muralist Hale Woodruff and sculptor Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, who encouraged Oubre to submit his work to the annual Atlanta University exhibitions. In 1941, Oubre was assigned to help with a special art initiative at Tuskegee Institute, where he met George Washington Carver, an admirer of the fledgling artist’s work. Oubre temporarily relinquished his artistic pursuits later that year when he was drafted into military service. Serving with the Army Corps of Engineers during World War II, Oubre joined 3,700 African American soldiers charged with building a 1500-mile military supply route—now known as the Alcan Highway—that connected Alaska to the continental United States. These soldiers labored under brutal conditions to complete the assignment in eight months. Thanks to the GI Bill, Oubre was able to continue his education in art at the University of Iowa, earning his master’s degree from the University of Iowa. He then launched a career as an art educator, teaching first at Florida A&M University, then at Alabama State College, and, later, at Winston-Salem State University, where he initiated a studio art program.

Deeply attached to his Southern heritage, Oubre relied on childhood memories as he composed paintings of African American life in New Orleans. His simplified, sometimes abstracted, forms reflect the artist’s familiarity with Picasso’s Analytic and Synthetic Cubism. Though he had been working with clay and wood to create closed-form sculptures, it was during his tenure at Alabama State College in the 1950s that Oubre began creating his acclaimed wire sculptures. Slowly and delicately shaping wire clothes hangers with pliers, the artist confronted structural challenges that demanded a considerable amount of strength and, at times, physical pain, to overcome. Nicknamed by his students as the “master of torque,” Oubre described his method in detail in his 1960 publication, The Art of Wire Sculpture. One reviewer writing of Oubre’s sculptures opined that “light and air are as critical to the work as the metal that gives them definition.”

During his thirty-year career as an educator, Oubre mentored countless aspiring African American artists, including Floyd Coleman who would later become the chair of Howard University’s art department. In an effort to provide his painting students with the proper learning material, Oubre developed and copyrighted “a concise study of color mixing and color relationships” a color wheel that updated and expanded the 1810 color triangle developed by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Though Oubre’s work was not widely exhibited during his lifetime, his oeuvre has attracted increased curatorial attention and examples of his work are represented in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mint Museum of Art, and University of Delaware. In 1993, the Pentagon honored Oubre and other surviving soldiers from the Alcan Highway battalion for their service.

Bio courtesy of www.thejohnsoncollection.org

Link to full bio: http://thejohnsoncollection.org/hayward-oubre/

Pensive Family

Oil on canvas

38x23 1/2 inches

1949

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

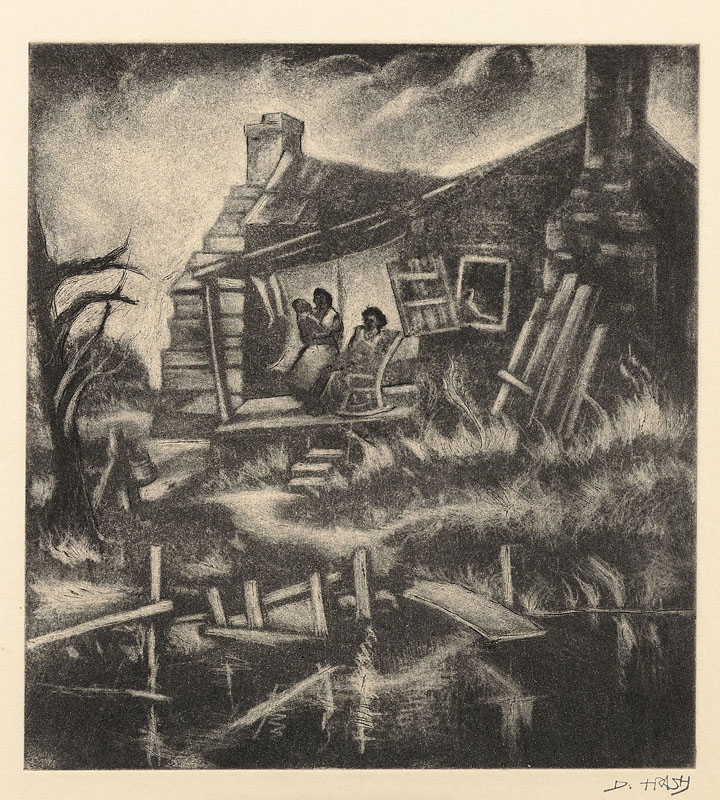

Slave Cabin in the Woods

Oil on canvas

13 1/4X17 1/4 inches

Year unknown

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

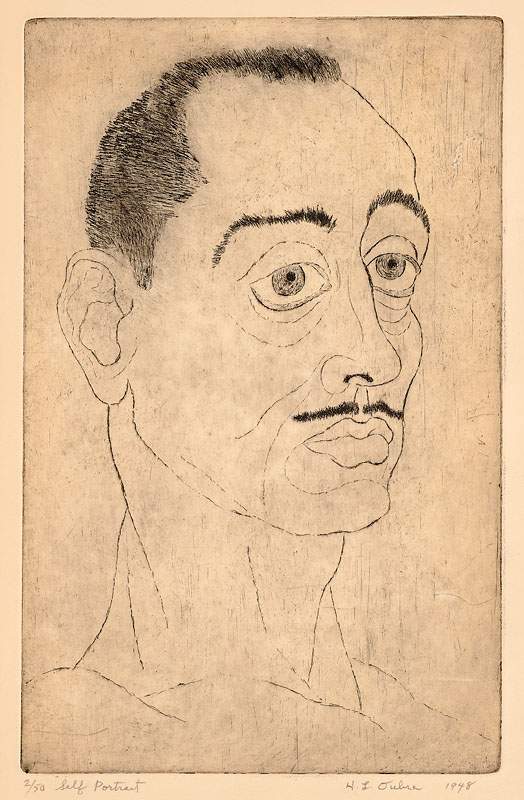

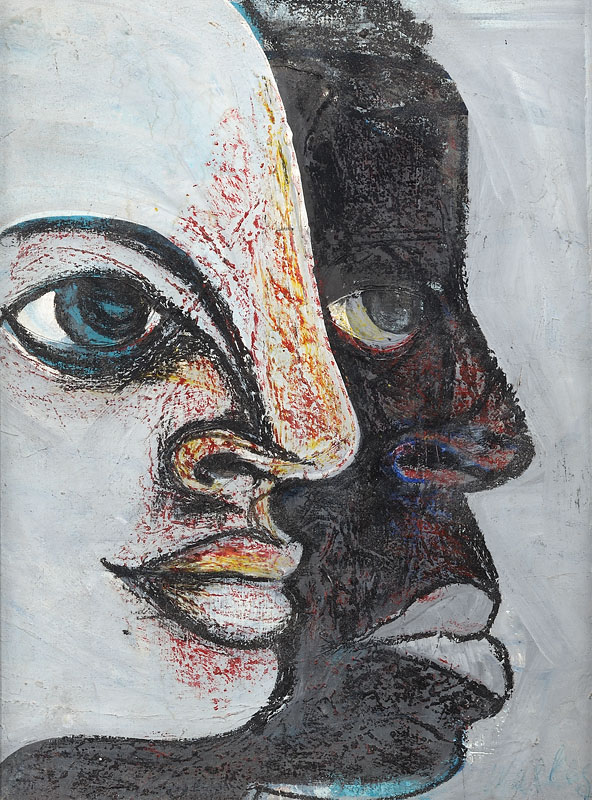

Self Portrait

Etching

16x10 1/4 inches

1948

Signed and dated

Edition 2/50

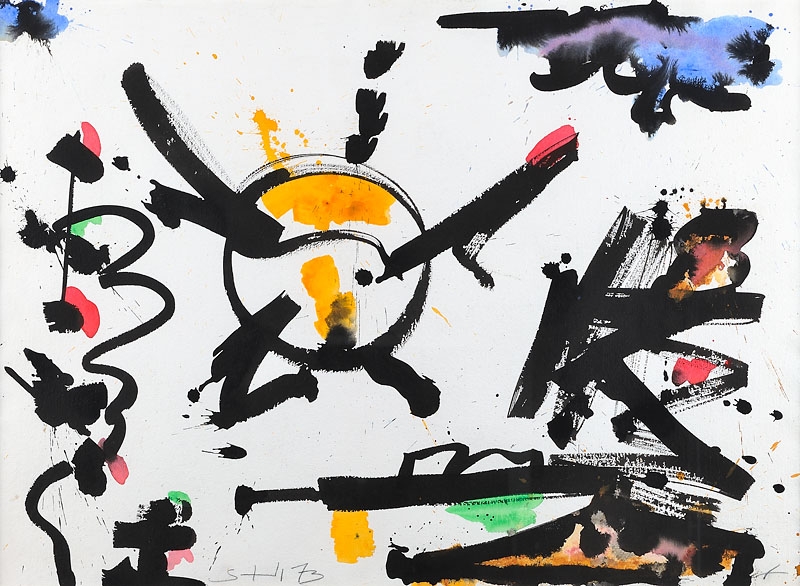

Joe Overstreet (b.1 933)

Joe Overstreet was born in Conehatta, Mississippi, in 1933. His family relocated five times before settling in Berkeley, California, in 1946. After graduating from Oakland Technical High School in 1951, he joined the Merchant Marines and traveled the world, off and on, until 1958. He also studied art at Contra Costa College and the California School of Fine Arts in the early 1950s. While living in San Francisco he was mentored by Sargent Johnson, who was a passionate supporter of black artists and a major intellectual influence on Overstreet. He gave his first solo exhibitions in San Francisco, at venues such as the Vesuvio Cafe, and took part in the North Beach area Beat scene.[1]

From 1955 to 1957, he worked as an animator at Walt Disney Studios in Los Angeles. Frustrated by the repetitive nature of the work, and increasingly drawn to New York painting, he moved to New York City with his friend, the poet Bob Kaufman, and worked for a time designing window displays for department stores.[2]

It was in the Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village, Overstreet recalled later, that he received his "real art education and development". At the time it was a hangout for Abstract Expressionist painters and Beat writers, and Overstreet had many edifying discussions there with artists such as Hale Woodruff, Romare Bearden, and Willem de Kooning. Woodruff encouraged him to incorporate African elements in his work. Overstreet lived for a time in a loft above jazz musician Eric Dolphy, before moving to an artists' community in the Bowery, where he remained for 15 years.[1]

African-American abstract artists have often been overlooked by critics and historians, especially within the Abstract Expressionist movement.[3][4] Perhaps for this reason, Overstreet first gained recognition for his socially-themed works of the 1960s rather than as an abstract expressionist.[5]

In the mid-1960s, Overstreet became active in the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Arts Movement. He organized exhibitions and projects for black artists, and worked with Amiri Baraka as Art Director of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre and School (BARTS) in Harlem. It was during this period that he created one of his best known (and least abstract) paintings: The New Jemima, which subverts the stereotypical black image of Aunt Jemima. Unlike the original character, a domestic servant who exists to please others, Overstreet's Jemima gleefully wields a machine gun. Another social protest piece, Strange Fruit, was inspired by the eponymous anti-lynching song made famous by Billie Holiday. Birmingham Bombing was a response to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in which four schoolgirls were killed.[6]

Years later, when asked if he saw any conflict between his belief in the universality of art and his socially-themed paintings of the 1960s, Overstreet responded, "...I think when you look at Catholic Christian art, that's universal, isn't it? When you look at Michelangelo, sixteenth-century art, is that not universal? Isn't that social?...I don't think Aunt Jemima with a machine gun is any less universal than what I'm doing now."[6]

During this period, Overstreet took part in many group and solo exhibitions in New York and California. He began working with shaped canvases, which eventually led to other innovations. In the early 1970s he created a "nomadic art" series using loose canvases suspended in air by ropes and dowels; the effect is reminiscent of the tents and tepees of nomadic people and the sails of slave ships.[7] From 1970 to 1973 he taught studio courses at the University of California at Hayward.[1]

In 1974, with Corinne Jennings and Samuel C. Floyd, Overstreet co-founded Kenkeleba House, an East Village gallery and artist center, to promote minority artists. According to Jennings, black artists were so chronically underrepresented in mainstream galleries at the time that starting a new gallery was preferable to "fighting the Whitney". The neighborhood was then a low-rent area plagued by drug-related crime; in recent years, it has become gentrified. Kenkeleba House is named for a West African plant (Combretum micranthum) prized for its medicinal properties. The gallery displays mostly large works and large group exhibits and includes an outdoor sculpture garden.[8] It also hosts educational programs such as artist lectures and performances. Overstreet still keeps his studio at Kenkeleba House and serves as Artistic Director.[6]

As a young artist in the 1990s, Odili Donald Odita worked at Kenkeleba House, where he was astonished to discover the work of so many older, and relatively unknown, African-American abstract artists. He later said he felt indebted to them for their persistence in the face of an unappreciative art market. Odita began interviewing abstract painters from the 1970s and 80s, such as Howardena Pindell, Alvin D. Loving, Edward Clark, Frank Bowling, and Stanley Whitney, and has since begun lecturing about them at universities.[3]

In the 1980s, Overstreet worked on a commission to produce a series of 75 steel and neon panels for the San Francisco International Airport.[1] He also created his semi-figurative Storyville series, which recalls the New Orleans jazz scene of the early '40s.[6] While exhibiting at the Dakar Biennale in Senegal in 1992, he visited the House of Slaves at Gorée, an experience that led him to produce his Door of No Return series. Over the next two years he explored the possibilities of paint texture in large, stretched canvas paintings that reflect his interest in sacred geometry. In his Silver Screens and Meridian Fields of the early 2000s, his interest in transparency led him to paint on steel wire cloth.[1]

Overstreet's work has been included in solo and group exhibitions at museums and festivals around the world, including the Tate Modern in London, the Dakar Biennalein Senegal, and the Tokushima Modern Art Museum in Japan, and is included in the permanent collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the Everson Museum, the Oakland Museum,[9] the Menil Collection, and many others.[7]

Bio courtesy of www.wikipedia.com. Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joe_Overstreet

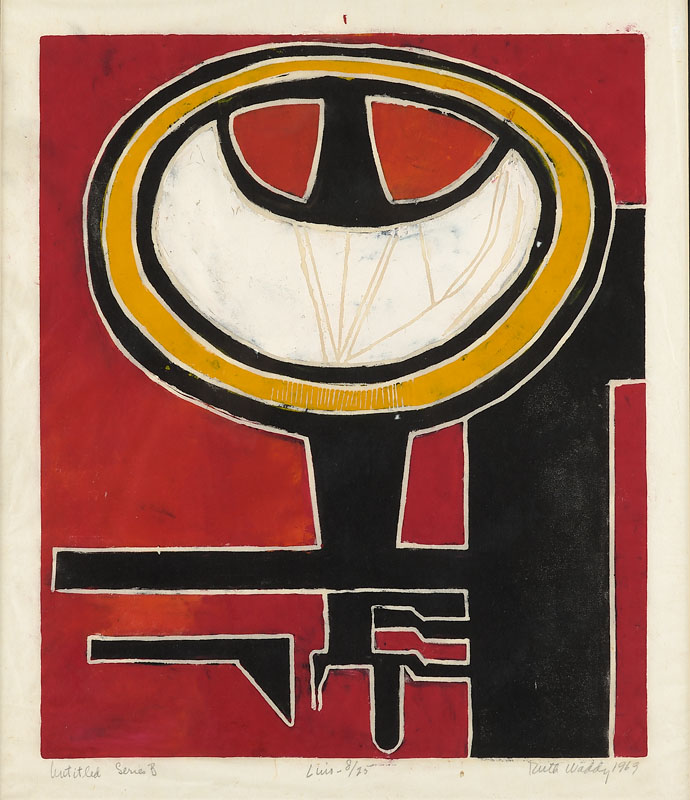

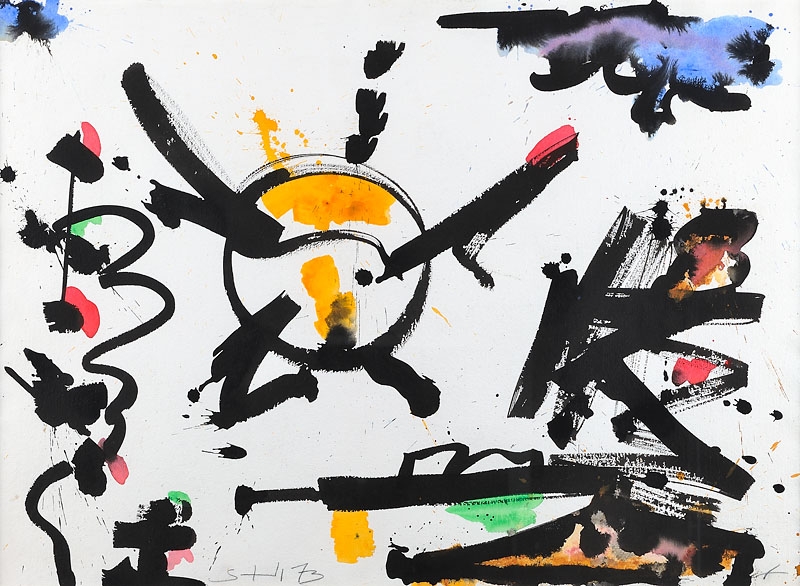

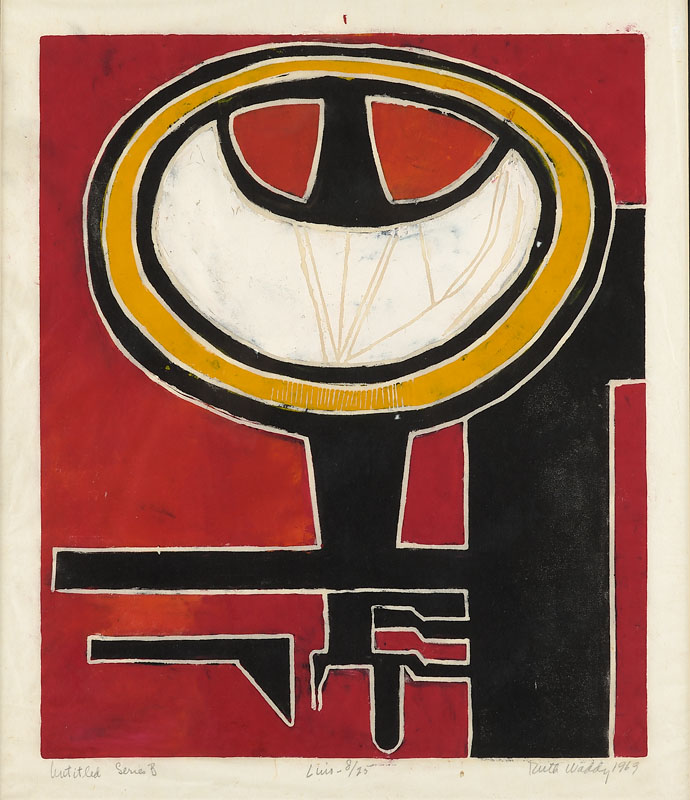

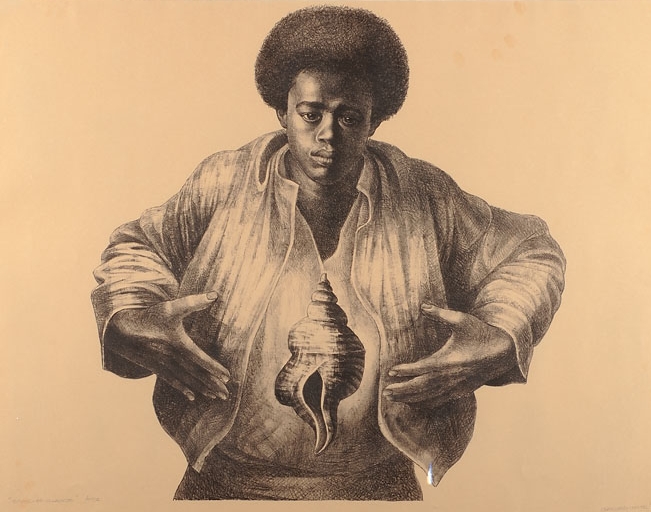

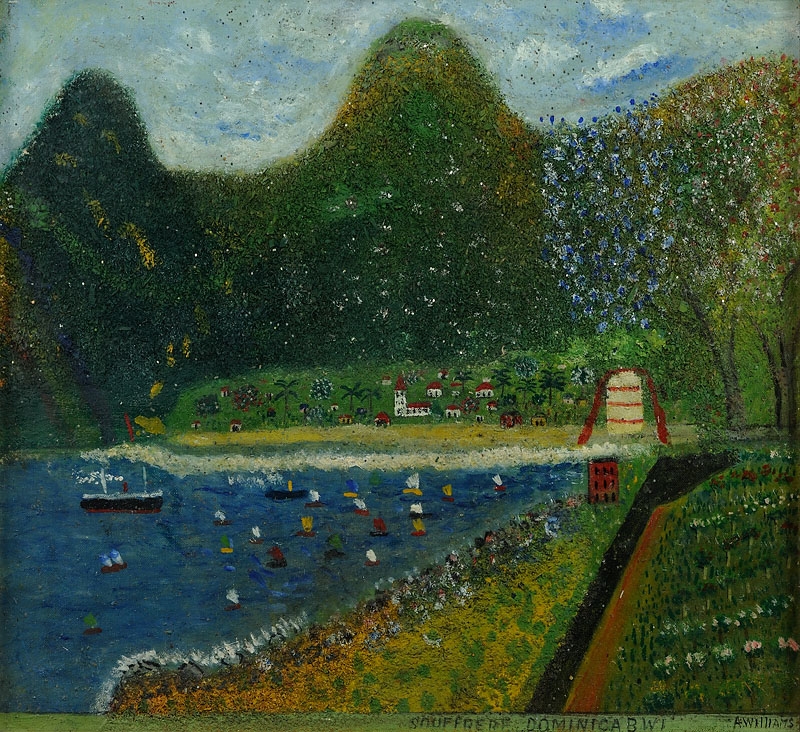

Untitled

Mixed media on paper

25x18 inches

1969

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

William Pajaud (1925-2015)

William Etienne "Bill" Pajaud (August 3, 1925 – June 16, 2015) was an African-American artist known for his paintings exploring themes of jazz.[1] He was born in New Orleans, Louisiana. Pajaud's work has been featured in exhibitions at California African American Museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Las Vegas Museum of Art. His work is in the collections of the Pushkin Museum, the Amistad Research Center, and the National Museum of American Art.[2] He has been a member of the Society of Graphic Designers, the Los Angeles County Art Association, and the National Watercolor Society, of which he served as president from 1974 to 1975. His honors include the 1969 PRSA Art Exhibition Award of Merit, the 1971 National Association of Media Women Communications Award, the 1975 University of the Pacific Honor, the 1978 Paul Robeson Special Award for Contribution to the Arts, the 1981 PR News Gold Key Award, the 1981 League of Allied Arts Corporation Artists of Achievement Award, and the 2004 Samella Award.[3] He died in Los Angeles on June 16, 2015 at the age of 89.[4]

Bio courtesy of www.wikipedia.com. Link to bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Pajaud

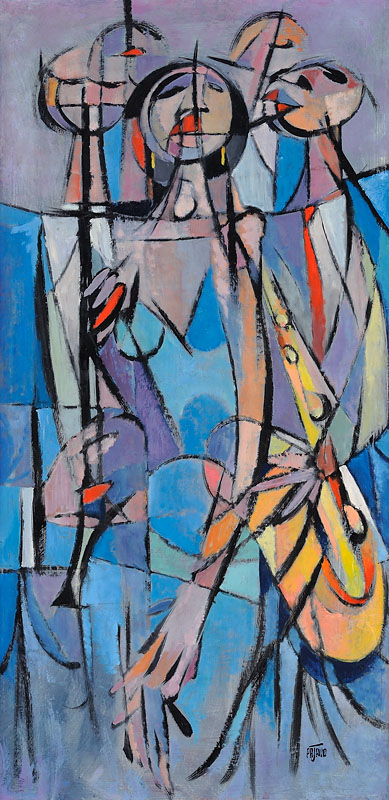

Jazz Ensemble

Tempura on board

43x21 inches

1950

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Gordon Parks (1912-2006)

Gordon Roger Alexander Buchanan Parks (November 30, 1912 – March 7, 2006) was an American photographer, musician, writer and film director, who became prominent in U.S. documentary photojournalism in the 1940s through 1970s—particularly in issues of civil rights, poverty and African-Americans—and in glamour photography.

As the first famous pioneer among black filmmakers, he was the first African American to produce and direct major motion pictures—developing films relating the experience of slaves and struggling black Americans, and creating the "blaxploitation" genre. He is best remembered for his iconic photos of poor Americans during the 1940s (taken for a federal government project), for his photographic essays for Life magazine, and as the director of the 1971 film Shaft. Parks also was an author, poet and composer.[2][3][4][5]

Parks was born in Fort Scott, Kansas, the son of Sarah (née Ross) and Jackson Parks, on Nov. 30, 1912.[3][4][6][7][8] He was the youngest of fifteen children. His father was a farmer who grew corn, beets, turnips, potatoes, collard greens, and tomatoes. They also had a few ducks, chickens, and hogs.[9]

He attended a segregated elementary school. The town was too small to afford a separate high school that would facilitate segregation of the secondary school, but blacks were not allowed to play sports or attend school social activities,[10] and they were discouraged from developing any aspirations for higher education. Parks related in a documentary on his life that his teacher told him that his desire to go to college would be a waste of money.

When Parks was eleven years old, three white boys threw him into the Marmaton River, knowing he couldn't swim. He had the presence of mind to duck underwater so they wouldn't see him make it to land.[11] His mother died when he was fourteen. He spent his last night at the family home sleeping beside his mother's coffin, seeking not only solace, but a way to face his own fear of death.[12]

Soon after, he was sent to St. Paul, Minnesota, to live with a sister and her husband. He and his uncle argued frequently and Parks was finally turned out onto the street to fend for himself at age 15. Struggling to survive, he worked in brothels, and as a singer, piano player, bus boy, traveling waiter, and semi-pro basketball player.[3][6] In 1929, he briefly worked in a gentlemen's club, the Minnesota Club. There he not only observed the trappings of success, but was able to read many books from the club library.[13] When the Wall Street Crash of 1929 brought an end to the club, he jumped a train to Chicago,[14] where he managed to land a job in a flophouse.[15]

While working as a waiter in a railroad dining car, he began seeing the portfolios of photographers in picture magazines, and decided to become a photographer.[6]

At the age of 25, Parks was struck by photographs of migrant workers in a magazine. He bought his first camera, a Voigtländer Brillant, for $7.50 at a Seattle, Washington, pawnshop[16] and taught himself how to take photos. The photography clerks who developed Parks' first roll of film applauded his work and prompted him to seek a fashion assignment at a women's clothing store in St. Paul, Minnesota, owned by Frank Murphy. Those photographs caught the eye of Marva Louis, wife of heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis. She encouraged Parks to move to Chicago in 1940,[17] where he began a portrait business and specialized in photographs of society women. Parks's photographic work in Chicago, especially in capturing the myriad experiences of African Americans across the city, led him to receive the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, which, in turn, contributed to being asked to join the Farm Security Administration under the auspice of Roy Striker[6][18]

Over the next few years, Parks moved from job to job, developing a freelance portrait and fashion photographer sideline. He began to chronicle the city's South Sideblack ghetto and, in 1941, an exhibition of those photographs won Parks a photography fellowship with the Farm Security Administration (FSA).[6]

Working at the FSA as a trainee under Roy Stryker,[4][6] Parks created one of his best-known photographs, American Gothic, Washington, D.C.,[19] named after the iconic Grant Wood painting, American Gothic—a legendary painting of a traditional, stoic, white American farm couple—which bore a striking, but ironic, resemblance to Parks' photograph of a black menial laborer. Parks' "haunting" photograph shows a black woman, Ella Watson, who worked on the cleaning crew of the FSA building, standing stiffly in front of an American flag hanging on the wall, a broom in one hand and a mop in the background. Parks had been inspired to create the image after encountering racism repeatedly in restaurants and shops in the segregated capital city.[20]

Upon viewing the photograph, Stryker said that it was an indictment of America, and that it could get all of his photographers fired.[21] He urged Parks to keep working with Watson, however, which led to a series of photographs of her daily life. Parks said later that his first image was overdone and not subtle; other commentators have argued that it drew strength from its polemical nature and its duality of victim and survivor, and so has affected far more people than his subsequent pictures of Mrs. Watson.[22]

(Parks' overall body of work for the federal government—using his camera "as a weapon"—would draw far more attention from contemporaries and historians than that of all other black photographers in federal service at the time. Today, most historians reviewing federally commissioned black photographers of that era focus almost exclusively on Parks.)[20]

After the FSA disbanded, Parks remained in Washington, D.C. as a correspondent with the Office of War Information,[6][7]where he photographed the all-black 332d Fighter Group.[23] He was unable to follow the group in the overseas war theatre, so he resigned from the O.W.I.[24] He would later follow Stryker to the Standard Oil Photography Project in New Jersey, which assigned photographers to take pictures of small towns and industrial centers. The most striking work by Parks during that period included, Dinner Time at Mr. Hercules Brown's Home, Somerville, Maine (1944); Grease Plant Worker, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (1946); Car Loaded with Furniture on Highway (1945); and Ferry Commuters, Staten Island, N.Y. (1946).

Parks renewed his search for photography jobs in the fashion world. Following his resignation from the Office of War Information, Parks moved to Harlem and became a freelance fashion photographer for Vogue under the editorship of Alexander Liberman.[25] Despite racist attitudes of the day, Vogue editor, Liberman, hired him to shoot a collection of evening gowns. Parks photographed fashion for Vogue for the next few years and he developed the distinctive style of photographing his models in motion rather than poised. During this time, he published his first two books, Flash Photography (1947) and Camera Portraits: Techniques and Principles of Documentary Portraiture (1948).

A 1948 photographic essay on a young Harlem gang leader won Parks a staff job as a photographer and writer with America's leading photo-magazine, Life. His involvement with Life would last until 1972.[4] For over 20 years, Parks produced photographs on subjects including fashion, sports, Broadway, poverty, and racial segregation, as well as portraits of Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Muhammad Ali, and Barbra Streisand. He became "one of the most provocative and celebrated photojournalists in the United States."[26]

His photographs for Life magazine, namely his 1956 photo essay, titled "The Restraints: Open and Hidden,"[27] illuminated the effects of racial segregation while simultaneously following the everyday lives and activities of three families in and near Mobile, Alabama: the Thronton’s, Causey’s, and Tanner’s. As curators at the High Museum of Art Atlanta note, while Parks’ photo essay served as decisive documentation of the Jim Crow South and all of its effects, he did not simply focus on demonstrations, boycotts, and brutality that were associated with that period instead, however, he "emphasized the prosaic details" of the lives of several families.[28][29]

An exhibition of photographs from a 1950 project Parks completed for Life was exhibited in 2015 at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.[30] Parks returned to his hometown, Fort Scott, Kansas, where segregation persisted, and he documented conditions in the community and the contemporary lives of many of his eleven classmates from the segregated middle school they attended. The project included his commentary, but the work was never published by Life.

During his years with Life, Parks also wrote a few books on the subject of photography (particularly documentary photography), and in 1960 was named Photographer of the Year by the American Society of Magazine Photographers.[4]

Parks had four children: Gordon, Jr., David, Leslie, and Toni (Parks-Parsons). His oldest son Gordon Parks, Jr., whose talents resembled his father's, was killed in a plane crash in 1979 in Kenya, where he had gone to direct a film.[43][44] Parks has five grandchildren: Alain, Gordon III, Sarah, Campbell, and Satchel. Malcolm Xhonored Parks when he asked him to be the godfather of his daughter, Qubilah Shabazz.

He died of cancer at the age of 93 while living in Manhattan, New York City, and is buried in his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas.

Bio courtesy of www.wikipedia.com. Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gordon_Parks

Muslim Women in Chicago

Photograph, silver gelatin print

20x29 inches

1970

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

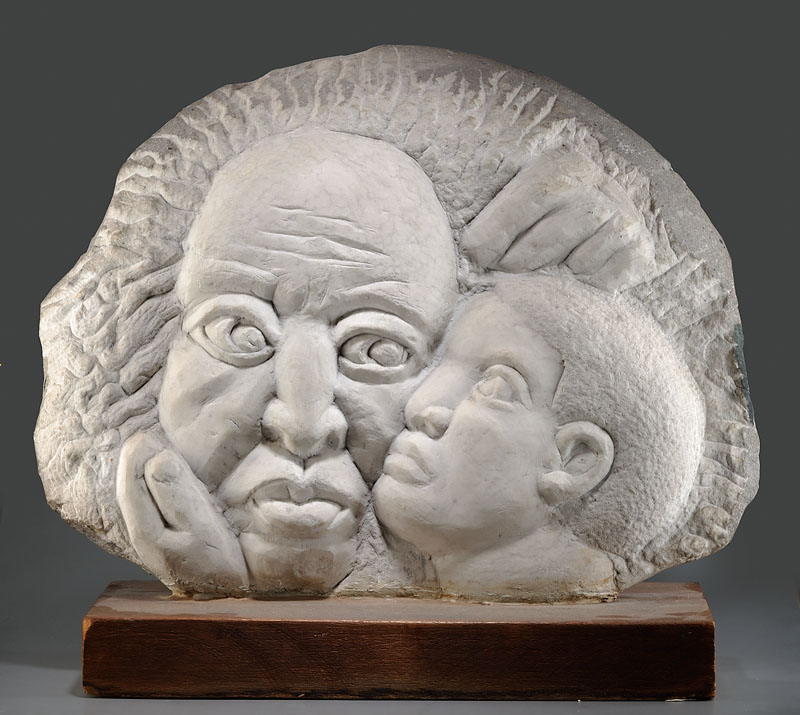

Marion Perkins (1908-1961)

Marion Perkins was one of Chicago’s foremost Renaissance sculptors and was known for his compact and expressive carved stone heads and figures. Using stone from derelict city buildings, Perkins transformed his rough found materials into realist forms. He skillfully carved them in a manner and style similar to European modernist sculptors that he believed befit the African American themes he chose to represent. Figure Sitting (c. 1939, stone), with its evenly polished surface and compressed form, is an early work predating a more mature style the artist developed in the 1940s and '50s. While a juxtaposition of textures is more evident in later works, Figure Sitting is no less emotive with the figure’s striking expression and pensive posture.

Courtesy of www.scadmoa.org

http://www.scadmoa.org/Marion_Perkins

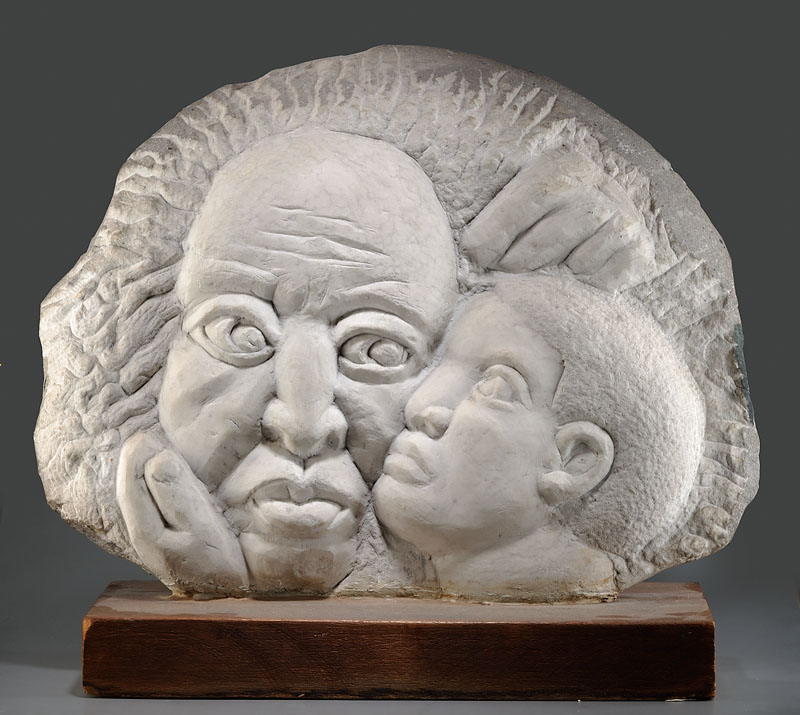

Mother and Child

Stone

15x19 inches

c. 1940

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

James Phillips (b.1945)

James Phillips’ art has been linked to his association and consequent membership with the organizations Weusi and AfriCobra. However, his accomplishments are highlighted rather than mirrored by the association of these two groups that led the Black Arts Movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s. African spirituality was the ignition, which these artists used as the connective link to the past, and African spiritual heritage was, a strong motivation for producing the art.

Through the influence of Ademola Olugebefola and other contemporary African artists and 20th Century African American artists Phillips developed his own personal style of painting. He incorporated African patterns and designs throughout his compositions which included foreground and background to portray one design. In 1973 he became a member of AfriCobra, because some of the members were starting to use similar patterns and motifs to his. That evolved into what young writers and art historians are calling the AfriCobra style or tradition.

What sets James Phillips apart is his inherent sense of aesthetics, and how noted art historian Dr. Rosalind Jeffries describes Phillips as a “master of pure color”.

James Phillips has exhibited both nationally and internationally. From coast to coast and points in between as well as the United Kingdom, Japan, Africa, St. Croix, Brazil, St. Martinique, Germany, Haiti, and Italy. Phillips' work is received with both awe and admiration, for each painting is a veritable kaleidoscope of color.

To his credit, James Phillips’ work is included in several well known collections as well as numerous private collections. His works have been specially created for public art projects for the city of Baltimore, Howard University in Washington, DC, the Department of Parks in New York City and the transit system for San Francisco, California and is highly collected by individuals throughout the nation.

In 2014 James Phillips' Sankofa II was added to the Smithsonian Institution's permanent art collection. The painting will be displayed in the National Museum of African Amerian History and Culture, scheduled to open in 2016.

In 2006, the Art in Embassies Program of the United States Department of State purchased two of Phillips’ paintings Water Spirits and Rainbow for Charles for the American Embassy in Togo.

In 1995 Hampton University acquired a piece of his work entitled Soul and Spirit of John Biggers for their permanent collection.

And in 1994 Phillips was commissioned by the Philadelphia Airport to create a permanent piece of art for their domestic wing. A triptych of a stylized Airport situation with a flight tower, ground transportation, planes taking off and landing and stylized runways are incorporated into the body of the work and is entitled Gateways to The World.

Included in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Arts and Artifacts Collection of the New York City Public Library are two of Phillips’ works Black Unity (1972) and Deification of Shango (1994).

James Phillips currently lives in Baltimore, Maryland where he works from his studio located in his home. He also teaches painting and public art in the Department of Fine Arts at Howard University, Washington, DC. Since 1976 he has been both a mural consultant and a lecturer.

Bio courtesy of www.jamesphilips-artist.com

http://www.jamesphillips-artist.com/About_Me.html

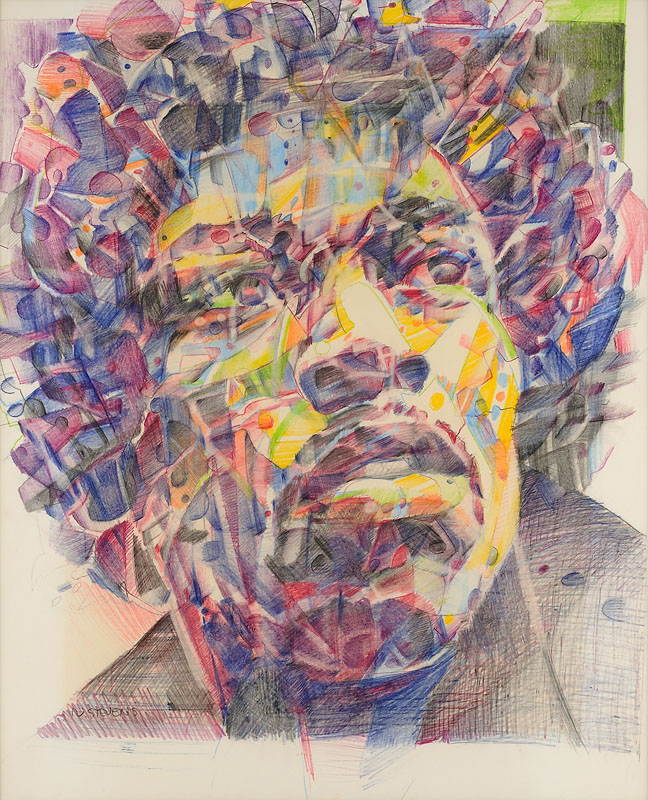

Visual Manifestation of Ashe (Life Force)

Oil on canvas

96x48 inches

1970

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Robert Pious (1908-1983)

Robert Savon Pious was born on March 7, 1908 in Meridian, Mississippi. His father, Nattie Pious, was born 1872 in Mississippi. His mother, Loula Pious, was born 1874 in Alabama. Both of his parents were the children of African-American slaves. His parents married in 1895 and had nine children, of which he was the sixth born. The family lived at 2005 18th Avenue in Meridian.

In 1927 he began to attend the Art Institute of Chicago, while he also worked full-time at nights in the press room of a massive Chicago printing plant, the Cuneo Press. While working with printed media he became interested in a career as a newspaper cartoonist and advertising artist.

He began to draw black and white illustrations for Continental Features, a supplier of material for newspapers catering to African-American readers. He continued to contribute editorial cartoons, advertisements and illustrations to this company for rest of his life.

In 1928 he married his wife, Ruth G. Mitchell, who was born 1909 in Chicago. She was a freshman at a college in Chicago. The newlyweds moved to 6352 Langley Avenue in Chicago.

In 1929 he completed his second year of study at the Art Institute of Chicago, but left school to work as a freelance commercial illustrator.

Along with his steady but low-paying work for Continental Features he also painted portraits of celebrities, entertainers, and the high society of Chicago's booming African-American community.

In 1929 one of his portraits won a prestigious award from the Harmon Foundation in New York City. This official recognition helped to promote his reputation as a promising artist.

In 1931 he was awarded a four-year scholarship to study at the National Academy of Design in New York City. He moved to Manhattan and lived at 446 St. Nicholas Avenue, near 133th Street in Harlem. After completing her second year of college in Chicago his wife quit school and joined him in NYC.

His portraits of noteworthy African-Americans soon appeared on covers of Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life.

While living in Harlem during the Great Depression he met the sculptress, Augusta Savage (1892-1962), whose studio was a popular fixture in the Harlem Artists Guild. There he met other important artists from the Harlem Renaissance art movement, such as Ernest Chrichlow (1914-2005), Charles Alston (1907-1977), Norman Lewis (1901-1979), Joseph Delaney (1904-1991), Romare Beardon (1911-1988), and Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000).

At that same time he also met Charles C. Seifert (1871-1949), a scholar of African history, who became the artist's mentor and inspired him to explore historic subjects of African ancestry.

During the 1930s he worked as a muralist for the WPA Federal Art Project, an enlightened government program that provided relief income for artists. Pulp artists George Avison, Delos Palmer, Elton Fax, Lee Browne Coye, and Remington Schuyler also worked on mural projects for this same government program. Robert Pious worked on murals in several libraries, health centers, and schools in NYC, such as the DeWitt Clinton High School. He was also funded by the W.P.A. to teach art at the Harlem branch of the Y.M.C.A.

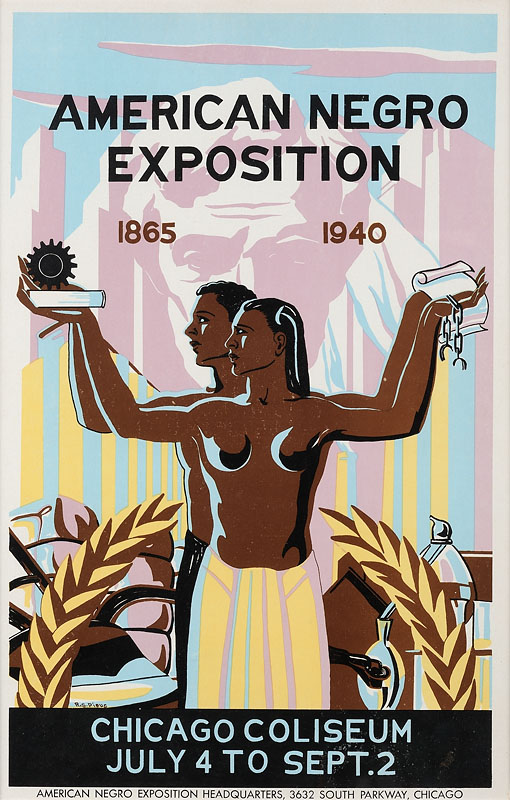

In 1936 he designed the poster for the world's fair, The Texas Centennial Exposition, which was held in Dallas and included a Hall of Negro Life, one of the earliest mainstream celebrations of African-American history.

In 1940 he won first prize in a poster competition for his design for The American Negro Exposition, which marked the jubilee of the abolition of slavery. The award was presented to him at City Hall by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia.

During the 1940s Robert Pious was an artist celebrity, whose activities were reported in the African-American media along with popular athletes, entertainers, business tycoons and socialites.

During WWII he worked under contract as an illustrator for the Office of War Information.

From 1943 to 1949 his pen and ink drawings appeared as story illustrations in pulp magazines. His work appeared in Sky Raiders, Exciting Sports, Exciting Football, Popular Football, Sports Fiction, Super Sports and Sports Winners.

From 1940 to 1953 worked for many golden age comic book publishers, such as Street & Smith, Fiction House, Ace Periodicals, Archie, Chesler Studio, Novelty Comics and Victory Comics.

In the 1950s he illustrated books for several publishers, including Grosset & Dunlap, Whitman Publishing, Harvey House, Random House, Funk & Wagnalls, and Bobbs-Merrill Publishing Company.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s his portraits appeared regularly on covers of the National Scene, a weekly magazine distributed nationwide as a Sunday supplement in many African-American newspapers.

His artistic achievements brought him even wider recognition and celebrity in his final years. He was popular enough to appear in an advertised product endorsement for Lucky Strike cigarettes.

His portrait of Harriet Tubman is displayed at the Smithsonian Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Robert S. Pious died in the Bronx at the age of seventy-four on February 1, 1983.

Bio courtesy of www.pulpartists.com link to full bio: https://www.pulpartists.com/Pious.html

American Negro Exposition 1865-1940

Serigraph

21x13 inches

1940

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Rose Piper (1917-2005)

Rose Theodora Piper (October 7, 1917 – May 11, 2005) was an American painter best known for her semi-abstract, blues-inspired paintings of the 1940s. In the 1950s, out of financial necessity, she became a textile designer. For nearly thirty years, she worked as Rose Ransier, designing knit fabrics.

The American public took note of her work in the fall of 1947 when she gave her first solo exhibition—titled Blues and Negro Folk Songs—at the Roko Gallery in New York. The exhibition featured 14 paintings based on folk and blues songs. The show was very successful and was lauded by art critics; due to its resounding success, the show was held over for an extra week, and the vast majority of the paintings were sold. At the time Piper was one of only four African-American abstract painters to have had solo shows in New York. After retiring from textile design, she resumed painting and exhibiting in the 1980s.

Rose Piper was born Rose Theodora Sams in New York on October 7, 1917. She grew up in the Bronx, where her father was a public schoolteacher who taught Latin and Greek. She attended Hunter College, majoring in art and minoring in geometry, and graduated in 1940. From 1943 to 1946, she attended the Art Students League of New York, where she studied with Vaclav Vytlacil and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. It was during this period that the poet Myron O'Higgins introduced her to Sterling Brown, who encouraged her growing interest in blues music.[1] Brown was the author of "Ma Rainey" (1932), arguably the quintessential blues poem;[2][3] O'Higgins, his student at Howard University, had also written poetry on blues themes, such as "Blues for Bessie" (1945).[4]

In 1946 she received a Julius Rosenwald fellowship and spent the summer traveling in the American South, "imbibing" the atmosphere, as she put it, and studying blues music.[1] As a New Yorker, she had not grown up listening to the blues; she said in an interview years later, "I ran out and got all kinds of recordings and listened to them. I worked at it." Her research inspired a series of increasingly abstract, blues-themed paintings. Back Water (1946), inspired by Bessie Smith's "Backwater Blues",[3] is more figurative and literal in its approach than the paintings that followed. By 1947, Piper had adopted the Picasso-influenced, flat, geometric style seen in Slow Down, Freight Train and The Death of Bessie Smith (pictured right).[5]

According to critic Graham Lock, this semi-abstract style was a fitting choice for the series because the blues themselves are stylized, often using exaggeration (such as "pouring water on a drowning man") to convey strong emotions.[6] Piper never embraced pure abstraction, however, preferring to keep the human figure at the center of her work. Her purpose in creating art was political: to fight injustice "the best way I know how—by putting it on the canvas."[5]

Her work attracted national attention in the fall of 1947 when she gave her first solo exhibition at the Roko Gallery in New York. Titled Blues and Negro Folk Songs, the exhibition featured 14 paintings based on folk and blues songs. The show was a major success: praised by critics, it was held over for an extra week, and most of the paintings were sold.[1] At that time she was one of only four African-American abstract painters to have had solo shows in New York. The other three were Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, and Thelma Johnson Streat.[7]

She scored another win in 1948 when her work was included in the 7th Annual Exhibition of Paintings, Sculpture and Prints by Negro Artists. Sponsored by Atlanta University, it was one of the most prestigious venues for black artists; fellow exhibitors included Richmond Barthé, Robert Blackburn, Jacob Lawrence, and Hale Woodruff. Piper's Grievin' Hearted was awarded the prize for Best Portrait or Figure Painting.[1]

Piper, alongside artist such as Elder Cortor, produced images during the 1940s that illuminated the constant contemporary problems related to women's control over their bodies within social, racial, and sexual milieux.[8]

Piper's career peaked in the late 1940s. She kept a studio in Greenwich Village, and exhibited in the ACA Gallery.[9] Her work was reviewed in the New York Times, Art Digest, and ARTnews.[10] Her circle of acquaintances included James Baldwin, Billie Holiday, and Langston Hughes. Charles Alston was a friend and mentor. Recalling those years in a 1989 interview, she said, "I had the greatest time. The world was at my feet."[1]

While it is not clear whether Slow Down, Freight Train was painted in 1946 or 1947, this painting represents a very different aesthetic approach to that of Back Water. This is Piper at her most semiabstract. When the Ackland Art Museum acquired the work in 1990, director Charles Millard wrote to Piper, enquiring about the origins of the title. The title referred to "Freight Train Blues" a recording by Trixie Smith, who "sang and recorded the misery of the woman who bad been left behind by men who hopped freight trains to the North"[11]

Even as her blues-themed paintings won her attention and acclaim, Piper was wary of being stereotyped as a black painter limited to "black" themes. It was partly for this reason that, on receiving a second Rosenwald grant in 1948, she opted to work in Paris rather than continue her exploration of the American South.[12]

When Piper returned from Paris, a series of financial and family misfortunes forced her to put her painting career on hold. For a time she ran her own greeting card business. She then worked as a textile designer, using the name Rose Ransier. Over the next three decades she built a successful, albeit anonymous, career in fashion, while raising her two children and caring for ailing family members. Her minor in geometry gave her an edge in her new line of work: she was able to design patterns on graph paper that did not need to be adjusted for the knitwear machines. In 1973, she won the Knitted Textile Association's First Annual Knit Competition. When she retired in 1979, she was a senior vice president.[13]

In the 1980s, Piper returned to painting. This time she adopted a whole new style, influenced by her years in textile design: instead of semi-abstraction and a subdued, melancholy palette, the later paintings combined a meticulous attention to detail and bright acrylics. As influences, she cited Flemish School painters Hans Memling and Jan van Eyck, and the medieval Book of Hours tradition.[14]

She still drew inspiration from African-American music, and her sense of political purpose had not changed. In 1989 she had a solo exhibition in New York, sponsored by the Phelps Stokes Fund. The centerpiece, titled Slave Song Series, was a set of ten 12 x 9 inch miniatures based on lines from spirituals. Half were set in contemporary urban locales; for example, I Want Yuh to Go Down, Death, Easy / An' Bring My Servant Home (pictured right) is set in the 96th Street subway station. Describing her motivation for the series, she wrote that "the current state of many inner-city blacks is not unlike the desperate situation of the slave ancestors."[15]

Piper died of a stroke on May 11, 2005 in a Connecticut nursing home, aged 87.[14]

Bio courtesy of www.wikipedia.com. Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rose_Piper

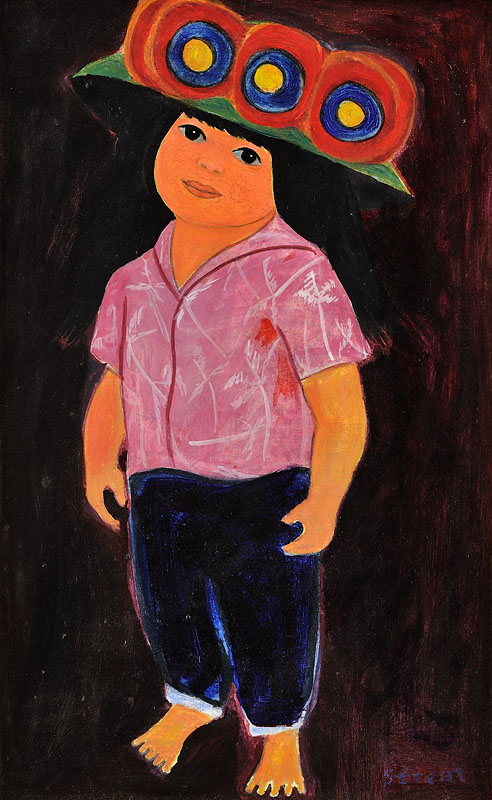

Blues Singer

Mixed media on paper

24 1/2x29 inches

1989

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

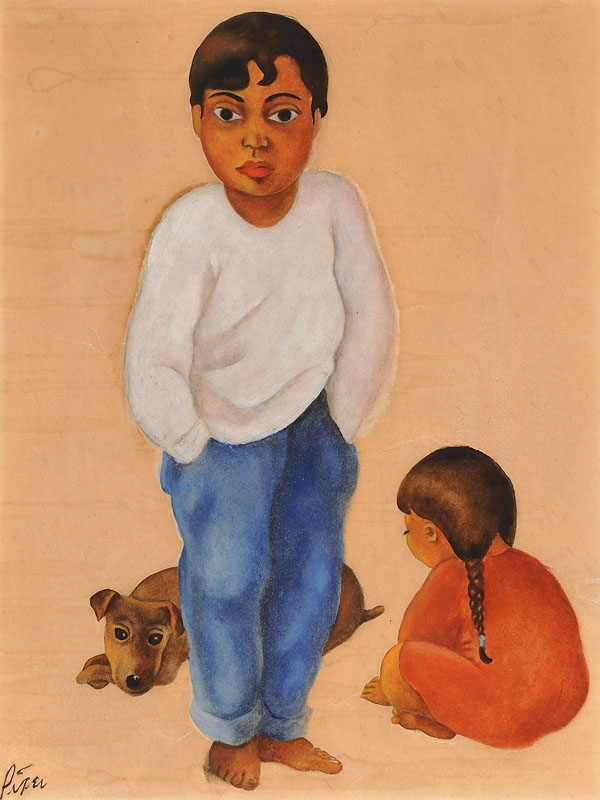

Mexican Girl and Boy with Dog

Mixed media with watercolor and crayon

12x9 inches

c. 1950

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

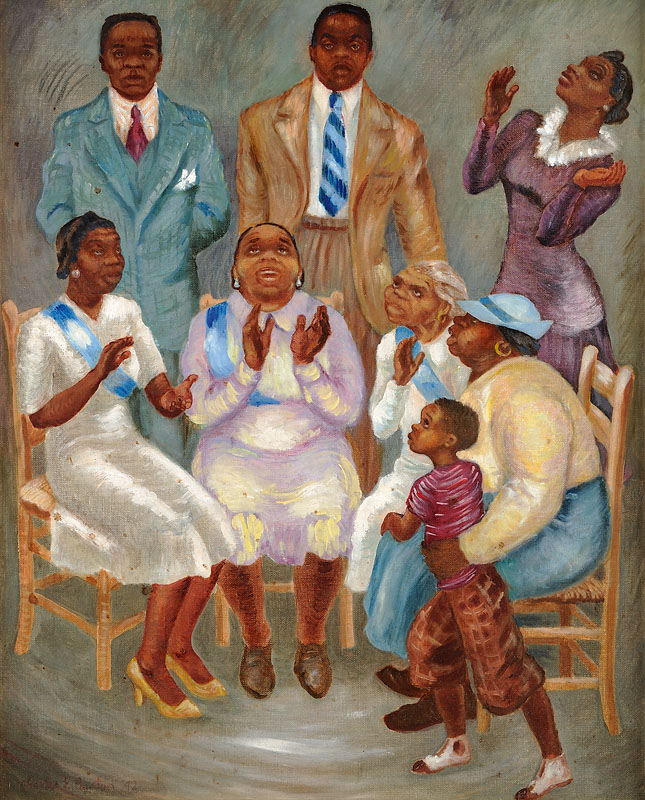

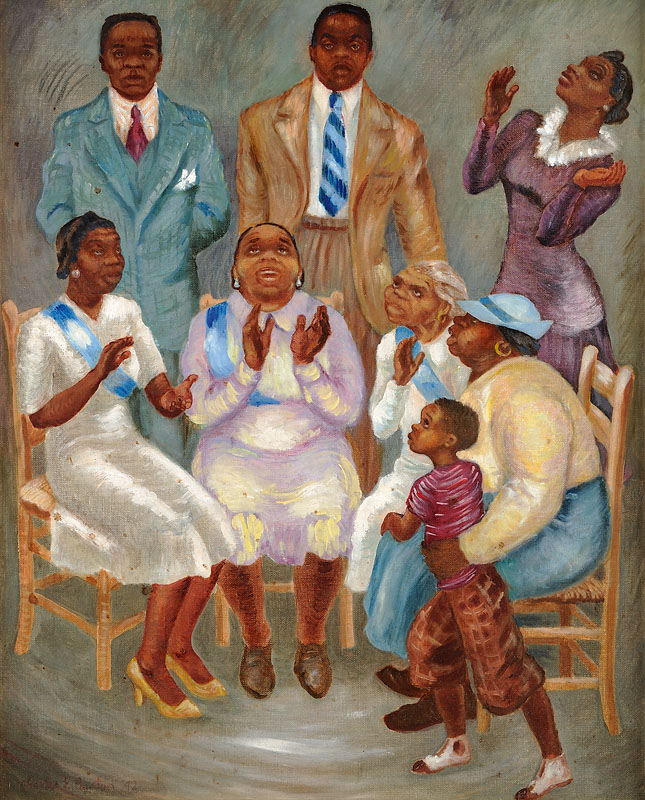

Charles Preston

Members of the Church

Oil on canvas

24x20 inches

1942

Signed and dated

Ramon Price

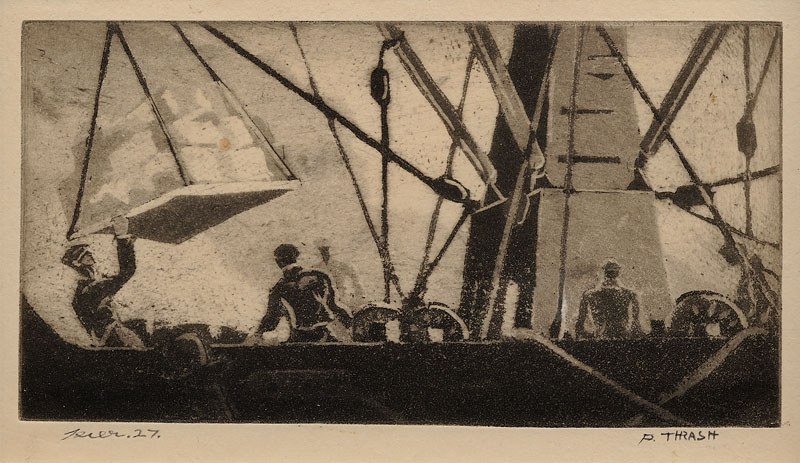

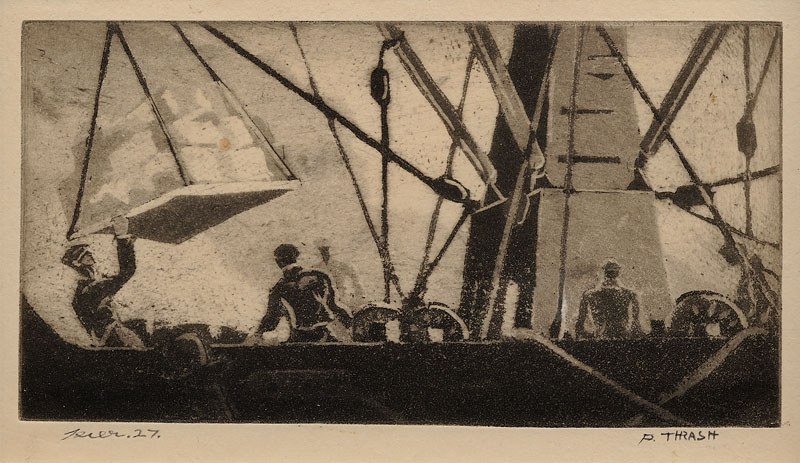

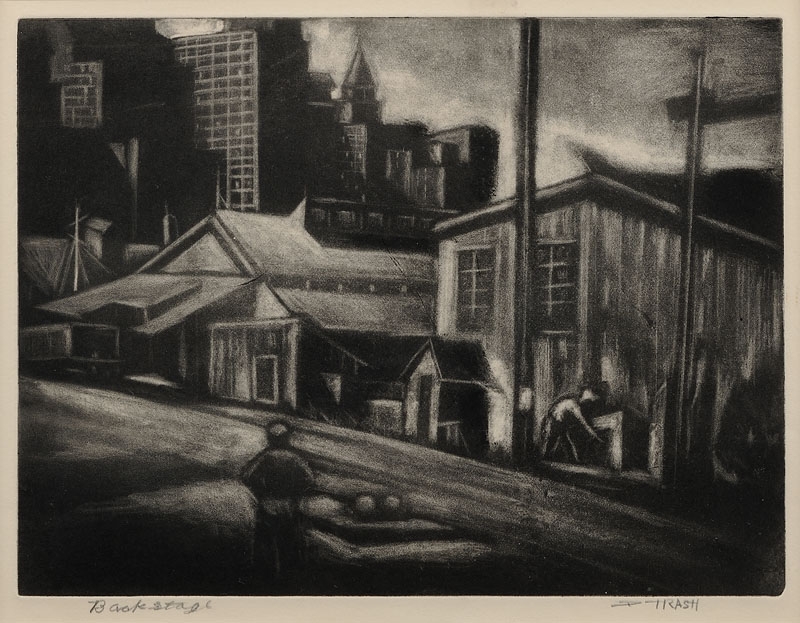

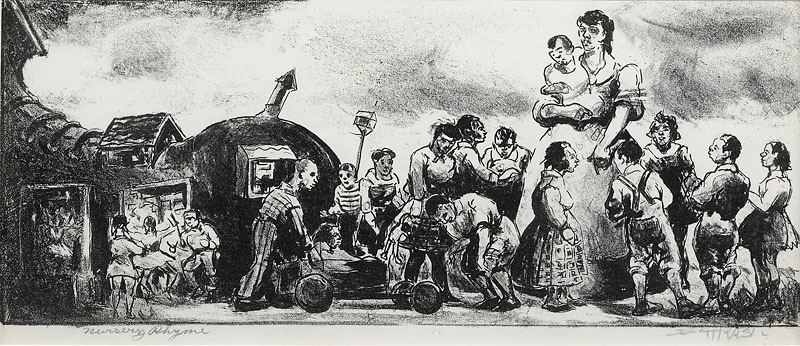

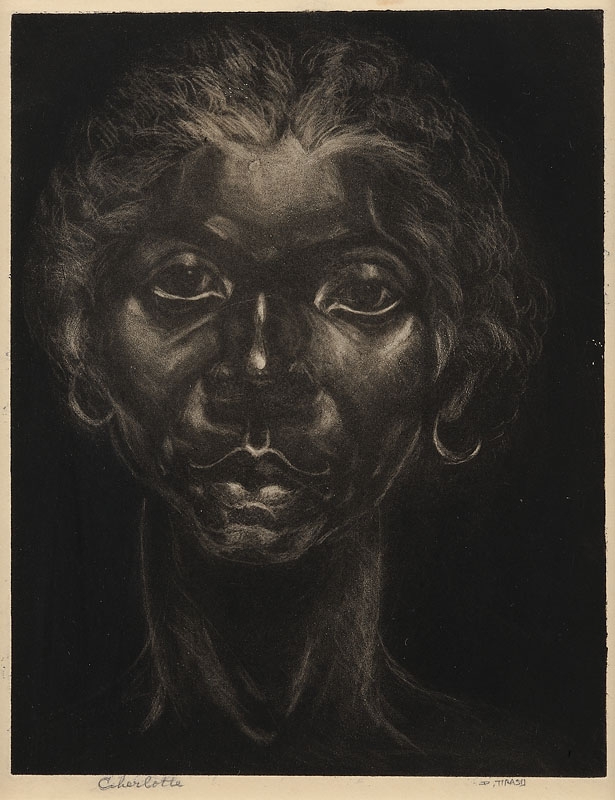

Tacking Against the Wind

Serigraph

8x10 inches

Year unknown

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Nelson A. Primus (1842-1916)

Landscape with Horse

Oil on board

18x24 inches

1884

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

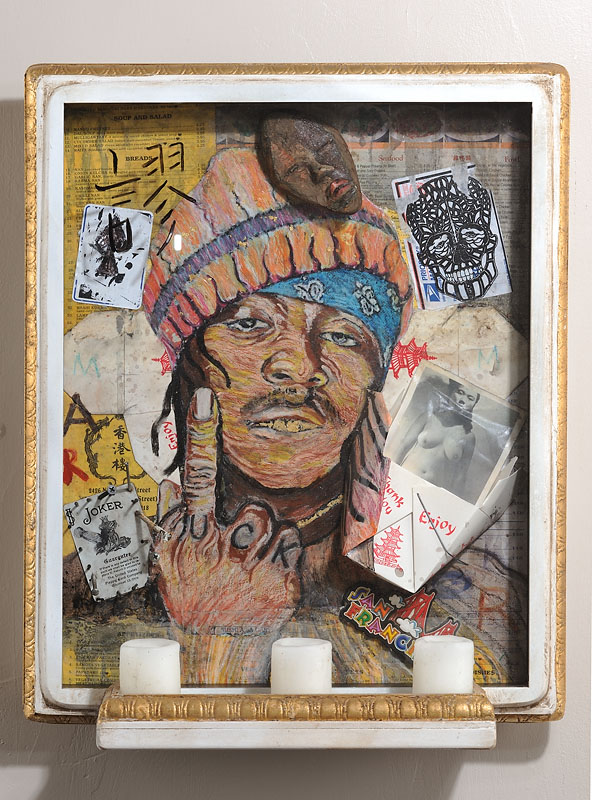

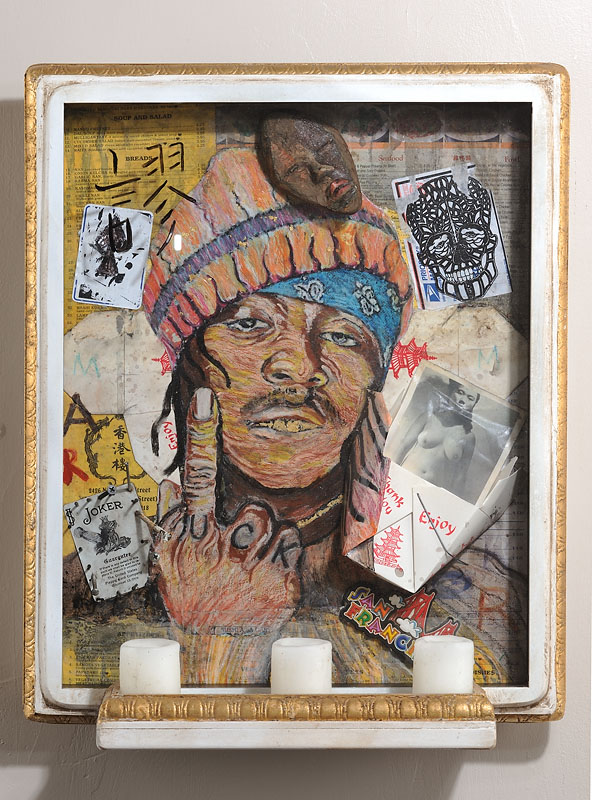

William Rhodes

Falsehood, The Last Patron Saint of the Bayview

Mixed media assemblage

22 1/2x18x6 1/2 inches

Year unknown

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

William Richard

Gregory Ridley Jr. (1925-2004)

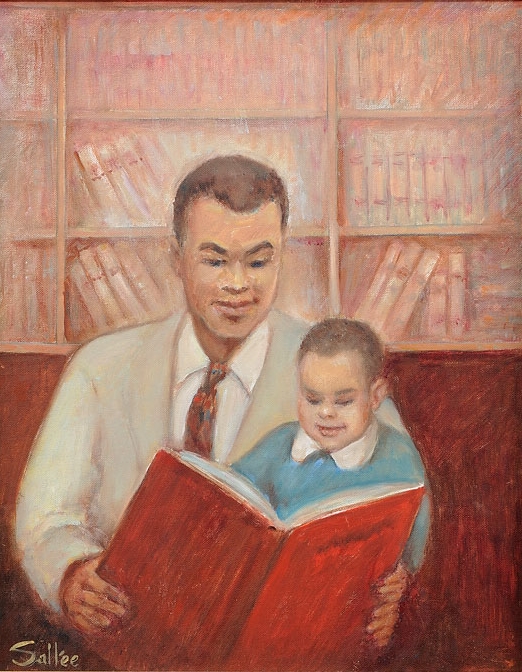

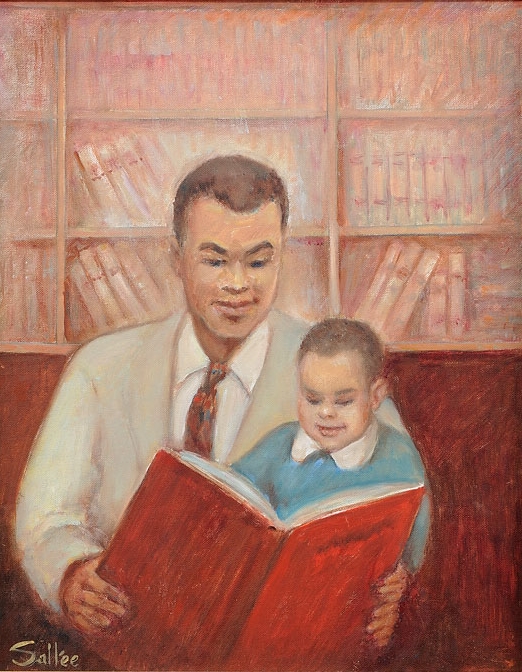

Charles Sallee Jr. (1913-2006)

The first African American to graduate from the Cleveland School of Art (now Cleveland Institute of Art), Sallee worked as a printmaker and, during the Depression, a muralist for the Works Progress Administration. He was the leader of the Karamu Group of printmakers, formed by artists connected to the Karamu House, an African American theater and community center that premiered many of Langston Hughes’s plays. In his prints, Sallee frequently depicted scenes of urban labor and the black experience in northern cities.

Bio courtesy of http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/491388

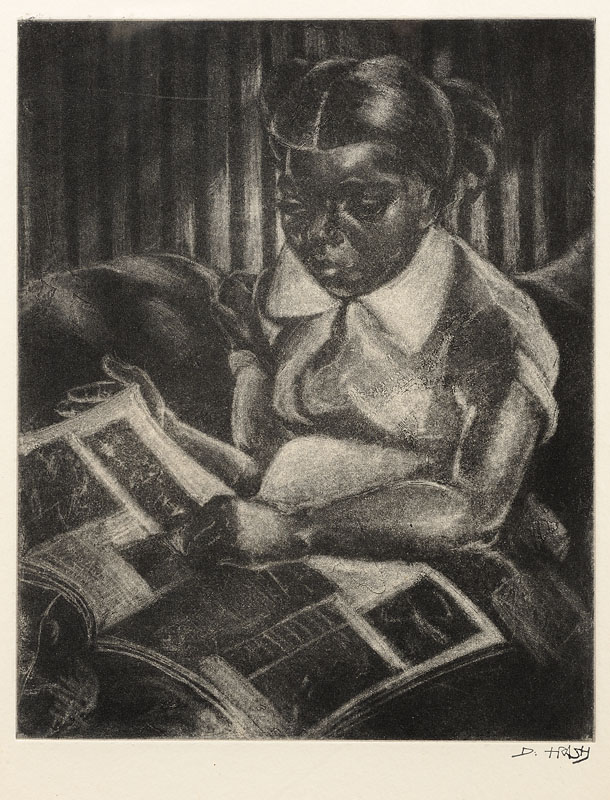

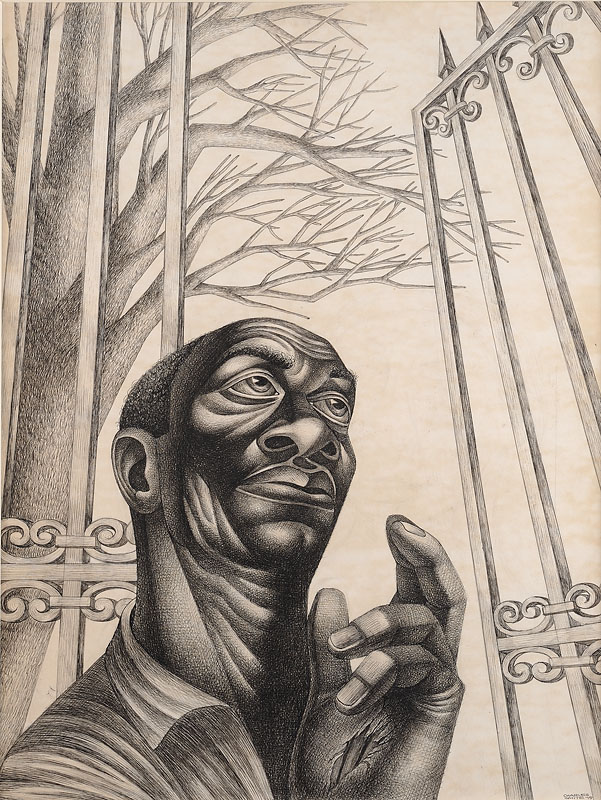

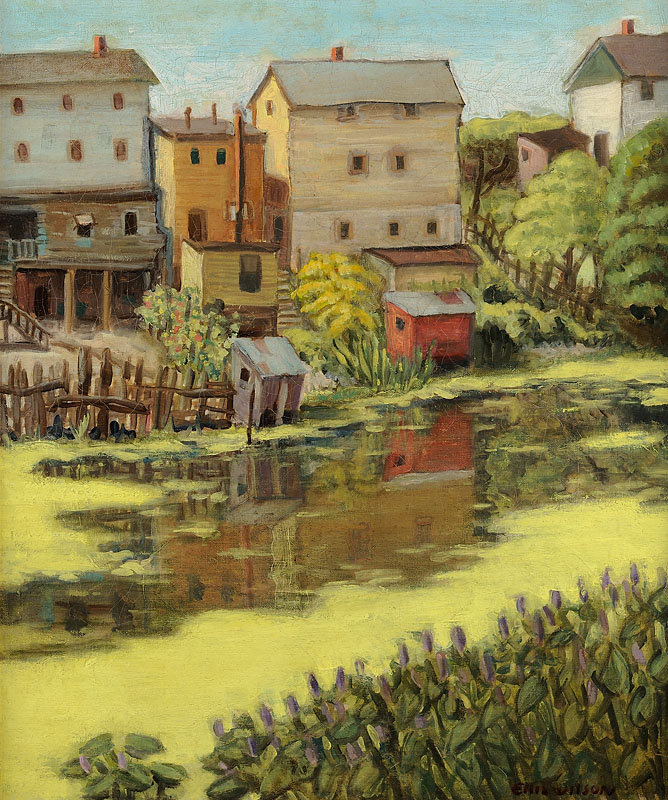

The Reading Lesson

Oil on canvas board

19 1/2x15 1/2 inches

1971

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Augusta Savage (1892-1962)

Augusta Fells (Savage) was born in Green Cove Springs (near Jacksonville), Florida, on February 29, 1892, to Edward Fells, a Methodist minister, and Cornelia Murphy.[2] She began making clay figures as a child, mostly small animals, but her father was a poor Methodist minister who strongly opposed his daughter’s early interest in art. "My father licked me four or five times a week,” Savage once recalled, “and almost whipped all the art out of me.”[3] This was because at that time, he believed her sculpture to be a sinful practice, based upon his interpretation of the "graven images" portion of the Bible.[4] She persevered, and the principal of her new high school in West Palm Beach, where her family relocated in 1915,[5] encouraged her talent and allowed her to teach a clay modeling class.[4] This began a lifelong commitment to teaching as well as to art.

In 1907, Augusta Fells married John T. Moore. Her only child, Irene Connie Moore, was born the next year. John died shortly thereafter.[5] In 1915, she married James Savage;[6][7] she kept the name of Savage throughout her life. After their divorce in the early 1920s, Augusta Savage moved back to West Palm Beach.[5]

Augusta Savage continued to model clay, and in 1919 was granted a booth at the Palm Beach County Fair, where she was awarded a $25 prize and ribbon for most original exhibit.[5] Following this success, she sought commissions for work in Jacksonville, Florida, before departing for New York City in 1921.[5] She arrived with a letter of recommendation from Palm Beach County Fair official, George Graham Currie, for sculptor Solon Borglum and $4.60.[4] Borglum declined to take her as a student, but encouraged her to apply to Cooper Union in New York City, where she was admitted in October, 1921. She was selected before 142 other women on the waiting list.[8] Her talent and ability so impressed the Cooper Union Advisory Council that she was awarded additional funds for room and board when she lost the financial support of her job as an apartment caretaker.[5] From 1921 through 1923, she studied under sculptor George Brewster.[4]She completed the four-year course of study degree in three years.[2]

In 1923, Savage applied for a summer art program sponsored by the French government; although being more than qualified, she was turned down by the international judging committee, solely because she was black.[9] Savage was deeply upset, and questioned the committee, beginning the first of many public fights for equal rightsin her life. The incident got press coverage on both sides of the Atlantic, and eventually the sole supportive committee member, sculptor Hermon Atkins MacNeil—who at one time had shared a studio with Henry Ossawa Tanner—invited her to study with him. She later cited him as one of her teachers. After completing studies at Cooper Union, Savage worked in Manhattan steam laundries to support herself and her family. Her father had been paralyzed by a stroke, and the family's home destroyed by a hurricane. Her family from Florida moved into her small West 137th Street apartment. During this time she obtained her first commission, for a bust of W. E. B. Du Bois for the Harlem Library. Her outstanding sculpture brought more commissions, including one for a bust of Marcus Garvey. Her bust of William Pickens, Sr., a key figure in the NAACP, earned praise for depicting an African-American in a more humane, neutral way as opposed to stereotypes of the time, as did many of her works.[10]

In 1923, Savage married Robert Lincoln Poston, a protégé of Garvey.[11] Poston died of pneumonia aboard a ship while returning from Liberia as part of a Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League delegation in 1924.

In 1925, Savage won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rome; the scholarship covered only tuition, however, and she was not able to raise money for travel and living expenses. Thus she was unable to attend. In the 1920s writer and eccentric Joe Gould became infatuated with Savage. He wrote her "endless letters", "telephoned her constantly", and wanted to marry her. Eventually this turned to harassment.[12]

Knowledge of Savage's talent and struggles became widespread in the African-American community; fund-raising parties were held in Harlem and Greenwich Village, and African-American women's groups and teachers from Florida A&M all sent her money for studies abroad. In 1929, with assistance as well from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, Savage enrolled and attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, a leading Paris art school. In Paris, she studied with the sculptor Charles Despiau.[13] She exhibited and won awards in two Salons and one Exposition. She toured France, Belgium, and Germany, researching sculpture in cathedrals and museums.

Savage returned to the United States in 1931, energized from her studies and achievements. The Great Depression had almost stopped art sales. She pushed on, and in 1934 became the first African-American artist to be elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. She then launched the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, located in a basement on West 143rd Street in Harlem. She opened her studio to anyone who wanted to paint, draw, or sculpt. Her many young students would include the future nationally known artists Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis, and Gwendolyn Knight. Another student was the sociologist Kenneth B. Clark, whose later research contributed to the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that ruled school segregation unconstitutional. Her school evolved into the Harlem Community Art Center; 1500 people of all ages and abilities participated in her workshops, learning from her multi-cultural staff, and showing work around New York City. Funds from the Works Progress Administration helped, but old struggles of discrimination were revived between Savage and WPA officials who objected to her having a leadership role.[14]

Savage received a commission from the 1939 New York World's Fair; she created Lift Every Voice and Sing (also known as "The Harp"), inspired by the song by James Weldon and Rosamond Johnson. The 16-foot-tall plaster sculpture was the most popular and most photographed work at the fair; small metal souvenir copies were sold, and many postcards of the piece were purchased. The work reinterpreted the musical instrument to feature 12 singing African-American youth in graduated heights as its strings, with the harp's sounding board transformed into an arm and a hand. In the front, a kneeling young man offered music in his hands.[15] Savage did not have funds to have it cast in bronze, or to move and store it. Like other temporary installations, the sculpture was destroyed at the close of the fair.[15]

Savage opened two galleries, whose shows were well attended and well reviewed, but few sales resulted, and the galleries closed. Deeply depressed by the financial struggle, in the 1940s Savage moved to a farm in Saugerties (near Woodstock, New York), where she stayed until 1960. She worked on a mushroom farm, and made little or no effort to talk about or create art. Her few neighbors said that she was always making something with her hands.[16]

Much of her work is in clay or plaster, as she could not often afford bronze. One of her most famous busts is titled Gamin, which is on permanent display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.; a life-sized version is in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. At the time of its creation, Gamin, which is modeled after a Harlem youth, was voted most popular in an exhibition of over 200 works by black artists.[17] Her style can be described as realistic, expressive, and sensitive. Though her art and influence within the art community is documented, the location of much of her work is unknown.

In 1945, Savage retired from the art world. She taught art to children and wrote children's stories before she died.[2] Savage died of cancer on March 26, 1962, in New York City. While she was all but forgotten at the time of her death, Savage is remembered today as a great artist, activist and arts educator, serving as an inspiration to the many that she taught, helped and encouraged.[15]

The Augusta Fells Savage Institute of Visual Arts, a Baltimore, Maryland public high school, is named in her honor.

In 2001, her home in Saugerties, New York, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Augusta Savage House and Studio.[18] In 2007 the City of Green Cove Springs, Florida nominated her to be inducted into the Florida Artist Hall of Fame; she was inducted the spring of 2008. Today, at the actual location of her birth there is a Community Center named in her honor.

A biography of Augusta Savage intended for younger readers has been written by author Alan Schroeder. In Her Hands: The Story of Sculptor Augusta Savage was released in September 2009 by Lee and Low, a New York publishing company.

Bio courtesy of www.wikipedia.com link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augusta_Savage

Lift Every Voice and Sing

Silver oxide

11x9 1/2x4 inches

1939

Inscribed ("Augusta Savage")

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Thomas Albert Sills (1914-2000)

Thomas Sills was born and raised in Castalia, North Carolina. Before he got involved with painting, he worked in a greenhouse in Raleigh, North Carolina, where the color around him made a strong impression on him. Once in New York, he worked on the docks, as a janitor, and as a deliveryman.[1]

Sills spent most of his creative life in New York City, deeply rooted in the artistic trends as well as cultural issues from the early 1950s to 1970s. He knew Willem de Kooning who visited his studio and told him not to throw anything away before anyone had seen it.

Others in the NY circle gave him advice. At the time of his first solo show, Barnett Newman sent him a letter of congratulations.[2] His friendships with Newman and Mark Rothko placed him at the intellectual center of the Abstract Expressionist movement, but like de Kooning, Arshile Gorky and Franz Kline, Sills believed that it was not necessary to explain his art; he painted what he felt and it came from within.[2]

Sills began his work as a fine artist when he was in his mid-thirties, about the time he married the mosaicist Jeanne Reynal. Essentially self-taught and inspired by Reynal's collection of abstract art, he began working with the materials he found in her mosaic studio, but soon branched out to oil on wood as well as canvas.

Through his exploratory approach to materials, Sills was able to release phantasmical abstract paintings. Intrigued by the light quality of mosaics, a similar luminosity emerged in Sill's bright oil compositions. His provocative handling of color and innovative use of media attracted the attention of the New York avant-garde.

Sills's regular presence in the art world of the 1950s through the early 1970s as an African-American painter situated him as an integral element of the mainstream and African-American art. Thomas Sills perceived his art to be beyond the political. He found in Art a form of expression for the dynamism that escapes any formal constraints. Sills' work was highly intuitive and he too sought inspiration from primitive art—in the 1950s he made frequent trips to Mexico to study the sculptures, frescos and architecture of Chiapas and the Yucatan.

At the peak of his career in the 1960s and 1970s, his work was widely shown in museums. He had four solo shows at Betty Parsons Gallery, was regularly featured in art journals and is in museum collections. Today, there is a renaissance of the popularity of his works. He is being exhibited in many shows, most recently African American Abstract Masters at the Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York and Abstraction Plus Abstraction at Wilmer Jennings Gallery at Kenkeleba, and Encore, Five Abstract Expressionists at Sidney Mishkin Gallery of Baruch College, The City University of New York in 2006.

His work has been acquired by over 30 museums, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and the Newark Museum.[1][3][4]

Bio courtesy of Wikipedia. Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Sills

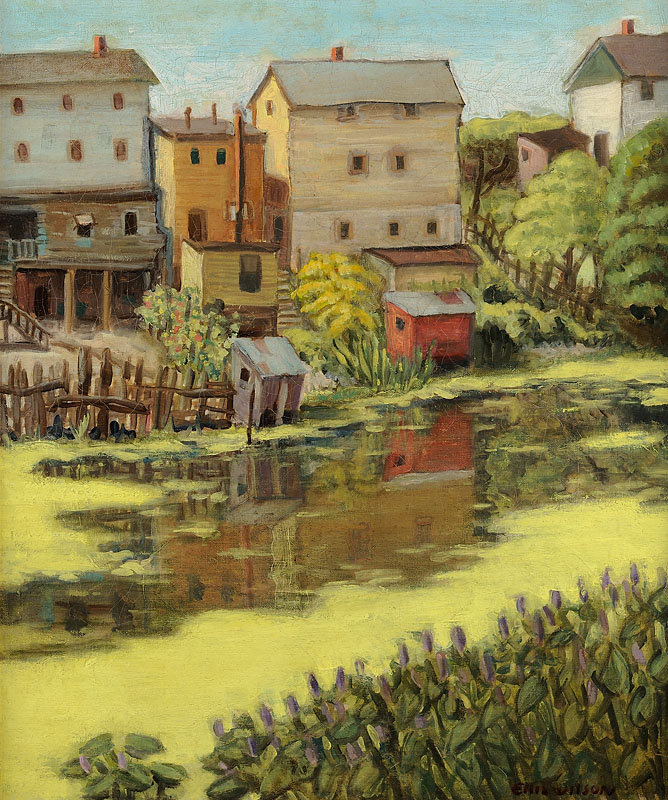

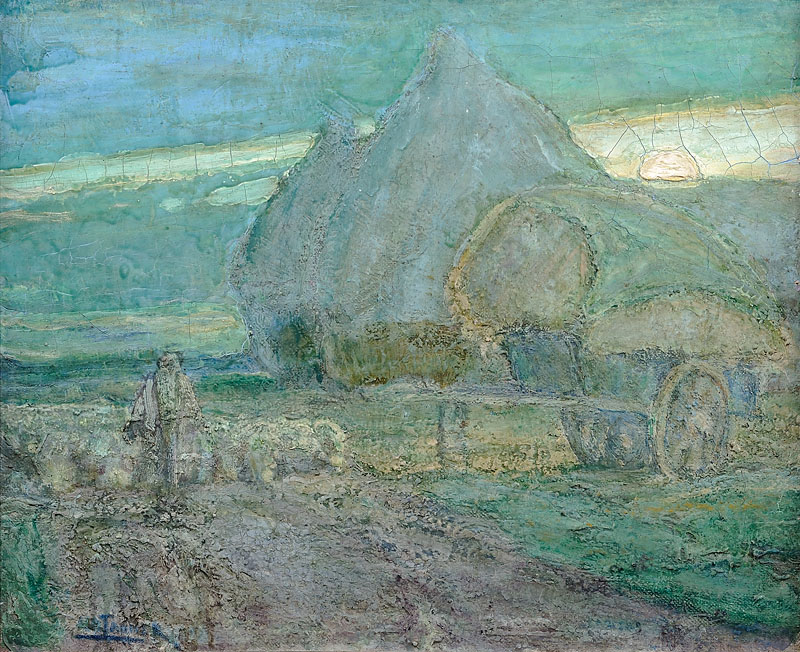

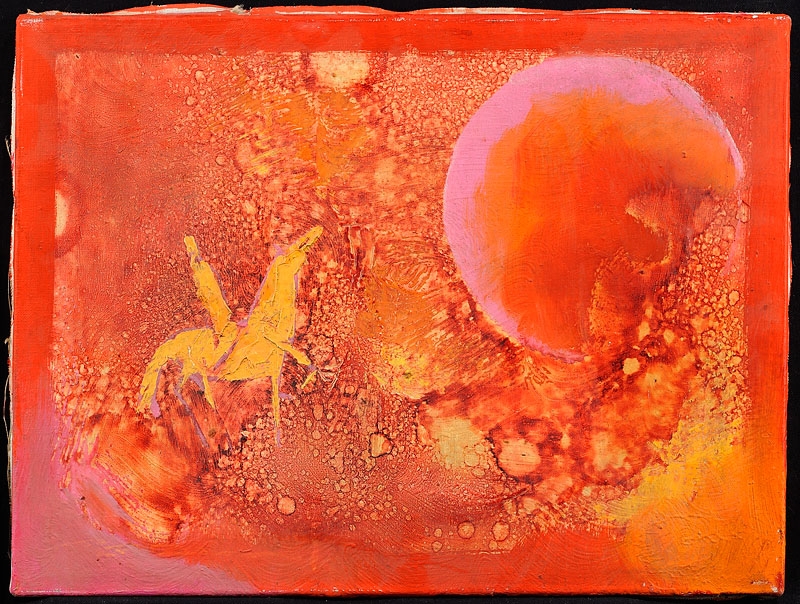

Pleasant Hills

Oil on canvas

42x49 inches

1966

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Lorna Simpson (b. 1960)

Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1960, she attended the High School of Art and Design and the School of Visual Arts in New York where she received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography. After receiving her BFA, she traveled to Europe and Africa, developing skills in documentary photography, her earliest works. While traveling, she became inspired to expand her work beyond the field of photography in order to challenge and engage the viewer.

It was these ideas that she worked on while earning her Master's of Fine Arts degree from the University of California at San Diego in 1985. Her education in San Diego was somewhere between Photography and Conceptual art, and her teachers included conceptualist Allan Kaprow, performance artist Eleanor Antin, filmmakers Babette Mangolte and Jean-Pierre Gorin and poet David Antin.[1] What emerged was her signature style of "photo-text", in which graphic text is inserted into studio-like portraiture, bringing new conceptual meaning into the works. These works generally related to the perception of African-American women within American culture. [2]

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Simpson was showing work through solo exhibitions all over the country, and her name was synonymous with photo-text artworks. She was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in 1985, and in 1990, she became the first African-American woman to exhibit at the Venice Biennale.[3] In 1990, Simpson had one woman exhibitions at several major museums, including the Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado, the Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.[4] [5] Simpson has explored various media and techniques, including two-dimensional photographs as well as silk screening her photographs on large felt panels, creating installations, or producing as video works such as Call Waiting (1997).[6]

By the 2000s she had started exploring the medium of video installations in order to avoid a paralysis brought on by outside expectations. In 2001 she was awarded the Whitney Museum of Art Award, and in 2007, her work was featured in a 20-year retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York City. [2]

Simpson continues to influence the legacy of black artists today by speaking with artists and activists such as the Art Hoe Collective, a group of young women using social media to give marginalized groups a safe platform to broadcast their artwork. [7]

In 2016 Simpson created the album artwork for Black America Again by Common. During the same year, she was featured in the book In the Company of Women, Inspiration and Advice from over 100 Makers, Artists, and Entrepreneurs. [8]In a 2017 issue of Vogue Magazine, Simpson showcased a series of portraits of 18 professional creative women who hold art central to their lives. The women photographed included Teresita Fernández, Huma Bhabha, and Jacqueline Woodson. Inspired by their resilience, Simpson said of these women, "They don't take no for an answer". [9]

Simpson's work has been displayed at the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Miami Art Museum, the Walker Art Center, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the Irish Museum of Modern Art.[10] In 2007, Simpson had a 20-year retrospective of her work at the Whitney Museum of American Art in her hometown of New York City.[6][11]

Simpson first came to prominence in the 1980s for her large-scale works that combined photography and text and defied traditional conceptions of sex, identity, race, culture, history, and memory. Drawing on this work, she started to create large photos printed on felt that showed public but unnoticed sexual encounters. Recently, Simpson has experimented with film as well as continuing to work with photography.[10]

Simpson's 1989 work, Necklines, shows two circular and identical photographs of a black woman's mouth, chin, neck, and collar bone. The white text, “ring, surround, lasso, noose, eye, areola, halo, cuffs, collar, loop”, individual words on black plaques, imply menace, binding or worse. The final phrase, text on red “feel the ground sliding from under you,” openly suggests lynching, though the adjacent images remain serene, non-confrontational and elegant.[12]

Easy for Who to Say, Simpson's work from 1989, displays five identical silhouettes of black women from the shoulders up wearing a white top that is similar to women portrayed in other of Simpson's works. The women's faces are obscured by a white-colored oval shape each with one of the following letters inside: A, E, I, O, U. Underneath the corresponding portraits are the words: Amnesia, Error, Indifference, Omission, Uncivil. In this work Simpson alludes to the racialization in ethnographic cinema and the revocation of history faced by many people of color. [13]

Simpson's work Guarded Conditions, created in 1989, was one in a series in which Simpson has assembled fragmented Polaroid images of a female model whom she has regularly collaborated with. The body is fragmented and viewed from behind, while the back of the model's head is sensed as being in a state of guardedness towards possible hostility she can anticipate as a result of the combination of her sex and the color of her skin. The complex historical and symbolic associations of African-American hairstyles are also brought into play. The message of the text and the formal treatment of the image reinforce a sense of vulnerability. The fragmentation and serialization of bodily images disrupts and denies the body's wholeness and individuality. In attempting to read the work the viewer is provoked into confronting histories of appropriation and consumption of the black female body.[14]

Simpson's work often portrays black women combined with text to express contemporary society's relationship with race, ethnicity and sex. In many of her works, the subjects are black women with obscured faces, causing a denial of gaze and the interaction associated with visual exchange. Through repetitive use of the same portrait combined with graphic text, her "anti-portraits" have a sense of scientific classification, addressing the cultural associations of black bodies. [15]

In a 2003 video installation, Corridor, Simpson sets two women side-by-side; a household servant from 1860 and a wealthy homeowner from 1960.[16] Both women are portrayed by artist Wangechi Mutu, allowing parallel and haunting relationships to be drawn.[11] She has commented, "I do not appear in any of my work. I think maybe there are elements to it and moments to it that I use from my own personal experience, but that, in and of itself, is not so important as what the work is trying to say about either the way we interpret experience or the way we interpret things about identity."[6]

Bio courtesy of Wikipedia. Link to full bio: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorna_Simpson

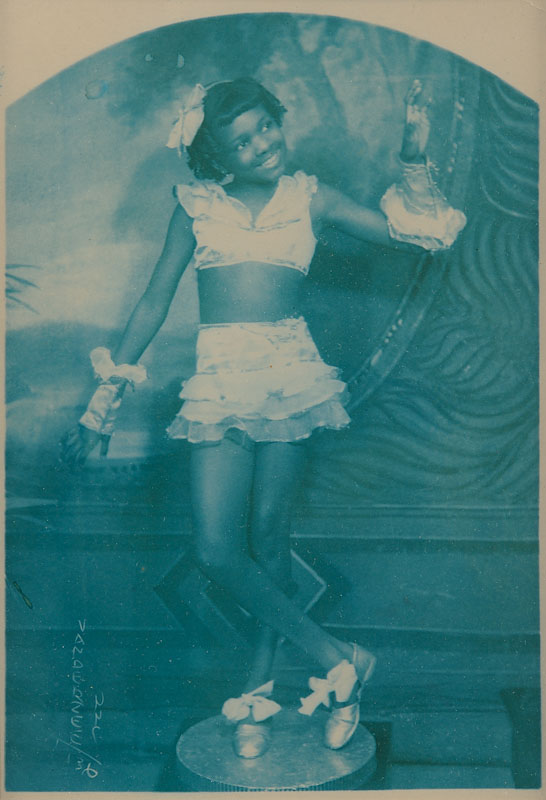

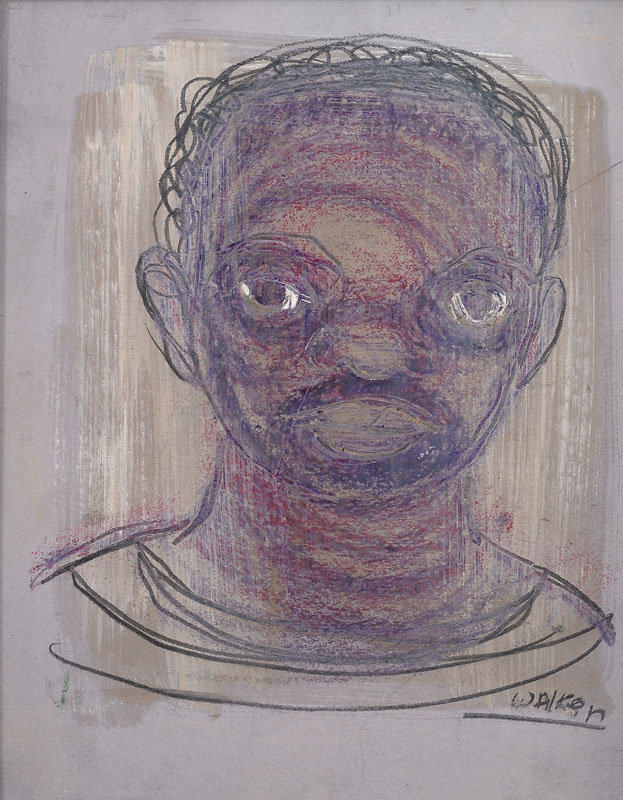

Self Portrait

Silver gelatin print

14x10 inches

1982

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

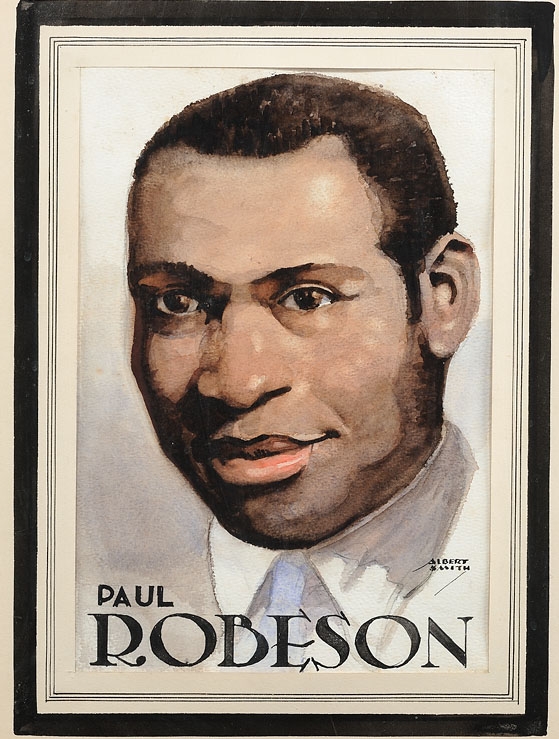

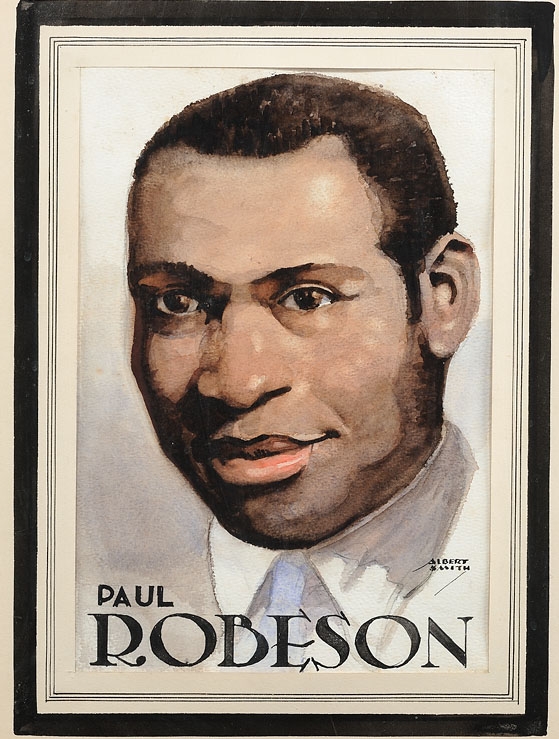

Albert Alexander Smith (1896-1940)

Paul Robeson

Watercolor

15x11 inches

c. 1920

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Self Portrait

Watercolor

12x9 inches

1920

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Self Portrait

Lithograph

15x11 inches

1928

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

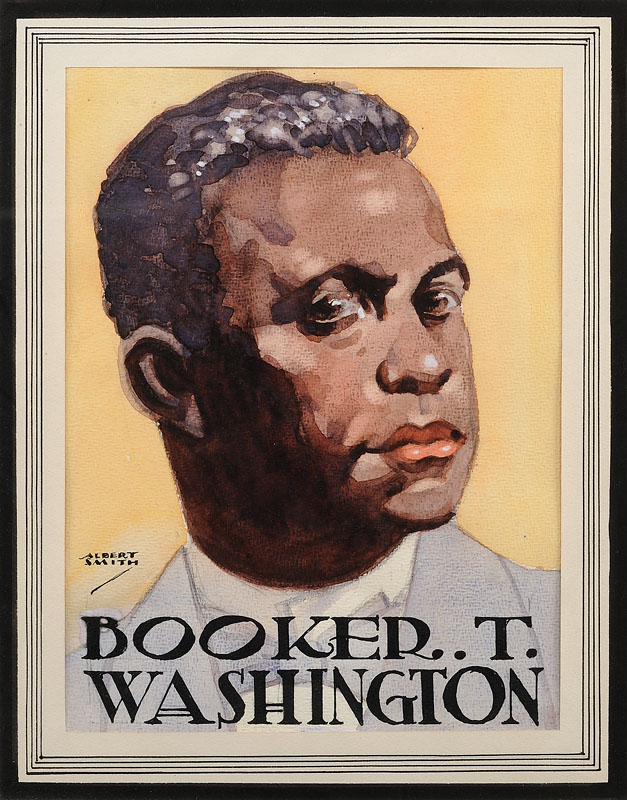

Booker T. Washington

Watercolor

11 1/4x8 1/2 inches

c. 1920

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

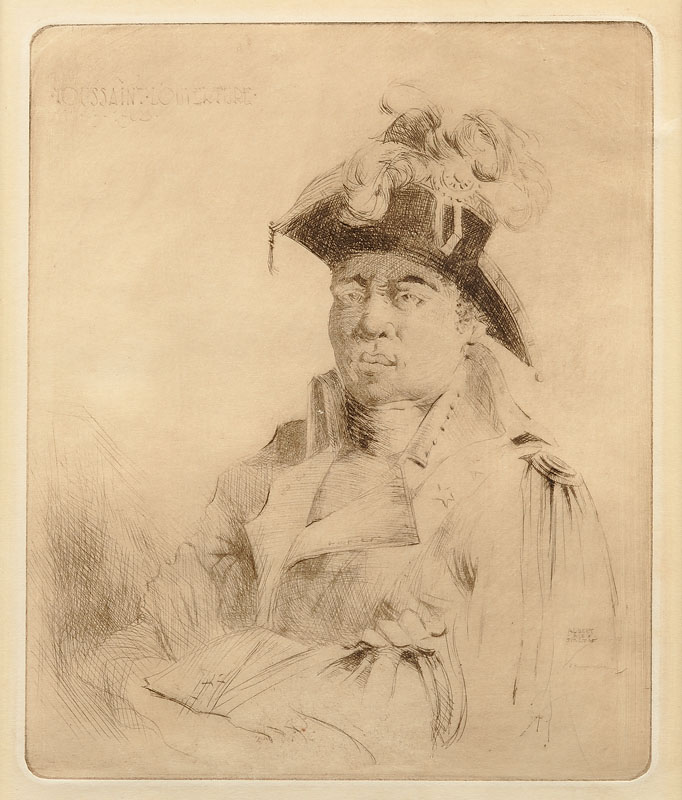

Toussaint L'Overture

Etching

9 3/4x8 1/8 inches

1922

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

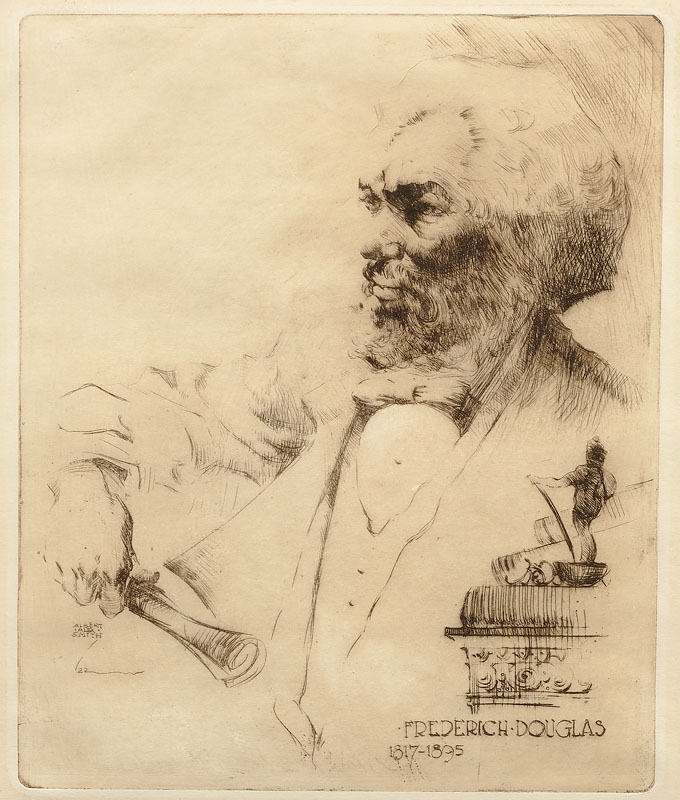

Frederick Douglas

Etching

9 5/8x7 7/8 inches

Year unknown

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

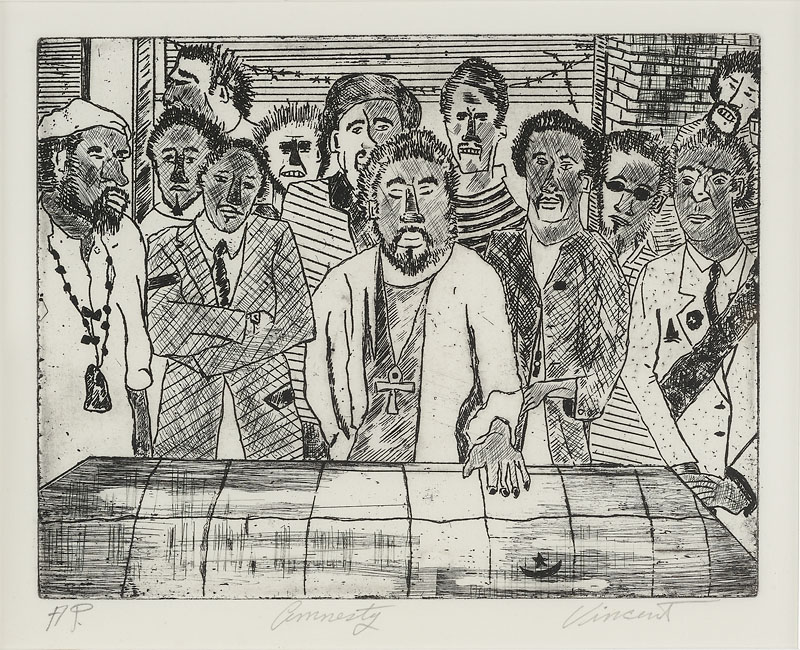

Vincent Smith (1929-2004)

Mr. Smith, who had more than 25 one-man shows and participated in more than 30 group exhibitions since the early 1970's, was among about a dozen prominent members of the Black Arts movement of the 1960's and 70's. A figurative painter with an often subtle, social thrust, he placed his subjects in a stylized way against geometric, textured and intricately colored backgrounds. He stood as an expressionistic bridge between the stark figures of Jacob Lawrence and the Cubist and Abstract strains represented by black artists like Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis.

Mr. Smith, a Brooklyn native, was a high school dropout who, family members said, spent his time in school sketching in his notebooks rather than listening to his teachers. He was a railroad and postal worker, traveled the country riding the rails as a hobo and served in the Army, all before beginning to work seriously as a painter in 1953.

He eventually returned to school to earn a college degree at 50. But it was his early bitter and sweet experiences as a black man that helped shape his work, along with several visits to Africa and a series of fellowships from Maine to Maryland.

The cumulative influence of these experiences were on view in his last show, this fall at the Alexandre Gallery in Manhattan.

In his review in The New York Times, Holland Cotter noted Mr. Smith's vibrant oranges and yellows, which he said glowed ''like light through stained glass.''

''The visual effect is a little reminiscent of Rouault's expressionism, but applied to a Social Realist art inflected with references to African culture,'' Mr. Cotter wrote.

Texture also played a role in Mr. Smith's work. He often used sand and pebbles mixed with paint, said Lowery Sims, executive director of the Studio Museum in Harlem. Mr. Smith also projected a political black nationalism and cultural nationalism that came out of the 60's and 70's, she said.

In 1999 the Metropolitan Museum of Art bought the first of three of his paintings, said Gil Einstein, his art dealer.

''He said that as a boy and a young man he went to the Met and never saw paintings that looked like himself or his life,'' Mr. Einstein said. ''This was important to him because it told how far he had come as an artist and as a representative of his people.''

Coming out of his Brownsville neighborhood in the mid-40's, Mr. Smith wandered the Bowery and Greenwich Village. His wife recalled that he was drawn to Manhattan as much by its romance as by his desire to escape the gangs and violence in his neighborhood.

Mr. Smith left his postal job to paint full time in 1953. He studied from 1954 to 1956 at the Brooklyn Museum Art School and later at the Skowhegan School of Painting in Maine. He was a recipient of a John Hay Whitney Fellowship in 1959 and in the 70's received travel fellowships to study and paint in Africa and Europe.

In interviews with the artist and art historian David C. Driskell, Mr. Smith talked of how his use of color and its luminosity followed his travels. After going from the grays and blacks of Brooklyn to the vibrant greens of Skowhegan, he began landscape paintings. In Africa the sunlight's yellows and oranges struck him and became more prominent in his work. ''It just seeps in,'' he said.

He also did illustrations for a line of greeting cards and for books on jazz and the blues by his friend Amiri Baraka, the poet. Manhattan subway riders using the West 116th Street station of the No. 2 line walk past two murals he made as part of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Art En Route program. More of his public art commissions are at social service centers in the Bronx and Harlem and at Boys and Girls High School in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn.

Partial Obituary from the NY Times. Link to full obituary:

http://www.nytimes.com/2004/01/03/arts/vincent-smith-74-painter-who-portrayed-black-life.html?mcubz=1

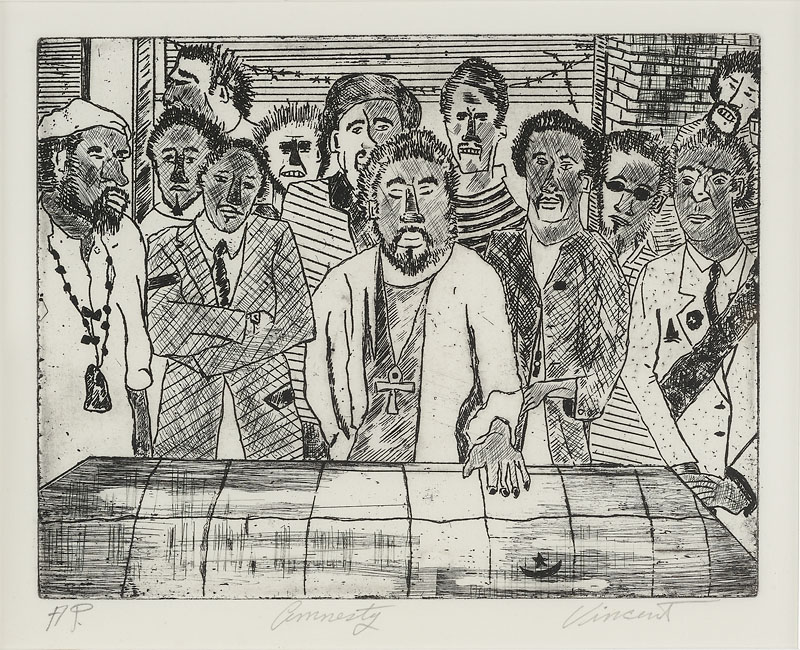

Amnesty

Etching

7x9 inches

Year unknown

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

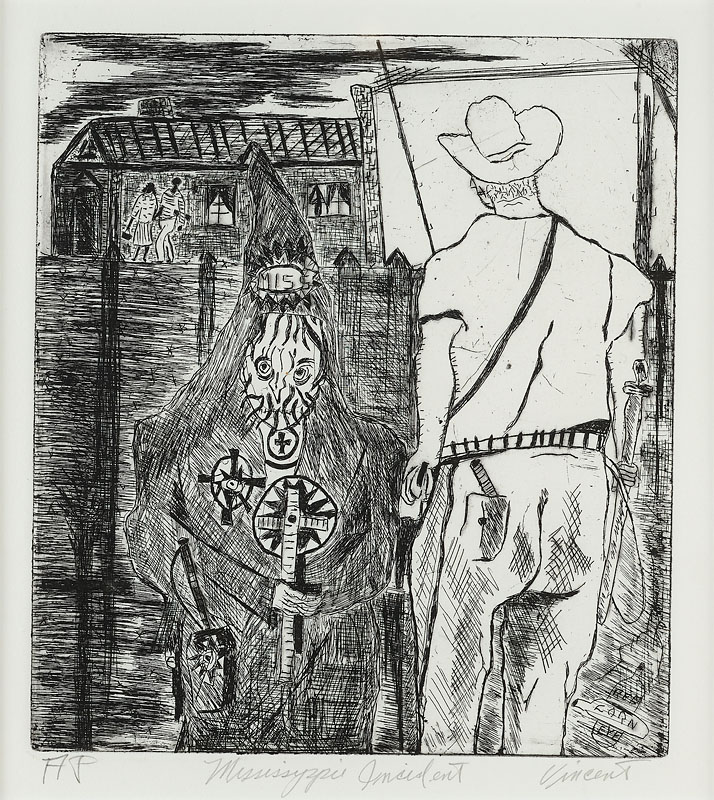

Mississippi Incident

Etching

9x8 Inches

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

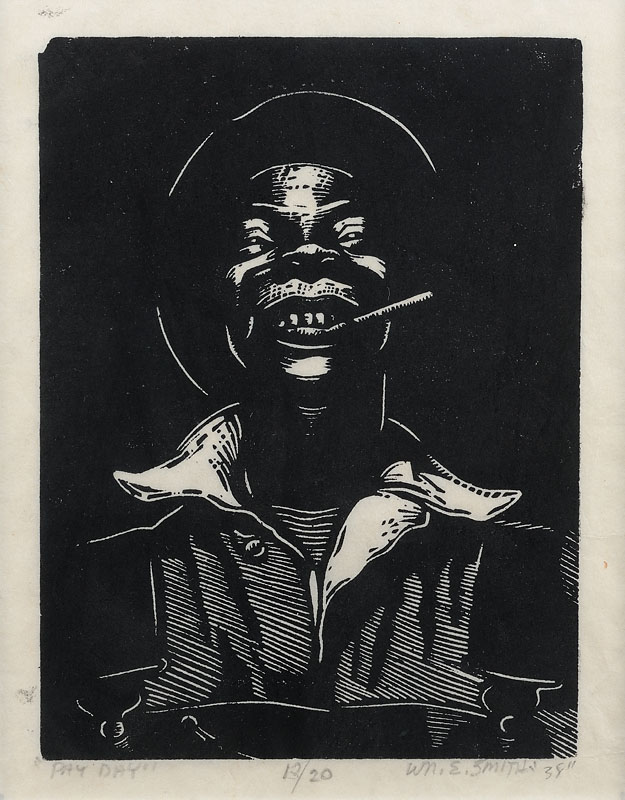

William E. Smith (1913-1997)

WILLIAM E. SMITH (1913-1997)

When William Elijah Smith was twelve, his mother died. His poor but supportive world in Chattanooga, Tennessee, ended and he traveled with his younger sister and brother to Cleveland to be with their father. In the early 1930s, still a teenager, having broken with his father, and living on his own in extreme hardship, Smith met Rowena and Russell Jelliffe, founders of Karamu House. They not only aided him financially but opened his world to the creative possibilities of their settlement house.

Originally known as the Playhouse Settlement, Karamu was then located at 38th Street and Central Avenue in Cleveland, and its philosophy stressed a commitment to excellence. In this inter-racial environment Smith, who was African American, worked with Marion Bonsteel, a graduate of the Cleveland Art Institute, and with Richard Beatty, who studied at the Carnegie Institute. Smith himself taught at Karamu until 1940. Karamu was well respected in Cleveland, especially for its strong performing arts programs that including theater, marionettes, and dance. At Karamu, Smith"s circle included Marjorie Witt Johnson. Her famous Karamu Dancers performed at the New York Worlds Fair in 1940, and she remained a support throughout his career.

It was at Karamu that Smith discovered printmaking and gained access to the brown battleship linoleum, from which he made linocuts. These prints are a highlight of his oeuvre and it is largely through them and their multiplicity that his work is known.

Smith showed at the Cleveland Artists Exhibitions at the Cleveland Museum of Art, in the 1930s and 40s. He was one of the Karamu Artists, Incorporated, along with Elmer W. Brown, Fred Carlo, Hughie Lee-Smith, Zell Ingram, Charles Sallee, Curtis Tann, Thomas Usher, and William Hulsinger. They participated in numerous Karamu exhibitions, including a major show at Associated American Artists, New York, that opened January 7, 1942, with Eleanor Roosevelt as the Honorary National Chairman.

From 1935 to 1940 Smith also attended the John Huntington Polytechnic Art Institute in Cleveland on a five-year Gilpin Scholarship named for the famous black actor, Charles Gilpin. During World War II Smith served in the United States Army, possibly with an all-black unit that participated in the famous Red Ball Express, a transportation and supply mission in France. In 1944, he won a trip to Paris in a GI art contest on the theme, How to Fight Mud as Well as Nazis.

After the War Smith attended the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art) where he studied with Paul Travis, and Hal Cooper"s School of Advertising. He moved to Los Angeles in around 1950. There he worked nights in the sign division of Lockheed Aircraft, attended the Chouinard Art Institute, 1956-60, and also taught classes in his studio for many years. He co-founded and exhibited with the Eleven Associated Artists" Gallery (originally the Black Artists" Gallery), in the 1950s; and in the Afro-American Art Exhibit (the Marian Matthews Collection), Los Angeles, 1969. Around this time his work was also featured at the Florenz Gallery, Hollywood.

Linocuts by Smith were included in Impressions/Expressions: Black American Graphics, the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, 1979/80, and the Gallery of Art, Howard University, Washington, DC, 1980, and Alone in a Crowd, Prints of the 1930s and 40s by African-American Artists from the Collection of Reba and Dave Williams. That show traveled to the Equitable Gallery, New York, and the Newark Museum of Art, New Jersey, 1992, the Long Beach Museum of Art, California, 1993, the New York State Museum, and Yale University Art Gallery, Hartford, Connecticut, 1994, and the Brooklyn Museum, New York, 1996. This collection is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Work by Smith was shown in The Russell and Rowena Jelliffe Collection: Prints & Drawings from the Karamu Workshop, 1929-1941, South Wing Gallery, St. Paul"s Episcopal Church, Cleveland Heights, 1991. In 1994 the exhibition was expanded to show the entire Jelliffe collection at the Cleveland State University Art Gallery, where it is now housed. Later in the 1990s the title of an exhibition, Yet Still We Rise, African American Art in Cleveland, 1920-1970, was a paraphrase taken from the Smith painting, ...And Yet I Still Rise, 1970. His watercolor, 38th and Central, 1942 (the location of Karamu House), was on the cover of the catalogue. The show traveled to Cleveland State University, 1996, the Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, and the Riffe Gallery, Columbus, 1997.

The exhibition, William E. Smith, Drawings and Linocuts, was on view at the Susan Teller Gallery, 2001. One-man shows of his work were also held at the Hull House, 1946, and Lyman Gallery, 1947, both in Chicago. The exhibition The Printmaker, From Umbrella Staves to Brush and Easel, was held at the Afro-American, Historical Society, Cleveland, 1976.

By far the largest archive of work by William E. Smith is found at the Cleveland State University Art Gallery where it is part of the Jelliffe Collection. Other the permanent collections with work by Smith are the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, the Syracuse University Art Gallery, NY, the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Oberlin College Art Museum, and the Gallery of Art, Howard University, and the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Bio courtesy of the Susan Teller Gallery. Link to bio: http://www.susantellergallery.com/cgi/STG_art.pl?artist=smith

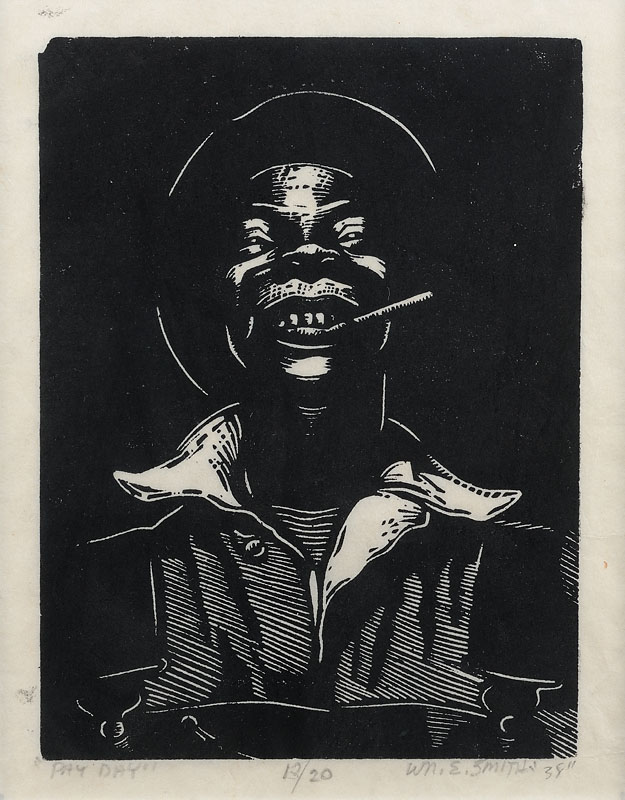

Pay Day

Linocut

8x6 inches

1938

Signed and dated

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

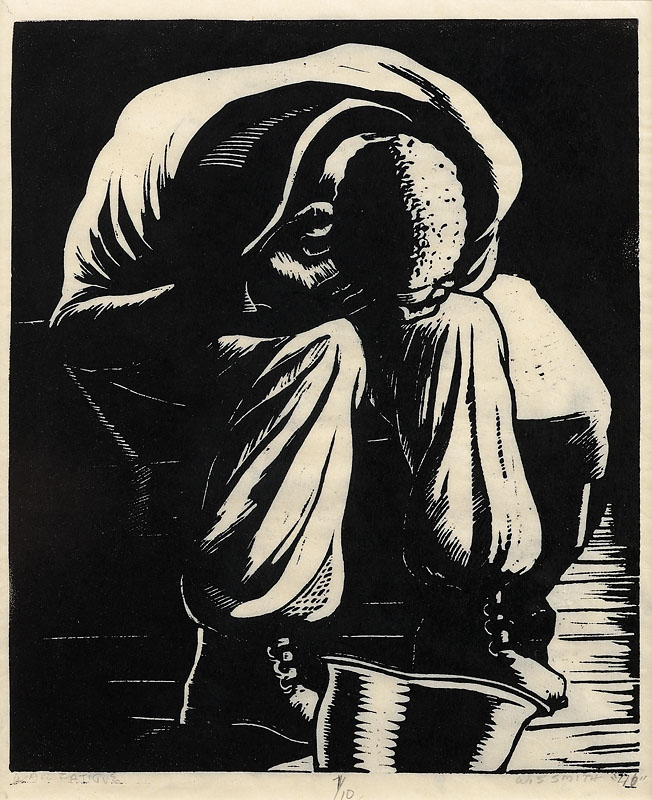

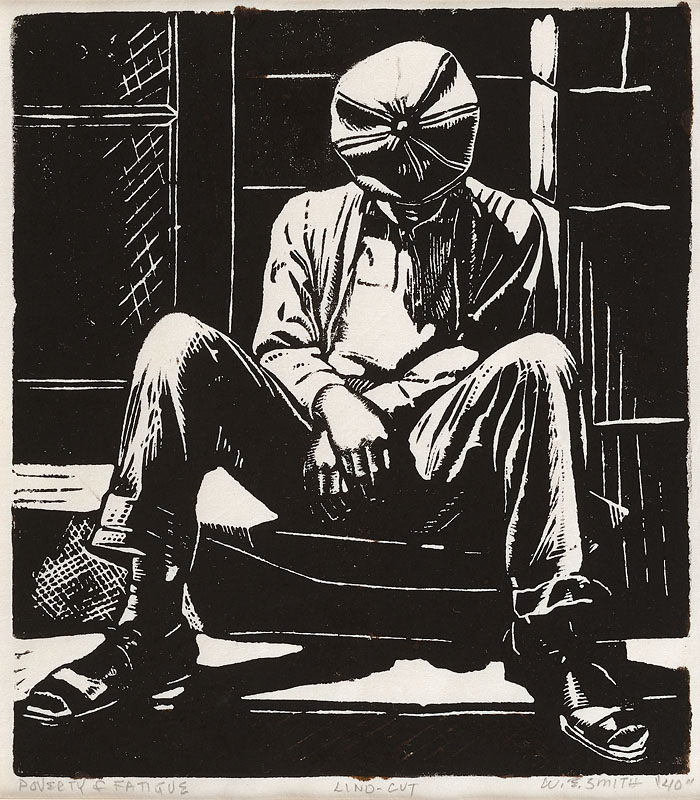

Poverty and Fatigue

Linocut

10 3/4x8 7/8 inches

1940

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

War Fatigue (American)

Linocut

9x8 inches

1940

Signed

Photo credit: John Wilson White Studio

Carroll Sockwell (1943-1992)

Born In 1943, Sockwell grew up in segregated Washington, the youngest son in a military family. Despite his family's relative prosperity, Sockwell led a troubled childhood and It was not until his artistic talents were recognized by Elinor Ulman, a noted art therapist and teacher at the Corcoran School of Art that Sockwell gained the confidence to pursue a career as an artist. At the age of seventeen he struck off for New York City where he immersed himself in the art scene of the time,meeting artists of the abstract expressionist movement and others beginning the expansion in Pop Art, Minimalism and conceptualism.

Upon his return to Washington in 1963. Sockwell found a city that itself had become an important art center. More than a place that housed great collections of art, it was a place that fostered a growing community of working artists from which the highly influential art critic Clement Greenberg had developed the Washington Color School. The Phillips Collection became a lodestone for Sockwell as he developed a deep appreciation for the Modernist works assembled there, especially Klee. Dove, and Braque. In a recent letter, Willem de Looper, former curator at the Phillips, commented that Sockwell, "knew the collection as well as I did -and I worked there."

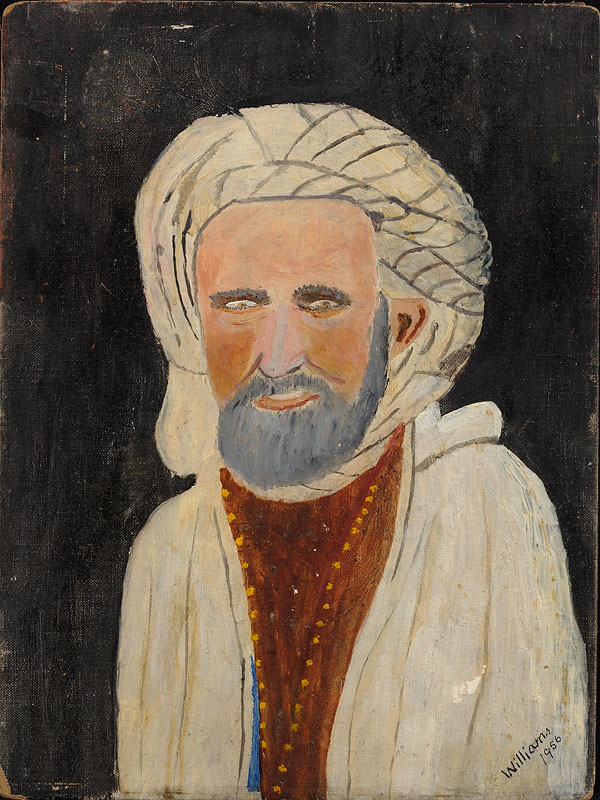

Sockwell then worked as a curator at the Barnett-Aden Gallery, the nation's first museum of African-American art, which was established in 1943 by James Herring and Alonzo Aden. He later exhibited at the Jefferson Place Gallery, then under the direction of Nesta Dorrance.